How to Clean Up Space Junk: DARPA's Orbital Catcher's Mitt

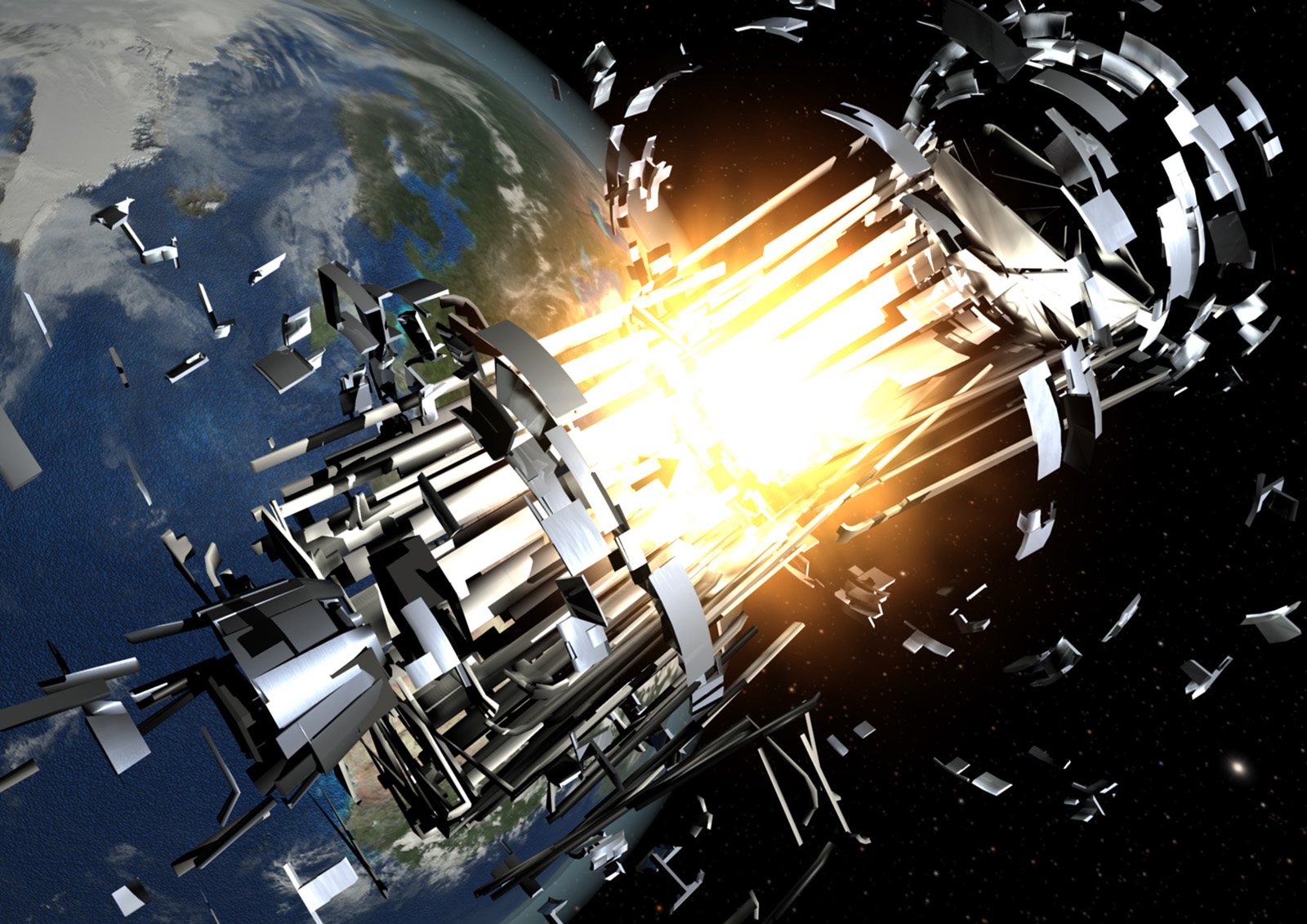

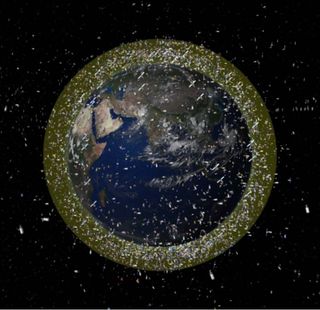

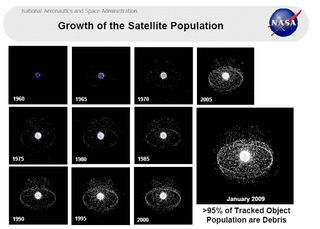

The Earth is surrounded by human-made orbital debris in all shapes and sizes that includes everything from abandoned satellites and leftover rocket stages to the tiniest paint chips and droplets from spacecraft coolant systems.

The hazard is very much real. Given the ultra-fast speeds of objects in space (satellites in low-Earth orbit fly at 17,400 mph), even the most minuscule bit of rubbish could create havoc if it crashed into a functioning spacecraft.

The question of how best to de-clutter outer space has produced a wealth of proposals: some whacky, whimsical or wanting of a sanity check. Many space junk clean-up ideas have already been proposed, including: catch-all space sweepers, fishing nets and harpoons, tethers, laser blasts, big and small space tugs.

One of the latest looks at the orbital debris quandary was completed by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA).

Released with little fanfare a few months ago, it was dubbed "The Catcher’s Mitt Study" – to assess the debris problem and its future growth, determine where the greatest problem will be for U.S. assets and then, if appropriate, explore technically and economically feasible solutions for debris removal. [Worst Space Debris Events of All Time]

Operation: Catcher’s Mitt

The report explains that active debris removal was found to be required at some point to maintain an "acceptable level" of operational risk.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Although projections show that it may take decades for the risk to become unbearable," there are several reasons to begin development of a solution today, the Catcher's Mitt study states.

