Star That Changed the Universe Shines in Hubble Photo

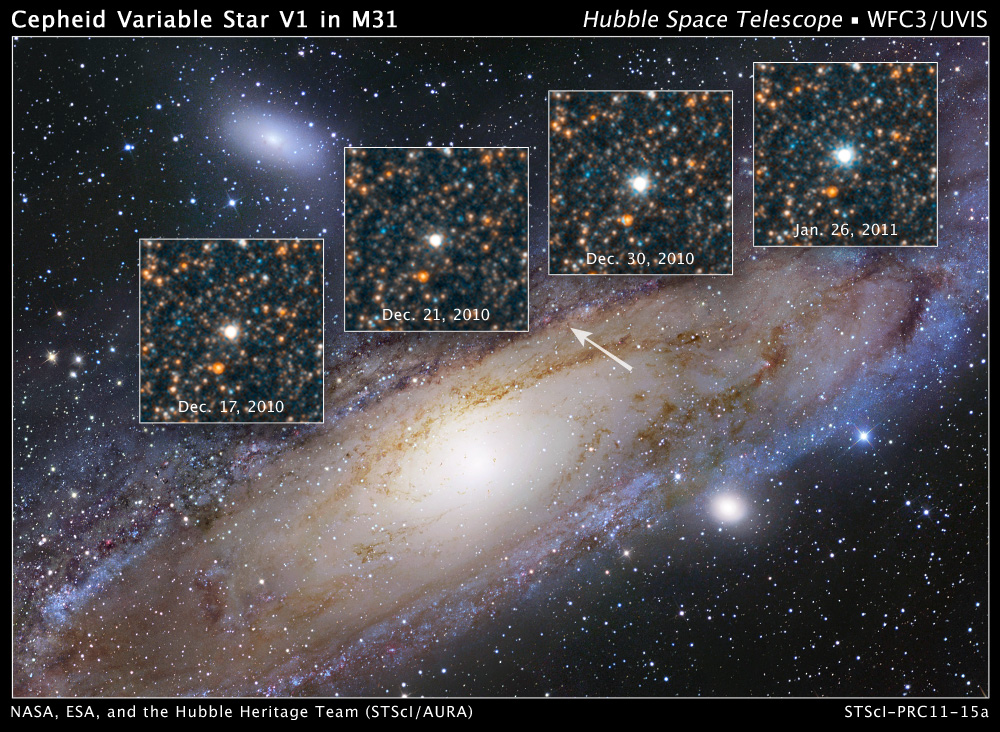

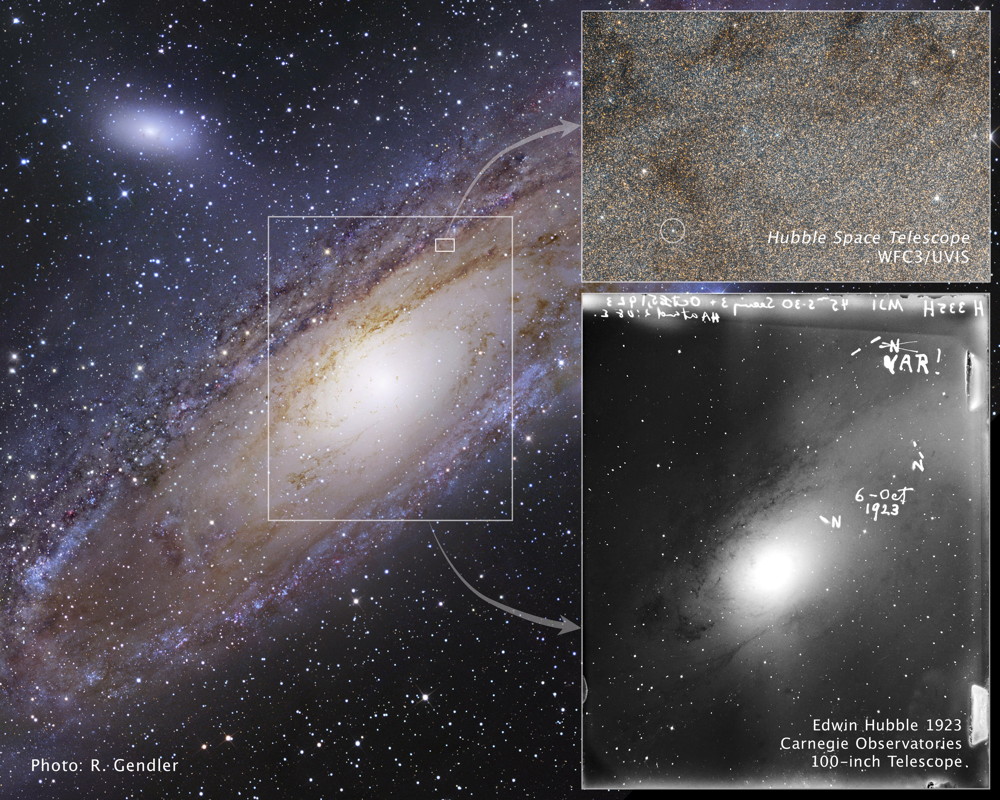

BOSTON — In homage to its namesake, the Hubble Space Telescope recently photographed a star that astronomer Edwin Hubble observed in 1923, changing the course of astronomy forever.

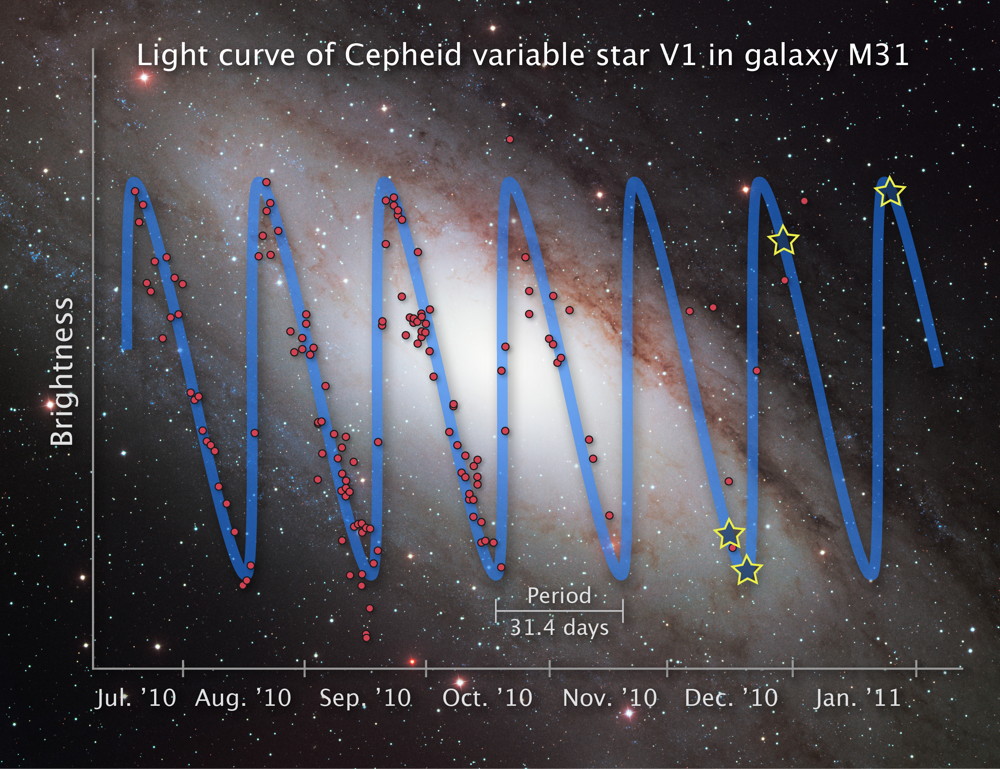

The star is a variable star that pulses brighter and dimmer in a regular pattern, which allowed scientists to determine its distance, suggesting for the first time that other galaxies exist beyond our own Milky Way.

"I would argue this is the single most important object in the history of cosmology," said astronomer David Soderblom of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Md., who proposed pointing the Hubble Space Telescope at the star. [See the Hubble photo of variable star V1]

The new Hubble telescope observations were revealed May 23 at the meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Boston.

