Is Space Tourism the New Space Race?

Fifty years after the Soviet Union beat the United States to send the first human to space, a new space race is heating up.

This time, the players are not nations — rather, they're commercial companies that aim to send the first paying passengers to space on private spaceships.

"It's an exciting time for the industry," said George Whitesides, president of suborbital spaceship company Virgin Galactic. "I really believe that we're at the edge of an extraordinary period of innovation which will radically change our world."

If Virgin and other companies succeed, space could soon become one more conquered frontier, with rocket rides to space becoming as accessible as plane rides across the Atlantic.

"We're just about to the point where low-Earth orbit really ought to be considered part of our normal regime," said Roger Launius, a space history curator at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. [Infographic: Spaceships of the World]

But while we may be nearing a tipping point where access to space expands widely beyond the select few who've left Earth to date, Launius and others caution that it's not a done deal yet.

Suborbital joyrides

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The first person to reach space, Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin, made his flight almost 50 years ago, on April 12, 1961.

Since then, the rest of us have been waiting our turn. Now the day when we can all take a space vacation is closer than ever, with a handful of commercial firms planning to offer quick suborbital joyrides in the next few years.

Suborbital spaceships would take passengers up to space at an altitude of about 62 miles (100 kilometers), but wouldn't complete a full orbit before returning to Earth. Instead, riders would see the globe of our planet and the blackness of space while experiencing about five minutes of weightlessness, and then land back down just hours after they took off. [First Person: How I Trained For Suborbital Spaceflight]

One of the most prominent suborbital space companies is Virgin Galactic, founded by British billionaire Sir Richard Branson. Virgin Galactic's suborbital spaceplane is called SpaceShipTwo. It's designed to be carried to midair by a giant mothership, named WhiteKnightTwo, and then to drop and fire its own rocket engine for the last climb to space.

SpaceShipTwo has made a few successful test glide flights, with the first powered flights — in which the space plane's rocket engines will fire — set to occur sometime this year.

Branson and his family are slated to be the spacecraft's first passengers, with regular tourist flights beginning in 2012, Virgin Galactic officials have said.

"I think the whole world will be watching those flights," Whitesides told SPACE.com. "To a certain extent, it will really kick off the second space age. The idea that space is truly opening to the rest of us will become real in a very concrete way with those."

Other contenders

Virgin Galactic is not alone. A handful of other companies are also racing to build suborbital vehicles to meet the perceived demand from tourists, as well as scientists who'd like to conduct short experiments in microgravity.

The secretive Blue Origins company, bankrolled by Amazon.com founder Jeff Bezos, is developing the suborbital Goddard vehicle under the firm's New Shepard program.

Armadillo Aerospace, a Texas-based company founded by computer game entrepreneur John Carmack, is another contender with a vertically launched rocket ship in development.

