The Moon Visits Two Star Clusters in Night Sky

Over the next few days, the moon will move past two of the prettiest star clusters in the sky.

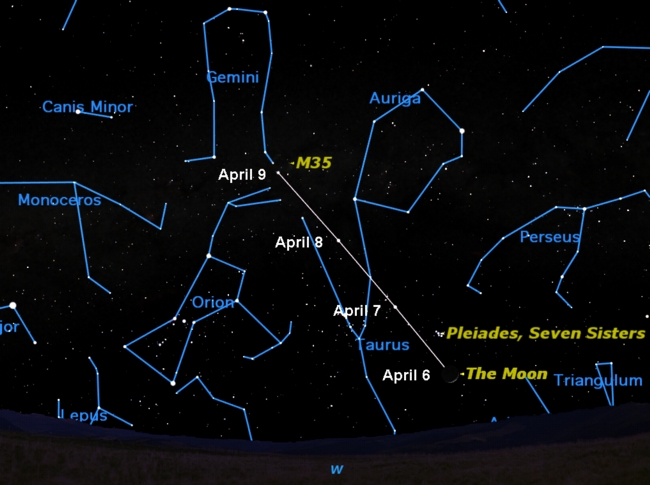

Tonight (April 6) the moon will be located just below the brightest star cluster we can see from Earth — the Pleiades, which is found in the constellation Taurus. By Saturday, the moon will nearing another nice cluster, known as Messier 35.

The Pleiades cluster has been known since antiquity by nearly every culture around the world. It is best known as the Pleiades or the Seven Sisters, even though only six of its stars are readily visible with the naked eye.

This sky map of the moon and star clusters shows how they will appear together this week.

Not the Little Dipper

Beginning stargazersoften mistake the Pleiades for the Little Dipper, because it is dipper-shaped and much brighter than the real Little Dipper. In Japanese, the cluster is known as Subaru, and the Japanese automakeruses a picture of the Pleiades as its logo. In Australia, the Pleiades are known as “the Shopping Cart.”

Tonight, the Pleiades are easily seen just above the thin waxing crescent moon. By Thursday, the moon will have moved so that it is above and to the left of the Pleiades. The cluster will be readily visible with the naked eye on both nights, though it looks even better in binoculars or a small telescope. With either of those vision aids, hundreds of stars in this cluster become visible.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

By Saturday night (April 9) the moon will have moved on from Taurus into Gemini, and it will be near another fine cluster. This one has no name, only a number in the famous catalog compiled by Charles Messier: Messier 35 (or M35 for short).

Charles Messier was an eminent hunter of comets in the 18th century. To make identification of comets easier, he compiled a list of permanent objects in the sky that look somewhat like comets. His list contains 110 objects that represent the brightest and best deep-sky objects in the heavens: star clusters, nebulae and galaxies.

Observing his list has become a popular project for amateur astronomers, who attempt to spot all 110 objects Messier saw. In the process, they learn what deep-sky objects look like, and how to find their way around the sky.

Messier 35

Messier first observed the M35 cluster on August 30, 1764. This cluster has many more stars than the Pleiades, but is seven times farther away from us — 2,850 light-years as opposed to 410 light-years for the Pleiades. In binoculars it just appears as a dim glow; it takes a small telescope to resolve it into stars.

The Pleiades are also in Messier’s catalog as Messier 45, but he did not discover that cluster. When he was about to publish his catalog for the first time, Mesier added a few well-known objects to pad its numbers up to 45, including the Orion Nebula (Messier 42 and 43), the Beehive Cluster (Messier 44) and the Pleiades (Messier 45).

Some years later, Messier published a larger catalog of 103 objects, and noted in his personal copy six more, bringing the total to 109. In recent years, astronomers have added a last object to bring the total to an even 110 objects. This last object is one of the two satellite galaxies of the Andromeda Galaxy (Messier 31), which Messier observed and drew, but never assigned a number.

This article was provided to SPACE.com by Starry Night Education, the leader in space science curriculum solutions.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Geoff Gaherty was Space.com's Night Sky columnist and in partnership with Starry Night software and a dedicated amateur astronomer who sought to share the wonders of the night sky with the world. Based in Canada, Geoff studied mathematics and physics at McGill University and earned a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Toronto, all while pursuing a passion for the night sky and serving as an astronomy communicator. He credited a partial solar eclipse observed in 1946 (at age 5) and his 1957 sighting of the Comet Arend-Roland as a teenager for sparking his interest in amateur astronomy. In 2008, Geoff won the Chant Medal from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, an award given to a Canadian amateur astronomer in recognition of their lifetime achievements. Sadly, Geoff passed away July 7, 2016 due to complications from a kidney transplant, but his legacy continues at Starry Night.