Wednesday brings a partial solar eclipse to parts of Asia and North America, but it comes with an odd twist: At one point, the eclipse will be occurring at "midnight" between the two days this week.

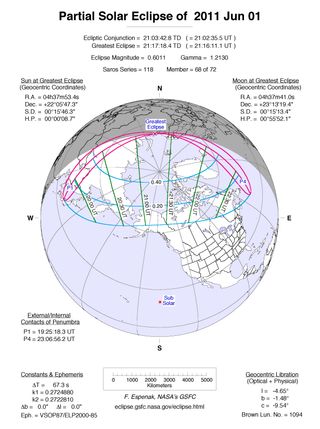

During the eclipse, the outer shadow of the moon (called the penumbra) will first fall on northeast Asia as the eclipse begins, and then work its way east across the International Date Line. Because of that timing, this eclipse will have the quirky circumstance of beginning on the morning of Thursday (June 2) and ending on the evening of Wednesday (June 1).

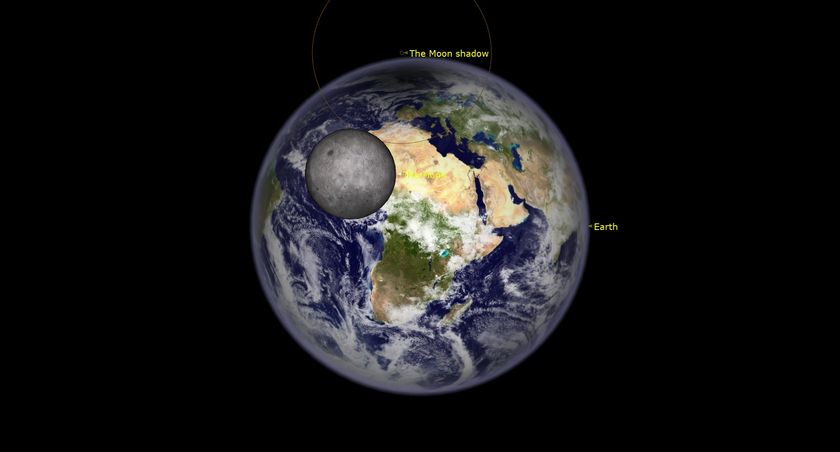

For this partial solar eclipse, the axis of the moon's shadow, the dark cone we call the umbra, actually never hits the Earth’s surface, passing about 843 miles (1,358 kilometers) above Cheshskaya Bay and the Bolshezemelskaya Tundra of far northwestern Russia. There, the sun will be seen to dip right to the northern horizon — at the "midnight" point of its 24-hour Arctic day — before climbing again.

During the few minutes in which the eclipse will reach its peak, with the top three-fifths of the sun bitten away by the moon, the sun will take on the appearance of a huge boat sailing out over the icy Barents Sea.

Greenland and Iceland are also within the eclipse zone, the latter getting a view just before the sun begins to set in their late evening.

Solar eclipses occur when the moon passes in front of the sun as seen from the Earth's surface. Total solar eclipses occur when the moon appears to completely block the sun, but occasionally the moon's only in front of a portion of the sun. These events can create partial and so-called annular eclipses. [Photos: The First Solar Eclipse of 2011]

While total solar eclipses, which can be viewed only from the narrow path of the moon's shadow on the Earth, partial solar eclipses can be seen across much wider geographical areas.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

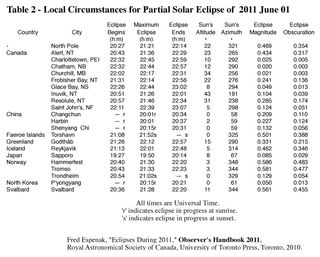

A NASA skywatching table available here details the local eclipse viewing times for different locations around the world. WARNING: NEVER stare directly at the sun with your naked eye or through binoculars or a telescope without proper light filters. Serious eye damage can result.

Alaska and Canada get eclipse views

For the North Americans, we might call this the "Alcan Eclipse" since it will be visible primarily from Alaska and northern Canada.

Indeed, the eclipse will be available to the northern two-thirds of Alaska (an early afternoon event), as well as northern and eastern portions of Canada, who will see the eclipse during the course of the afternoon, as the sun slowly descends toward the west-northwest horizon. The penumbral shadow finally passes over the Earth’s surface and cross over the open waters of the Atlantic to the east of Newfoundland, as the sun is passing out of sight. [Solar Eclipse Photos: The View From Space]

Skywatchers in Alaska who will see a very small, but noticeable, scallop taken out of the upper limb of the sun around 1 p.m. Alaska Daylight Time include those in Fairbanks, Nome and Barrow.

In Canada, careful viewers in the Maritime Provinces might be able to detect a tiny "dent" in the sun’s upper right rim. Charlottetown, P.E.I., Moncton, New Brunswick, Glace Bay, Nova Scotia and St. John’s, Newfoundland, are all just within the visibility zone of this upcoming eclipse.

One might wonder if any part of the contiguous (48) states will be able to see this eclipse and the answer is "yes," but just barely.

In Madawaska, located at the very top of the state of Maine, the dark moon will encroach upon the sun's upper limb at 6:39 p.m. EDT and move off of it just 10 minutes later. At maximum, the moon will obscure only 0.003 percent of the sun. [Eclipse-Chasing Retro Video]

To call this an "eclipse" for Maine skywatchers is being charitable, to say the least!

Be very careful!

Once again it needs repeating: looking at the sun without proper eye protection is dangerous. Looking at the sun is harmful to your eyes at anytime, partial eclipse or no.

Many people are under the mistaken impression that when a solar eclipse is in progress there is something especially insidious about the sun's light. But the true danger that an eclipse poses is simply that it may induce people to stare at the sun, something they wouldn't normally do.

The result can be "eclipse blindness," a serious eye injury that has been recognized at least since the early 1900s. About half of the reported victims of eclipse blindness recover their precious quality of eyesight after a few days or weeks. The other half carries a permanent blurry or blind spot at the center of their vision for the rest of their lives.

By far, the safest way to view a solar eclipse is to construct a pinhole camera.

A pinhole or small opening is used to form an image of the sun on a screen placed about three feet behind the opening. Binoculars or a small telescope mounted on a tripod can also be used to project a magnified image of the sun onto a white card. Just be sure not to look through the binoculars or telescope when they are pointed toward the sun!

A variation on the pinhole theme is the pinhole mirror.

Cover a pocket-mirror with a piece of paper that has a one-quarter-inch hole punched in it. Open a sun-facing window and place the covered mirror on the sunlit sill so it reflects a disk of light onto the far wall inside. The disk of light is an image of the sun's face.

The farther away from the wall the better; the image will be only one inch across for every 9 feet from the mirror. Modeling clay works well to hold the mirror in place. Experiment with different-size holes in the paper. Again, a large hole makes the image bright, but fuzzy, and a small one makes it dim but sharp.

Darken the room as much as possible. Be sure to try this out beforehand to make sure the mirror's optical quality is good enough to project a clean, round image. Of course, don’t let anyone look at the sun in the mirror.

Unacceptable filters include sunglasses, color film negatives, black-and-white film that contains no silver, photographic neutral-density filters and polarizing filters. Although these materials have very low visible-light transmittance levels, they transmit an unacceptably high level of near-infrared radiation that can cause a thermal retinal burn.

The fact that the sun appears dim, or that you feel no discomfort when looking at the sun through the filter, is no guarantee that your eyes are safe.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for The New York Times and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, N.Y.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.