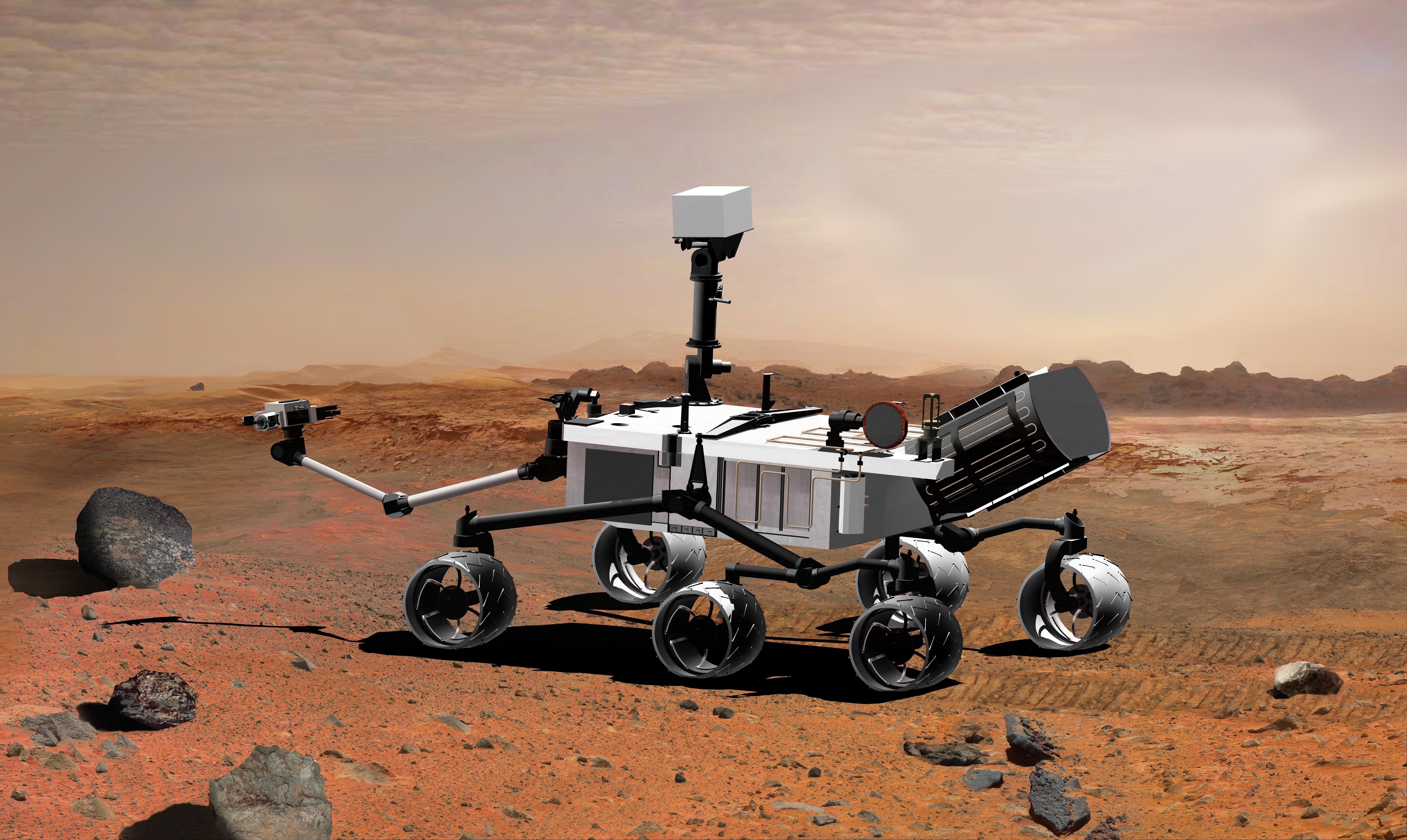

NASA's Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) mission will be humanity's most ambitious exploration yet of the surface of another planet.

MSL is due to launch from Florida around Nov. 25 of this year. In August 2012, the mission will drop a car-sized rover called Curiosity onto the Martian surface using a novel, high-precision landing system. The MSL spacecraft will slow its descent through the atmosphere with a parachute and retro-rockets, then lower Curiosity upright to the red dirt on a tether.

