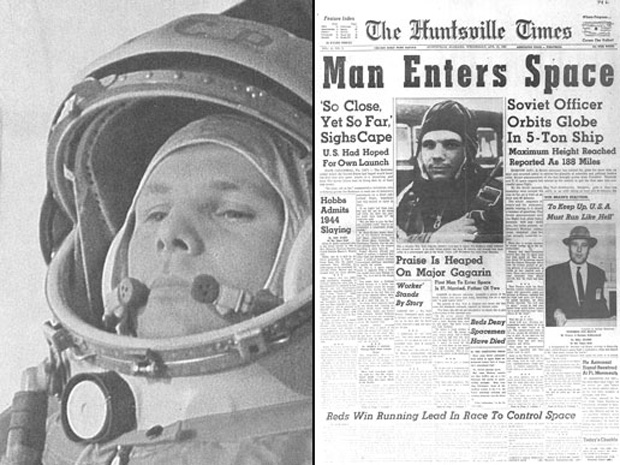

Fifty years ago, cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first person in space, giving the Soviet Union a huge victory in its Cold War space race against the United States. But experts say it didn't have to happen that way.

American astronaut Alan Shepard probably could have reached space before April 12, 1961, when Gagarin launched into orbit . Similarly, the United States likely could have put a satellite into Earth orbit before the Soviets, whose October 1957 launch of Sputnik 1 shocked America and set the space race in motion.

Some key decisions conspired against such a chain of events. The result: American technological pride took a serious beating twice in four years.

But as it turned out, the two stunning defeats didn't demoralize the United States. Rather, they lit a fire under the American space program, paving the way for its crowning achievement — putting a man on the moon in 1969. [Giant Leaps: Top Milestones of Human Spaceflight]

"In some ways, Sputnik and Gagarin were like gifts to NASA," said noted space historian Asif Siddiqi of Fordham University, who has written several books about the Soviet space program and the space race. "You're not going to have a moon program without that kind of a shock."

"Alan's Night"?

April 12 is known around the world as "Yuri's Night," to celebrate the cosmonaut and his historic achievement. But if the United States had been a little less cautious, every March might see a celebration of "Alan's Night" instead. [Video: Yuri Gagarin: First Man in Space]

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In the winter and spring of 1961, NASA's Project Mercury — the nation's first human spaceflight program — was gearing up to send Shepard on a suborbital jaunt. And NASA had made a lot of progress by March.

"Certainly that launch could've happened before April 12," Siddiqi told SPACE.com. "There's no reason it couldn't have happened. Everything was ready."

But late in the game, NASA decided to insert one more test flight into the schedule. Some problems with the Mercury-Redstone rocket for Shepard's mission had emerged on previous test flights, and the team — including chief rocket designer Wernher von Braun — wanted to make sure all the kinks were worked out before they risked a human life.

"Von Braun was by nature a very conservative person, and I think he felt like it wasn't just right yet to launch Shepard," Siddiqi said. "So he decided to have one more test."

That test took place March 24, 1961, pushing Shepard's flight back. U.S. officials apparently didn't know the Soviets were going to launch Gagarin less than three weeks later. Had they known, perhaps they would have had more of a sense of urgency. [Top 10 Soviet and Russian Space Missions]

"There were indications that the Soviet Union was ramping up to a manned flight," said space history expert Robert Pearlman, editor of the website collectSPACE.com, which is a SPACE.com partner. "But we didn't know exactly when the launch would be."

A different kind of accomplishment

Shepard ended up blasting off in his Freedom 7 vehicle on May 5, 1961, less than a month after Gagarin.

The Freedom 7's flight reached suborbital space, lasting just 15 minutes before splashing down in the Atlantic Ocean 302 miles (486 kilometers) from the Florida launch site. Gagarin, by contrast, had orbited Earth once before landing safely 108 minutes later. [Infographic: How the First Human Spaceflight Worked]

The U.S. wouldn't duplicate Gagarin's feat for nearly a year, until John Glenn's orbital flight in February 1962. So even if Shepard had beaten Gagarin into space, the Soviets would still have claimed some measure of victory.

"Gagarin made it into orbit, so that's a very different kind of achievement," Siddiqi said. "And NASA wasn't really ready to do that until early '62. There's no way they could've launched somebody to orbit in early '61."

No Sputnik moment?

