Icy Moon Creates Extra Northern Lights on Saturn

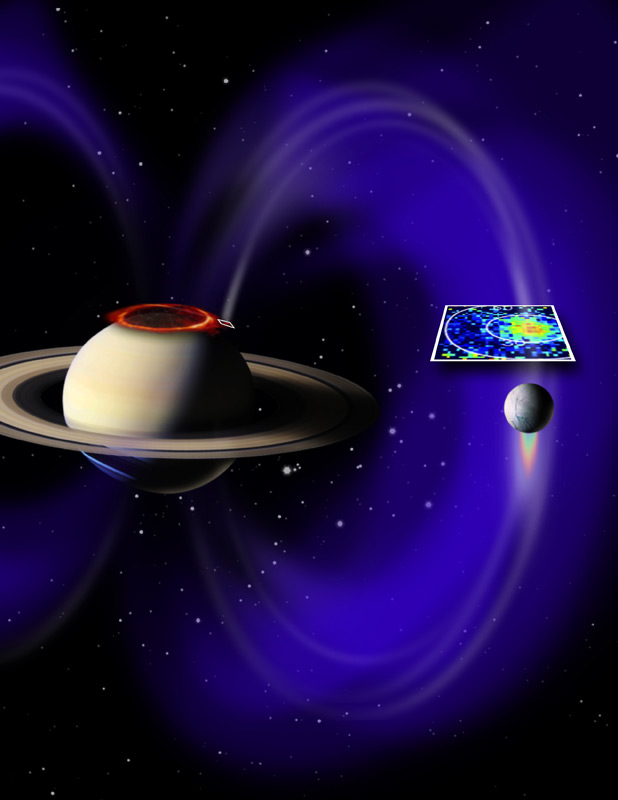

A shimmering patch of light as big as Sweden detected at the north pole of Saturn is the spectacular result of a giant stream of electrically charged particles from the planet's moon Enceladus, scientists find.

On Earth, surges of charged particles from the sun colliding with our planet's magnetic field create the northern and southern lights, or auroras. Similar patches of light have been seen on Jupiter, caused by electrons and ions originating from that planet's volcanically active moon Io.

Saturn also has its own aurora light show, which is created when solar particles from the sun interact with the planet's magnetic field. The new study, however, is the first time astronomers have caught a Saturn moon creating auroras on the ringed planet.

Enceladus is an extraordinarily active moon, with "ice volcanoes" (cryovolcanoes) that spray water vapor and organic particles into space. Researchers had long suspected that would cause aurora-like spots on Saturn. However, space telescopes gazing at the ringed planet failed for years to find any evidence of such patches. [Video: Saturn's Spectacular Aurora]

Now, using NASA's Cassini spacecraft in orbit around Saturn, researchers have finally detected signs of these lights.

The eruptions on Enceladus create a massive cloud of electrically charged plasma that shoots electrons and ions 150,000 miles (240,000 kilometers) along magnetic field lines to blast Saturn's north pole. The resulting spot of light measures about 750 miles (1,200 kilometers) by about 250 miles (400 kilometers), covering an area slightly larger than California. Scientists compared it to Sweden.

At its brightest, the patch shines with an ultraviolet light far less intense than Saturn's polar aurora but comparable to the faintest Earth aurora visible without a telescope. [Photos: Saturn's Rings and Moons]

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The scientists note this patch appears to vary in brightness by up to a factor of three, suggesting Enceladus spews out matter at a very non-constant rate.

"The electron beams flicker with timescales on the order of minutes," said researcher Abigail Rymer, a Cassini team scientist based at Johns Hopkins University. "It is a very dynamic interaction."

Although it remains unclear what specifically is driving the cryovolcano activity at Enceladus, "one thing is clear: Enceladus cannot vent at this rate forever," Rymer told SPACE.com. "Scientists have been wondering whether the venting rate is variable, and these new data suggest that it is."

The scientists detailed their findings in the April 21 issue of the journal Nature.

Follow SPACE.com contributor Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Visit SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us