The main goal of the $2.5 billion MSL mission is to assess whether Mars has ever had an environment capable of supporting microbial life. To accomplish this goal, Curiosity will use 10 different science instruments — twice as many as were aboard NASA's Mars Exploration Rovers (MER) Spirit and Opportunity, which landed on the Red Planet in 2004 to hunt for signs of water.

NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., heads up the MER project, and it's leading MSL as well. On a recent tour of JPL, SPACE.com caught up with MSL project manager Pete Theisinger. While technicians worked on an upside-down Curiosity in a clean room below, Theisinger discussed the goals, progress and challenges of the MSL mission.

SPACE.com: So what are you guys doing with the rover right now?

Pete Theisinger: We have basically taken some equipment out of the rover that requires re-work. So that's what you see. The rover is upside down, because we get at it through the bottom, and mobility's off — you see the wheels are off. The turret is off because the drill is being re-worked as well. [Video: Building Curiosity: NASA's Next Mars Rover]

Right now we're doing re-work on the avionics and some cabling. We'll be done in about two more weeks. We'll put the rover back together, we'll do a surface test and then we'll have the pre-ship review. And the rover is scheduled to ship to Florida in [late] June.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The cruise stage and the back shell are ready to go to Florida, and they're due to ship sometime in the next week or so. These are both being flown on military transport, and we will stop in Denver to pick up the heat shield [which was built by aerospace firm Lockheed Martin].

SPACE.com: What are you most excited about with this mission?

Theisinger: This thing is just so much larger and more complex and more capable than MER was. And [it has] many more science instruments — 10 versus 5 — and a new entry, descent and landing [EDL] system. All that's really exciting from an engineering standpoint. [Infographic: Mars rover Curiosity]

But the real guts of the mission is the fact that we're going to be taking samples for the first time, actually ingesting samples into the SAM — Sample Analysis at Mars — and the CheMin instrument.

The payoff for this is going to be huge. The science has the potential to be really a major new chapter forward in Mars science. The new entry, descent and landing system has the capability to put much more capable payloads on Mars.

SPACE.com: Curiosity will investigate whether Mars is, or ever was, capable of supporting microbial life. How will it advance the science beyond what Spirit and Opportunity have been doing?

Theisinger: Spirit and Opportunity were geology missions. They were looking for signs of water, and they found it. This is taking the next step forward: to look at more detailed chemistry and mineralogy, and to see if there were true habitability possibilities, and to search for organics as well.

The TLS [tunable laser spectrometer] inside of SAM is capable of looking for methane, as well as other trace gases in the atmosphere. And there's a lot of additional capability in terms of the geochemistry and geology in the rocks.

SPACE.com: Are there any aspects of this mission that you're particularly nervous about? Obviously, it's a whole new EDL system, which looks like science fiction when you see the animations of it. [Video: Curiosity to Make Unusual Landing on Mars]

Theisinger: I know, I know [laughs]. Well, there's always a first time. We've done everything we know how to do in terms of the verification/validation program and the design analysis.

Just this last week, in the last system test, we ran a full-up EDL simulation, all the way from approach through the landing. It's as close to a real descent profile as we can possibly do on Earth, and that simulation ran very well.

And so to the extent we can test it on the ground, it worked really well for us, and we didn't really have any hiccups. So that gives us confidence.

Will the equipment work the way you want it to work? I think the answer's yes. We've got tremendous landing site photography with HiRise [a camera aboard NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter spacecraft], and so we really understand the terrain hazards in the landing sites.

And we understand the atmosphere, to the extent you can understand the atmosphere of Mars, having flown through it five or six times. But of course, it is the first time we're doing this [type of landing], and Mars is a dangerous place.

We're pretty confident that this will work. We've done everything that we know how to do. [Best (and Worst) Mars Landings of All Time]

SPACE.com: Landing a robot on the surface of another planet is a difficult thing to do. So you can never guarantee success; you can just take all the possible steps to give yourself the best chance.

Theisinger: Exactly correct. We were confident in MER, and we had four issues during the early part of the mission — three during the cruise, and the Sol 18 [Martian day 18] anomaly when we landed.

So, are there things buried in this design that could cause us operational issues? We don’t think so. We'd certainly fix them if we found them. But it's a complex beast, and you never know. That's what makes you nervous. It's the fact that you never know.

SPACE.com: MSL's mission is set for one Mars year, which is nearly two Earth years. Spirit and Opportunity landed with three-month missions, and Opportunity's still going strong more than seven Earth years later. Do you feel the MER rovers have raised expectations too high? Will people expect Curiosity to still be chugging along 10 years later?