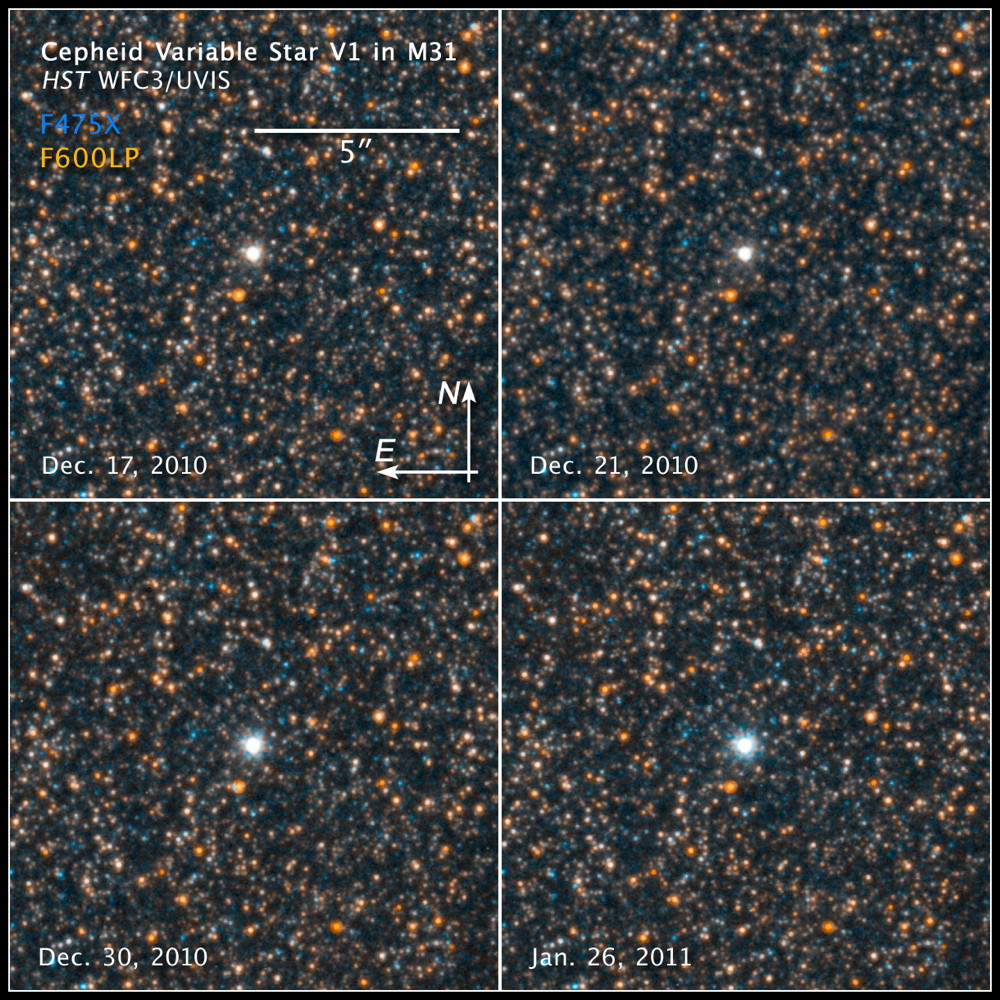

The star, called Hubble variable number one, or V1, is what's known as a Cepheid variable. The brightness of these stars varies as helium gas inside them heats and expands and then cools and contracts in a feedback loop. The period of this pulsation is closely linked with the intrinsic brightness, or luminosity, of the star. [Spectacular Hubble Telescope Photos]

By calculating a Cepheid variable's intrinsic brightness, and comparing it with the star's apparent brightness (which will get dimmer the farther away it is), astronomers can calculate the object's distance.

Before Edwin Hubble's discovery, many astronomers believed that the universe contained only one galaxy, the Milky Way. Some researchers argued that fuzzy objects called spiral nebulae, including a bright one called the Andromeda nebula, were actually galaxies in their own right.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

It was the observation of V1, which could be definitively established to lie farther than the bounds of the Milky Way, that proved other galaxies exist.

After reading a letter from Edwin Hubble describing the measurement, famed astronomer Harlow Shapley, famous for espousing the idea that the Milky Way was the only galaxy in existence, reportedly told a colleague, "Here is the letter that destroyed my universe."

The Hubble Space Telescope was named after Edwin Hubble. In fact, when the observatory was launched on space shuttle Discovery in 1990, the mission also carried copies of the photograph Edwin Hubble made of V1 in 1923.