A central finding of the study is that the development of debris removal solutions should concentrate on pre-emptive removal of large debris in both low-Earth orbit (LEO) a few hundred miles above the planet, as well as geosynchronous Earth orbit (GEO), the realm of communications satellites and other key spacecraft about 22,400 miles (36,000 kilometers) up.

More a warning than background to the vexing dilemma of orbital debris, the Catcher's Mitt study explains that "failure to address this problem has significant implications for the success of future space missions due to the potential increased number of on-orbit collisions with non-trackable, yet lethal, debris fragments."

Significant, but manageable

Although space debris is a growing concern and will have to be addressed at some point in the future, even in the most congested low-Earth orbit altitude regimes, the current risk from orbital debris is significant … but manageable, said Wade Pulliam, manager of Advanced Concepts of Logos Technologies in Arlington, Va., and the former program manager of DARPA’s Catcher's Mitt report.

"By significant I mean that it can be one of the top single contributors to the lifecycle risk of a satellite, but manageable in that the risk is still sufficiently low that it doesn't require a change in operations," Pulliam told SPACE.com.

Pulliam noted that a recent study by The Aerospace Corporation projected the effects of the future debris environment over the next 30 years. It showed that for typical low-Earth orbit satellite constellations, the risk of space debris will add only 4 to 15 percent to the cost of the constellation, depending on the type of constellation.

"Of course, debris risk is statistical, so there may not be any problem at all or a collision will take out a satellite requiring a spare to be built and launched," Pulliam said. Still, a new significant debris event could statistically happen tomorrow which would greatly accelerate the growing risk and require a more immediate response, he cautioned.

Tragedy of the commons

In the big picture, Pulliam said that he considers orbital debris a human-made environmental problem. [Video: Growing Threat of Space Junk]

"Although space is not an ecosystem per se, the problem is dependent on the cumulative effects of human activity over and above the ability of the nature system to balance like any other environmental challenge," Pulliam said.

Additionally, Pulliam advised that the constraints on finding an agreeable, cost-effective solution are remarkably similar to other current environmental issues. Specifically, the orbital debris problem can be characterized as a "tragedy of the commons."

The problem can also be explained by what is called "common but differentiated responsibility," which is also seen in other worldwide environmental challenges such as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and global warming, Pulliam pointed out.

"It is likely new space-faring nations will make a similar argument if current mitigations efforts prove to be insufficient to forestall the deterioration of the low-Earth orbit environment and an international agreement on debris removal is required," Pulliam advised.

There is a "therefore" to Pulliam's view: That is, if you are one that believes that debris has become a risk which will soon make operations difficult in low-Earth orbit, then a top-priority has to be in continued research into cost-effective methods to remove debris mass already in orbit. That's because this mass is what will cause the future growth in the debris population.

"There are many approaches that have been postulated for debris removal, but determining which are the most cost effective and demonstrating their utility is necessary to formulating a response to the overall problem with the lowest cost and risk," Pulliam said.

Up in the air

One lingering question that remains — putting think tank studies aside —is exactly who is in charge of orbital debris cleanup?

In the United States, the initial lead for Department of Defense (DoD) efforts regarding debris removal as called for in the new U.S. National Space Policy is reportedly the Office of the Secretary of Defense.

But still up for grabs (like space junk itself) is the delegation of the task to a particular organization within DoD. For example: the U.S. Air Force Research Laboratory; the Space and Missile Systems Center; or perhaps the Naval Research Laboratory.

"I think that the DARPA's Catcher's Mitt study clearly said that going after large, trackable, derelict debris is the most likely best recourse for debris cleanup," said Darren McKnight, technical director at Integrity Applications Incorporated in Chantilly, Va. "However, the best means to remove the large derelict objects is very much up in the air."

If history is any indication of the future, "the first large derelict debris removal action will most likely occur with a complicated, expensive rendezvous, grapple and move with a traditional propulsion system … though this approach will not scale well for the multiple objects that will likely have to be removed over the next few decades," McKnight told SPACE.com.

The price of delaying action

McKnight likens the orbital debris situation today to the observations of Nassim Taleb, author of "The Black Swan - The Impact of the Highly Improbable." The book describes the difficulty of dealing with highly improbable and highly unpredictable events that have severe repercussions.

Taleb accentuates the plight for those who try to prevent "Black Swans" because they are never appreciated if they are successful, since preventing something that was highly unlikely to begin with does not bring acclaim. Often, it is quite to the contrary; they actually get ridiculed for their attempts to prevent events that others have difficulty even imagining.

"I hope that we do not have such a situation with active debris removal actions. While the calculus of delaying action is much clearer, it will still require some vision from policymakers and technologists to act now to start real programs for active debris removal," McKnight said. "Nobody has won the Nobel Prize for preventing a disaster that never occurred."

Leonard David has been reporting on the space industry for more than five decades. He is a winner of this year's National Space Club Press Award and a past editor-in-chief of the National Space Society's Ad Astra and Space World magazines. He has written for SPACE.com since 1999.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years. Currently writing as Space.com's Space Insider Columnist among his other projects, Leonard has authored numerous books on space exploration, Mars missions and more, with his latest being "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published in 2019 by National Geographic. He also wrote "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet" released in 2016 by National Geographic. Leonard has served as a correspondent for SpaceNews, Scientific American and Aerospace America for the AIAA. He has received many awards, including the first Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History in 2015 at the AAS Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium. You can find out Leonard's latest project at his website and on Twitter.