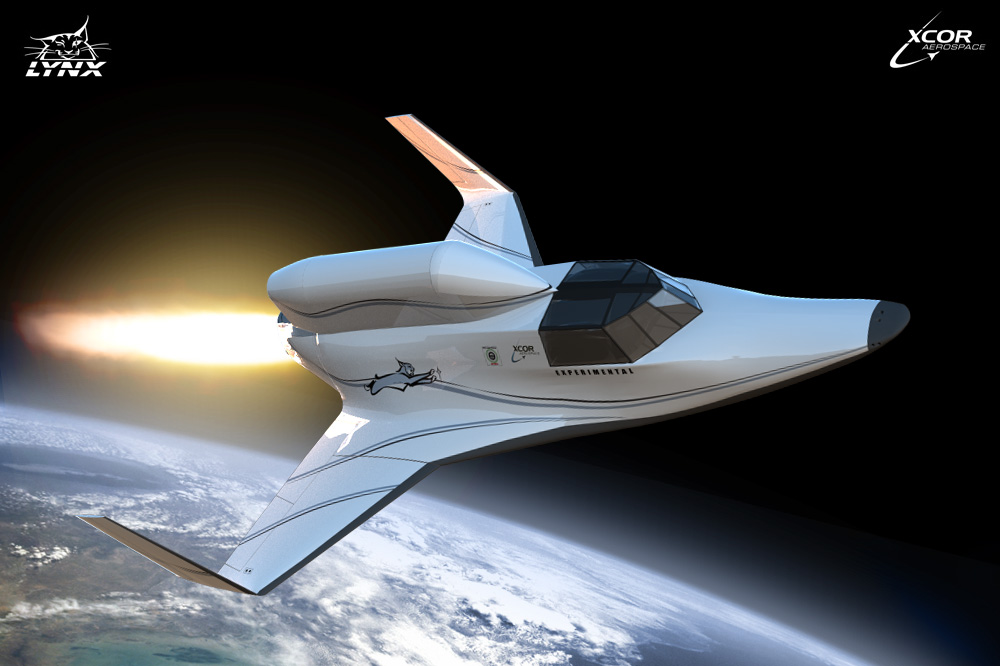

Masten Space Systems, and XCOR Aerospace, both of Mojave, Calif., are also building suborbital spaceships called Xaero and Lynx, respectively.

However, even when suborbital passenger flights do begin to take off, they won't come cheap.

Tickets on SpaceShipTwo are priced at $200,000 per seat to start, which doesn't exactly make such trips accessible to everyday folks. Nonetheless, more than 380 customers have already put down deposits for their flights, with many more on the waiting list.

At $102,000 a pop, Armadillo Aerospace's flights will be a relative bargain. And as more suborbital flights take place in the future, the prices for all of them will come down, officials from numerous companies have said.

Orbital trips

Another frontier for the new space race is orbital spaceflight. These trips, which would require a rocket to go high and fast enough to reach Earth orbit, are significantly tougher than suborbital trips, but could potentially offer more payoffs, such as extended stays at the International Space Station or maybe even the space hotel being developed by Las Vegas-based firm Bigelow Aerospace.

A number of commercial space companies are vying to provide such a service to paying passengers, as well as to NASA, which will be in the market for new transportation to low-Earth orbit after its three space shuttles retire this year. [10 Private Spaceships Headed for Reality]

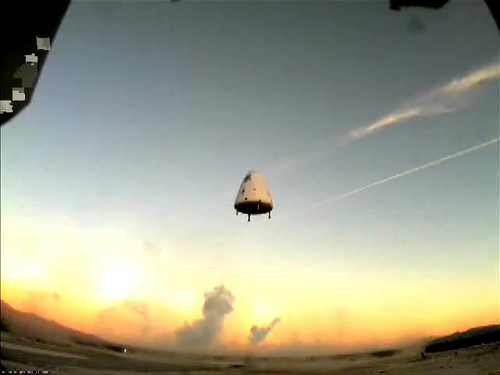

A leader here is Hawthorne, Calif.-based Space Exploration Technologies (SpaceX), which in October 2010 became the first private company to launch a space capsule to orbit and then recover it after landing.

"SpaceX achieved a very remarkable success," said former NASA astronaut Garrett Reisman, who quit the space agency in March to join SpaceX as a senior engineer. "The booster performed very well and the spacecraft performed great. It orbited twice and splashed down within a mile of the designated target on the first try."

SpaceX has so far conducted only that one test flight of its Dragon vehicle, which flies atop the company's Falcon 9 rocket. But the test went off without a hitch, and the company hopes soon to convert the Dragon, currently outfitted to carry cargo, into a man-rated capsule capable of ferrying humans.

Others vying in the orbital space race include Sparks, Nev.-based Sierra Nevada, with the Dream Chaser spaceship, Orbital Sciences of Dulles, Va., with its Cygnus spacecraft, Chicago-based PlanetSpace, Inc., with its Silver Dart space plane, and Excalibur Almaz Limited, based in the Isle of Man, which is retrofitting old Soviet spaceships for new flights.

Getting close

While we may be closer than ever to a new commercial space age, enthusiasm should be tempered with caution, Launius said, warning that this isn't the first time private companies have aimed to take over space.

"We've had these kinds of cycles in the past," Launius said. "In the 1990s, there was a whole series of these entrepreneurial firms that emerged that were going to try to do all these kinds of things. But they were never able to satisfy what they intended to satisfy."

Launius pointed to firms such as Rocketplane Kistler, which aimed to build a reusable orbital spacecraft to service the International Space Station, but went bankrupt in 2010, and Space Services, Inc., which developed the Conestoga rocket, but gave up on the vehicle after a Conestoga 1620 rocket exploded after liftoff in 1995. Many other failed rockets have taken similar paths over the years.

Time will tell if this time it works.

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.