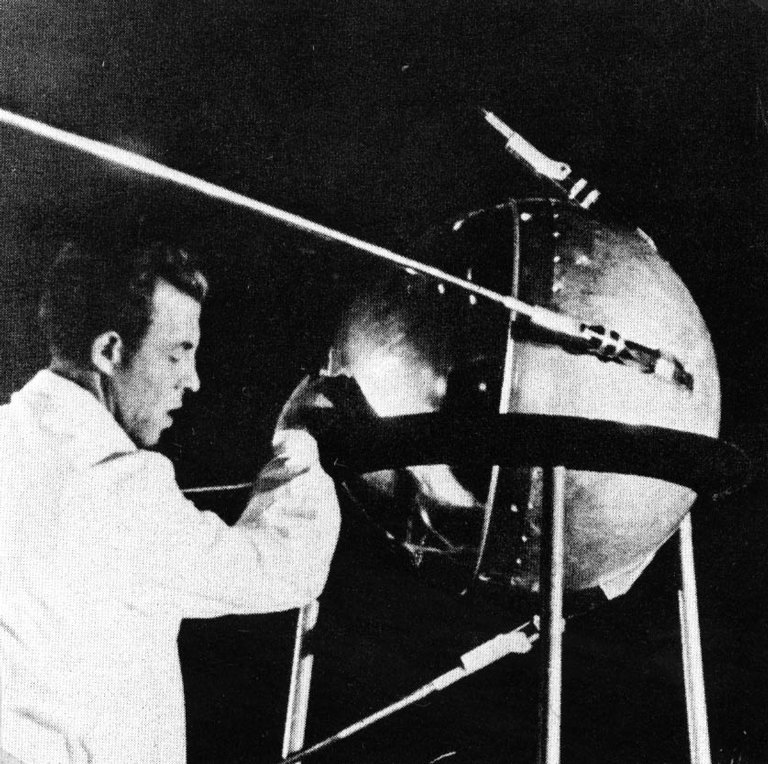

The Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1 — the world's first artificial satellite — on Oct. 4, 1957. The event sent shockwaves around the globe. They hit hardest in the United States. [Biggest Revelations of the Space Age]

"A lot of people at the time called Sputnik a technological Pearl Harbor," Siddiqi said. "It was a big blow against American prestige."

The U.S. probably had the know-how to put a satellite up before Sputnik, however — and might have done so, had the nation's top brass made a few different decisions along the way.

Von Braun had been working hard to develop a line of launch vehicles based on Jupiter missiles, and by 1956 his team was close to building a rocket that could carry a satellite to space. But the U.S. government chose to focus most of its official funding on a different rocket-and-satellite project, called Vanguard, instead.

Vanguard wasn't ready to launch by the autumn of 1957, when Sputnik soared into the heavens. Von Braun's effort probably would've been good to go, had it been given the proper attention and funding, Siddiqi said.

"If there had been a commitment in '56, von Braun probably could've done it by early '57," Siddiqi said. "But there was none."

Misjudging a satellite's impact

Before Sputnik, the United States was not really racing into space. Government officials and scientists were apparently more focused on putting something useful into orbit than on getting there first.

"Sputnik was basically a hunk of metal," Siddiqi said. "I think most people didn't realize that launching a satellite would be that big a deal."

It was a big deal, though — so much so that any event that now forces America to question and then attempt to reassert its technical dominance is known as a "Sputnik moment."

After the successful launch of Sputnik 1 — and then Sputnik 2 just a month later — the U.S. scrambled to show its satellite stuff. But the Vanguard TV3 satellite mission got just 4 feet off the pad in December 1957 before exploding, a humiliating failure observers at the time branded "Flopnik" and "Kaputnik."

In the end, von Braun came through, albeit too late to salvage American pride. The Jupiter C (also known as Juno I) rocket built by his team carried the Explorer 1 satellite into space on Jan. 31, 1958.

Spurring Apollo

Sputnik and Gagarin were tough pills for Americans to swallow. But without those two stinging defeats, the United States probably wouldn't have landed human beings on the moon before the close of the 1960s, experts say.

Shortly after Gagarin's successful flight, President John F. Kennedy met with some of his top advisers.

"Kennedy asked them, 'What can we do to beat these guys?'" Siddiqi said. "They conferred for a few weeks, and they came up with the moon landing."

The U.S. had envisioned putting a space station into Earth orbit and developing a space shuttle before pushing for the moon, Pearlman said. But after Gagarin, landing a human on the moon took precedence — partly because it would be tough for the Soviets to top.

"The next step above that is, foreseeably, Mars. And that would be considerably harder, and much less likely to be pursued by the Soviets, than simply putting a space station in orbit," Pearlman told SPACE.com.

The resulting Apollo program was a full-on rush to the moon. And it all came to fruition on the evening on July 20, 1969, when Neil Armstrong's boot clomped down into the lunar dust.

By the end of Apollo in 1972, the U.S. had spent about $25 billion on the program, Siddiqi said — well over $100 billion in today's dollars.

The moon landing was an incredible achievement for the entire human race. And it almost certainly wouldn't have happened so quickly if not for those big Soviet victories a decade or so earlier.

"People romanticize Apollo as this golden era, and for sure it was," Siddiqi said. "But it only happened because of the Soviets."

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.