For astronauts living on the International Space Station, getting sick or injured can be a big deal — they're zooming around the Earth at 17,500 mph (28,163 kph), far beyond the reach of hospitals on the ground.

The space station is also not outfitted with a full suite of medical diagnostic equipment, so getting to the bottom of mystery pains and ailments isn't as simple as it can be here on terra firma. Bulky imaging devices like X-ray machines and MRI scanners are so large and heavy that they're just not cost-effective to launch into space.

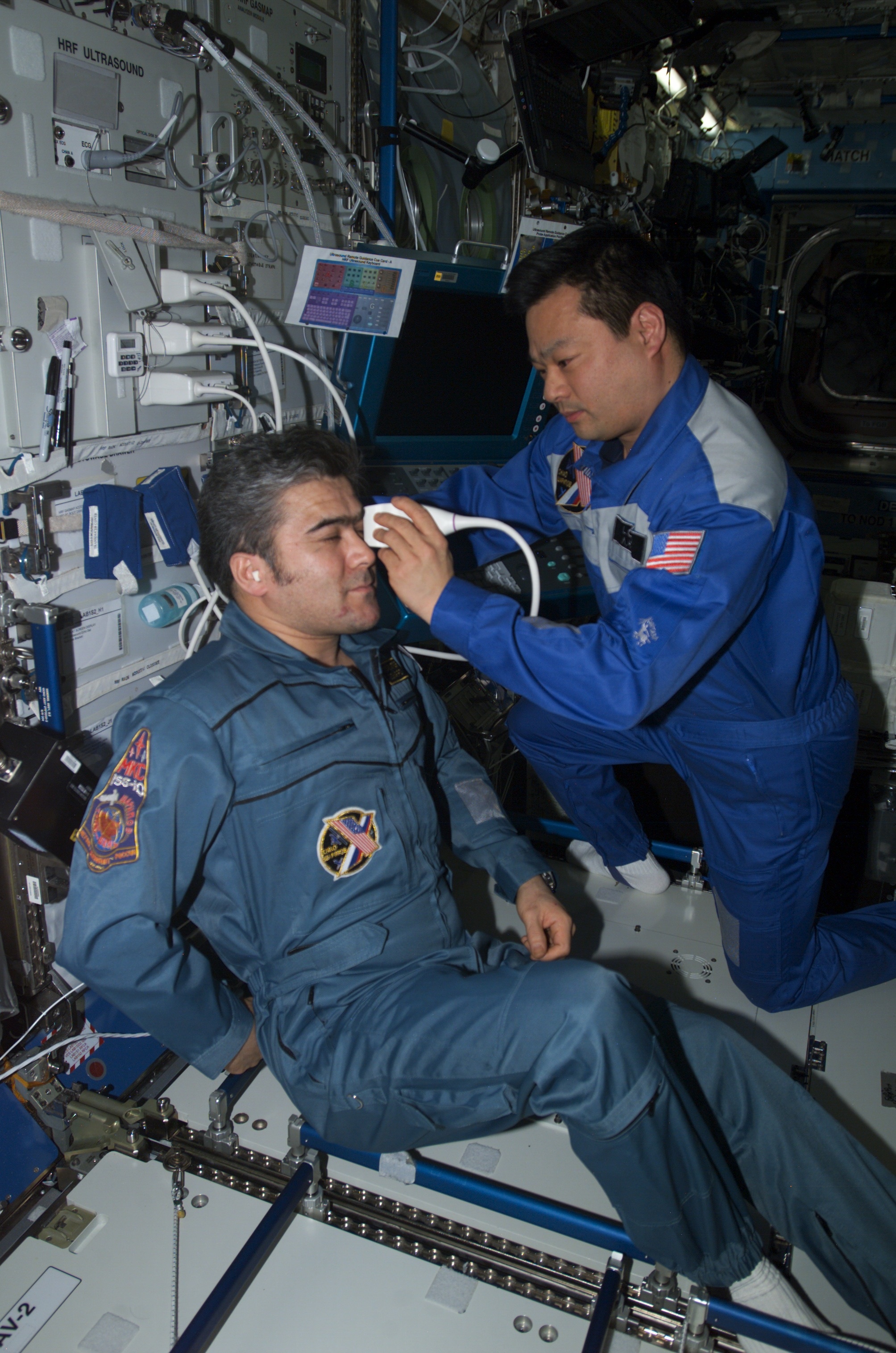

But as in many areas, spaceflyers have gotten creative, working well with the limited options at their disposal. NASA helped turn the station's ultrasound machine, for example, into an all-purpose diagnostic imager with a direct line to doctors on Earth.

The technology helps keep astronauts healthy, and it holds great promise for diagnosing sickness in isolated people and communities around the world, from mountaineers climbing Everest to villagers in Bolivia.

Ultrasound: diagnosis at a distance

Ultrasound machines emit high-frequency sound waves that bounce back at points of differing density —for instance, the boundary between soft tissue and bone. The devices reconstruct these sonic echoes into two- or three-dimensional images.

On Earth, ultrasound is commonly used to image fetus development and to look at blood flow in people with cardiovascular problems. Diagnosing other issues, such as broken bones and collapsed lungs, are primarly the province of X-ray and MRI machines, NASA officials said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But since the orbiting lab doesn't have X-ray and MRI machines — and does have ultrasound gear — NASA hoped ultrasound's reach could be extended a bit. So in 2000, the agency's Johnson Space Center initiated a collaboration with Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit and Wyle Laboratories in Houston to devise a more general-purpose ultrasound technique.

The research team developed non-conventional ultrasound methods that allowed them to image a wider variety of body parts — and, as a result, diagnose a broader range of ailments.

For example, the novel techniques can evaluate tooth or sinus infections, researchers said. And the methods can also gauge the effects of spaceflight on astronauts' central nervous systems, by measuring changes in the diameter of the eye's optic nerve sheath.

Ultrasound images taken on the space station are beamed down to Earth via satellite downlink. The pictures are high-resolution and high-quality, allowing doctors to spot problems and make diagnoses.

Bringing the technology down to Earth

Researchers soon recognized that remote-diagnosis ultrasound isn't necessarily just for astronauts — the technique holds great promise for regular Earthbound folks as well. So they began working to develop a terra firma version that could be used by everyone.

Perhaps the biggest obstacle, researchers said, was finding a cost-effective way to transmit diagnosis-quality images from a farflung patient to a doctor — without the benefit of access to NASA's satellite hookups and huge telemedical network.

So researchers at Wyle and Henry Ford Hospital began working with a computer-imaging company called Epiphan Systems. The result was the formation of Mediphan, a company that specializes in remote medical diagnostics technology, NASA officials said.

Drawing partly on some NASA expertise, Mediphan came up with two devices: one that stores and archives high-quality ultrasound images, and another that transmits them securely over the Internet, with almost no loss of quality.

The instruments have already been put to widespread use.

Major professional sports teams in the United States use them to quickly diagnose injuries that happen in practices and games, NASA officials said. And remote-diagnosis ultrasound has been helping keep Olympic athletes healthy since the 2006 Winter Games in Torino, Italy.

Researchers are also working to expand the technology's reach to all corners of the globe, officials said. Someday soon, doctors in London or Boston could be using it to diagnose the illnesses of villagers in the rain forests of Laos or the deserts of Botswana.

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.