Theisinger: I hope not. I hope their expectations aren't unrealistic. Clearly, from a design-analysis standpoint and from a testing standpoint, we have done what we normally do, which is test it for three times its design life.

So based on that, would we be surprised if it went six years? I don't think so. But the mission planning and everything is being promised on two, and that's what Level 1 [mission] requirements are, and so that's what we're signed up for.

SPACE.com: But there's a lot of work that this thing can get done in two years. It will be able to cover a lot of ground in that time.

Theisinger: Yes, and in fact it'll be able to get outside the landing ellipse. Both the roving capability as well as the duration of the mission will enable us to do that.

And the EDL system — we're flying a guided entry now. So rather than having this long, narrow landing ellipse, we have a 20- by 25-kilometer landing ellipse, and that gives us a lot of places to go to.

SPACE.com: You haven't chosen yet where the rover will land. There are still four candidates.

Theisinger: That's right. We're entering a set of landing-site reviews and workshops in the middle of May, and then we'll have a certification review in June. Then we'll go the administrator in late June or early July with a recommendation for which one of these four he should take.

SPACE.com: All four sites have a flat spot where it's safe to land, but they're all close to interesting topography that Curiosity can get to, correct?

Theisinger: That's right. That's true in Holden [crater] and Eberswalde [crater] and Gale [crater]. In Mawrth [Vallis], you actually do land on interesting stuff. And recent traverse studies have found that there are pockets of interesting stuff in Eberswalde as well.

SPACE.com: MSL was originally supposed to launch in 2009; it's had a two-year delay, as well as some cost overruns. What have some of the biggest challenges been in putting this mission together?

Theisinger: It always ends up, by the time you're done, being the schedule. You start out, and there are delays due to unforeseen circumstances. The technology that you were counting on isn't quite as mature as you thought it would be. The vendor has some kind of difficulties.

There are all kinds of things like that. And we've got to be able to get the integration and test program done to our satisfaction by the time we get to the launchpad. That's been the biggest challenge. And we have found some late issues, which has caused us to do some re-work.

Every time we do that, we take the vehicle down for a couple of weeks. This is the third time we've opened the vehicle to do some re-work. So that's been a challenge — to maintain the test program at the level we want, and at the same time as we're inserting these kind of surprises.

From a technical standpoint, it's been a challenge to get the drill and the sample processing done. It's been a challenge to get the radar done. It's been a challenge to get the avionics done.

But in the end, I don't think there are any technical compromises we made in any of those areas. It's cost us time, and it's cost our sponsor [NASA] and ourselves some money, but in the end I think we've gotten the vehicle we want to get. I'm very pleased with the technical capability of the vehicle, and I'm very pleased with the way the test program has gone.

SPACE.com: It's important to get everything right, even if it causes some delays or costs a little more. Because you can't really fix anything after launch.

Theisinger: That's right. And we certainly have that viewpoint. We're not going to launch this baby before it's time. But we feel confident that where we are, with the integration program and with test time that we still have to go, that we'll be fine.

SPACE.com: If this rover finds organics on Mars, what's the next step in Mars exploration? Is it a sample-return?

Theisinger: I think that's a question you ought to really direct to the program office. We've got the 2013 missions on the books; we're working to 2016 and 2018 developments with the European partners. The Decadal Commision put the sample-return mission as a very high priority. So those are kind of the facts on the ground.

In the world in which we live, and the budgets in which we live and those sorts of things, there's still a lot of heavy lifting to do.

SPACE.com: So what's the feeling going to be like in August 2012, when Curiosity lands and you see this rover cruising around on the surface of Mars? Will you guys pop a bottle of champagne?

Theisinger: Well, it depends on who you are. I think we're all going to feel great when it lands and we've got a rover operating on the surface of Mars. I remember when Spirit and Opportunity landed, they became absolutely priceless assets, because you've retired so much risk to get them to this place, and they can finally do their job.

But I pointed out to the guys when Spirit and Opportunity landed that we'd only satisfied one of the Level 1 requirements, which was to launch and land on Mars. We had this long list of other Level 1 requirements to go.

And it's going to be the same thing with this. The people who worked on EDL, they're going to be proud. They're going to be unbelievably happy with this, and their job will be a job well done. But for the scientists, at that point it's just come out of the garage.

So it'll depend on where you sit on the project. We'll all be tremendously pleased and happy, but for some people, it's the end of the story for them personally, and for some it's just the beginning.

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.