Failed Glory Satellite Launch Shouldn't Threaten NASA Deal, Rocket Builder Says

The launch failure that doomed NASA's Glory climate satellite shouldn't affect plans for the rocket's builder to fly cargo ships – and possibly even manned spacecraft – for NASA, the company said.

The Glory satellite launched early Friday (March 4) from California's Vandenberg Air Force Base at 2:09 a.m. PST (1009 GMT).

The satellite soared into the sky atop an expendable Taurus XL booster built by the Virginia-based aerospace company Orbital Sciences Corp., a company that also has a separate $1.9 billion deal with NASA to provide unmanned cargo delivery flights to the International Space Station using different rockets and spaceships.

The Glory liftoff went smoothly, but minutes later the rocket's nose-cone fairing – a shell-like covering that protects its satellite payload – failed to open as designed. The booster and the $424 million Glory apparently crashed into the Pacific Ocean, NASA said.

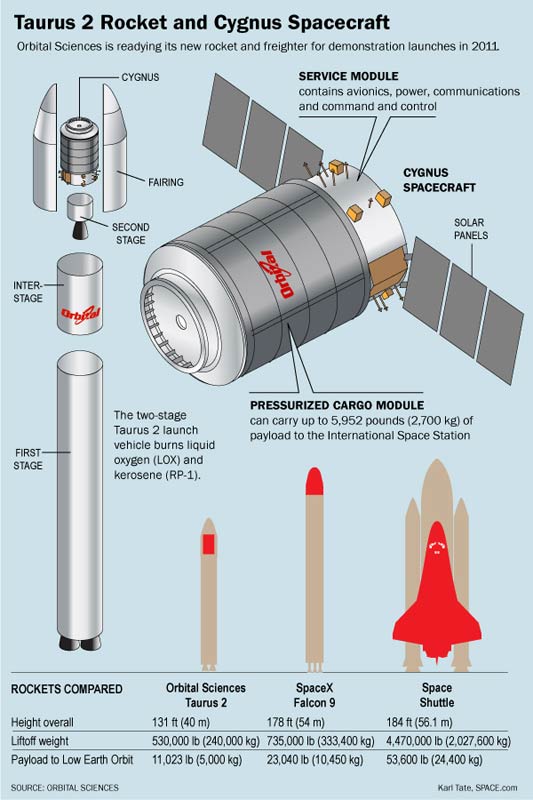

While it is still early after the incident, Orbital Sciences officials don't anticipate serious fallout from the Taurus XL launch failure to affect its separate Taurus 2 rocket and Cygnus spaceship program. Those new vehicles are the ones picked by NASA to help keep space station crews stocked with supplies after the agency retires its shuttle fleet later this year.

A devastating blow

Still, the Glory launch failure has been a shock.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The whole extended team, the satellite folks at NASA who have worked so hard over the years on this, and of course our Taurus team, is pretty devastated by this," said Orbital Sciences spokesman Barron Beneski. "It's a tough day." [Video of NASA's Failed Glory Satellite Launch]

It's the second launch failure for a NASA climate satellite atop an Orbital rocket. In 2009, a Taurus rocket carrying NASA's Orbiting Carbon Observatory also fell into the ocean after its fairing failed to open.

Following that mishap, NASA and Orbital investigated the issue and thought they had fixed the problem. In the intervening years, Orbital has flown other similar rockets with the same fairing technology without problems.

"What the two mission failures have in common was that the fairing didn't come off," Beneski told SPACE.com. "Why the fairing didn’t come off could be completely different. That's to be determined."

Track record of success

Despite today's loss, the Dulles, Va.-based company said it has a strong record overall.

"Between the time of the OCO failure and early this morning, Orbital had launched 20 rockets for a variety of customers, and many of those rockets shared some similar characteristics [with the Taurus that failed today]," Beneski said. "But from time to time, a seemingly small thing can come up. You think you've done everything humanly possible, and I know our team including the Orbital Taurus team, they scrubbed that rocket from stem to stern." [NASA's Lost Glory Satellite: Why It Failed and Why It Matters]

Ultimately, rocket science is still a risky, finicky, complicated business, he said.

Orbital is one of two companies – the other is Space Exploration Technologies (SpaceX) – to hold a contract to build and fly unmanned cargo ships to resupply the International Space Station after NASA's space shuttles retire this year.

Orbital is still developing the new Taurus 2 rocket and robotic Cygnus space capsule to carry out this job. Under its $1.9 billion deal with NASA, Orbital will provide eight Cygnus flights to deliver cargo to the station through about 2016.

The first Taurus 2 rocket is scheduled to make its first test flight, with a dummy Cygnus vehicle, later this year.

Orbital Sciences is also one of eight companies on NASA's short list of contenders to build a commercial spaceship that can carry astronauts to low-Earth orbit and the space station after the shuttles are gone.

NASA chief Charlie Bolden recently expressed confidence in Orbital's ability to deliver these services based on the company's solid record, when he spoke Wednesday at a hearing of the House Committee on Science, Space and Technology.

"Orbital is one of our competitors right now in [the cargo delivery project], and they announced they intend to compete in commercial crew," Bolden said two days before the Glory accident. "They’ve launched 155 successful space launches. Many of my satellites on orbit today were put there by Orbital."

Despite today's setback, Beneski said he does not expect the accident to hinder Orbital's chances in the cargo or crew spaceship competitions.

"We've been in business for almost 30 years," he said. "We've launched hundreds of rockets and built hundreds of satellites. We have one of the better records for liability in the world when you combine all of our space systems together. But when you do it as long as we've done it, and when you're as active, with as many launches and satellite deployments, it's very difficult to keep a hundred percent winning streak."

And Orbital's proposal to fly a crew capsule for NASA would not use one of the company's rockets at all, at least initially.

Instead, Orbital plans to launch its spaceship – a winged space plane called Prometheus – atop an Atlas 5 rocket built by the United Launch Alliance, a joint launch-providing venture by aerospace giants Lockheed Martin and Boeing. That booster so far does have a near-perfect track record of more than 20 successful launches.

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.