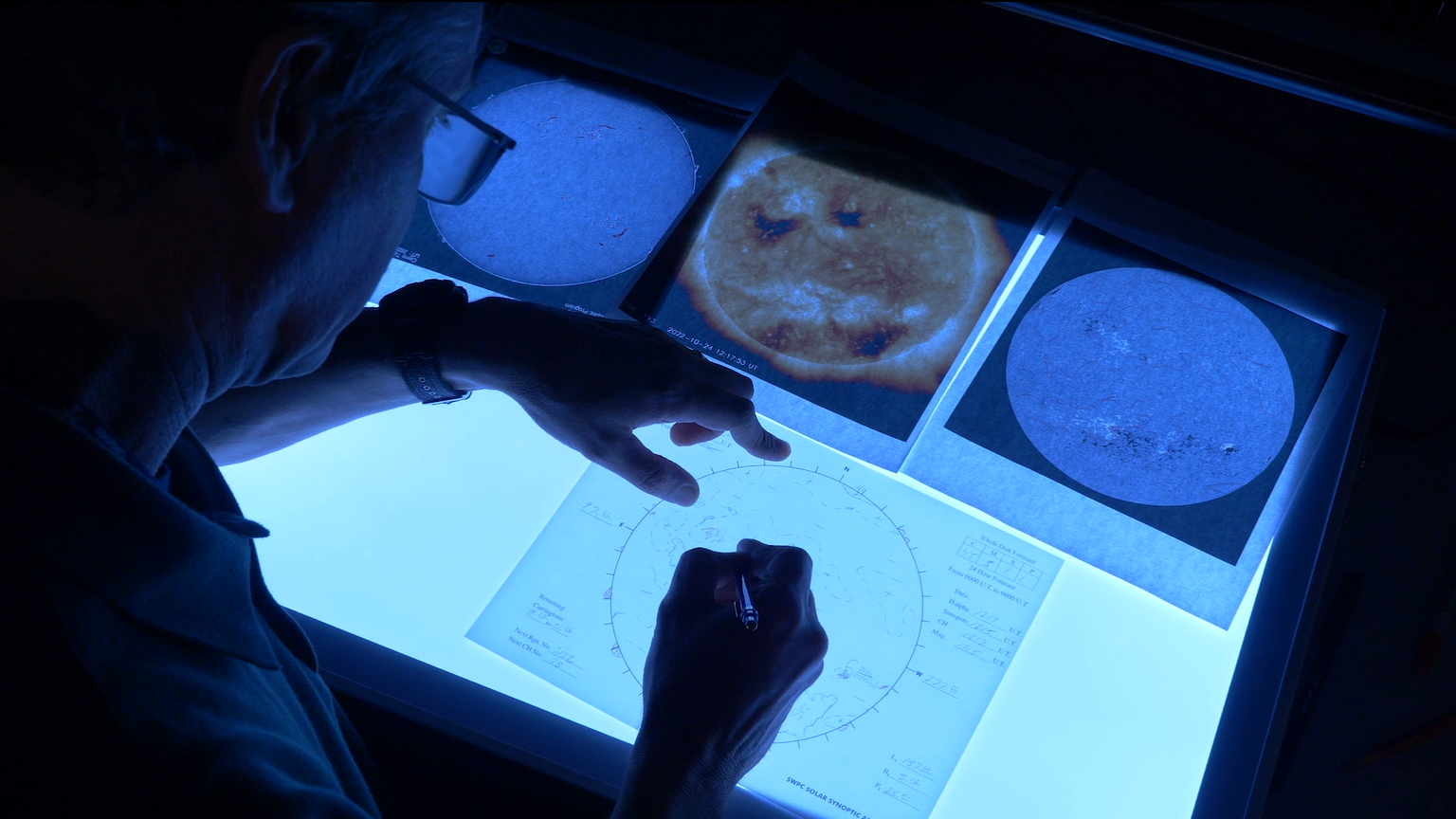

And in honor of this game-changing discovery, the Hubble Space Telescope pointed its lenses at V1 for the first time in December 2010 and January 2011. Hubble scientists partnered with amateur astronomers working with the American Association of Variable Star Observers, who took their own observations of the variable star to establish the best times at which to view V1.

Though the observations aren't breaking much new ground, science-wise, they're valuable as a way to tie present astronomy to its roots, said Lisa Frattare of the Hubble Heritage Project at the Space Telescope Science Institute.

"A scientist would not be able to take these observations," Frattare said, explaining that the science benefits of the observations would not be valuable enough to beat the competition for valuable Hubble observing time. "This is more of a public relations observation. It's a worthy thing that we went back and observed it. It was worth the orbits that we used."

Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.