Huge Heat Shield Has Huge Task: Protecting NASA's Next Mars Rover

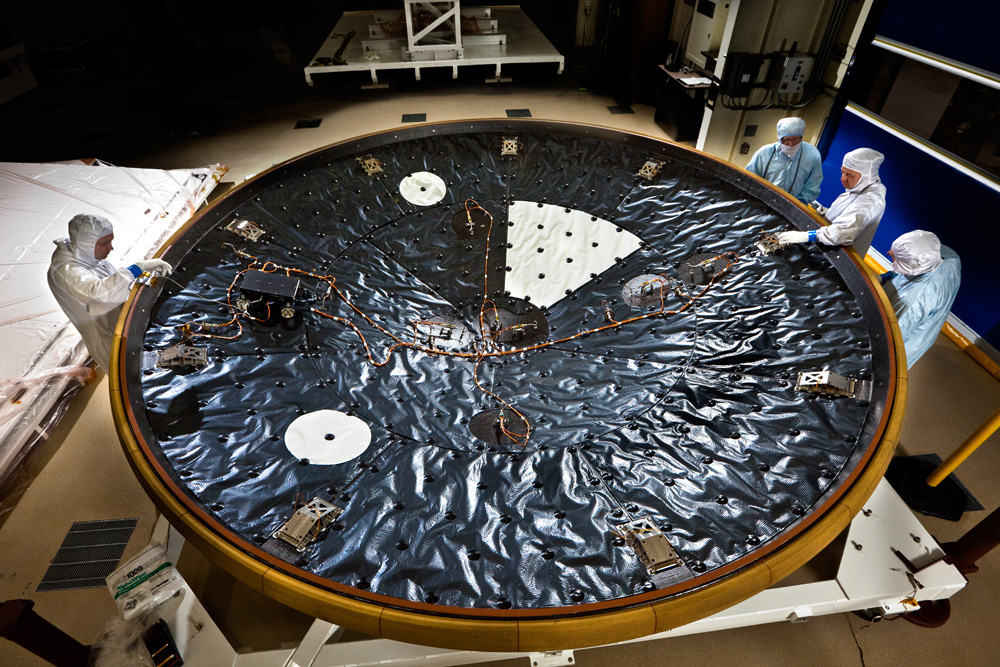

When NASA's newest Mars rover dives into the Martian atmosphere next year, it will be cocooned in the largest "beat the heat" system ever sent to the Red Planet.

To ensure that the nuclear-powered rover — called the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL), or "Curiosity" for short — survives its fiery entry and reaches a pinpointed landing spot, it will have a huge heat shield and back shell that together form a protective aeroshell.

The heat shield is outfitted with something called the Mars Science Laboratory Entry, Descent and Landing Instrument (MEDLI) — a set of sensors that will record atmospheric conditions and gauge how well the heat shield thwarts the brutal welcoming that Curiosity will receive high above the red Martian dirt.

The Curiosity rover’s mission to Mars will make a guided entry, one that is controlled by small rockets during its blazing fall through the Martian atmosphere.

Screaming toward Mars, Curiosity’s angle of attack will employ a lift-to-drag ratio in excess of that ever flown at Mars. The flow around the MSL spacecraft is expected to become turbulent early in the entry. The resulting heat flux and shear stress on the heat shield will be the highest ever encountered at the planet, researchers say.

Before atmospheric entry, tungsten ballast will be tossed off the spinning spacecraft, changing its center of gravity. More blocks of ballast will be ejected to give the spacecraft its desired angle of attack. Once the vehicle is through the majority of the hot entry, added ballast will be tossed off to realign the vehicle for parachute deployment. [Vote Now: Where Should the Next Mars Rover Land?]

All in all, the convergence of so many firsts for MSL’s blistering entry is sure to add up to a heart-stopping, nail-biting encounter of the planetary kind.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Uncertainty factor

MSL’s aeroshell/heat shield, designed by the aerospace firm Lockheed Martin, is the largest ever built for a planetary mission, nearly 15 feet (4.5 meters) in diameter. By contrast, the heat shield on NASA's Apollo capsules for return to Earth measured just less than 13 feet (4 m). [Video: Curiosity Rover’s Unusual Mars Landing]

Space engineers like to build in generous helpings of margin. In today’s aerospace world, extensive use of computational fluid dynamics — computer runs that can simulate high-velocity airflow — help them calculate this margin.

"But you always have to throw an uncertainty factor on that because you’re not completely sure," said Bill Willcockson, a senior staff member and heat shield expert at Lockheed Martin Space Systems, near Denver.

Willcockson said Curiosity’s entry system will yield better insight into the heating environment experienced by the spacecraft.

"This is real data for the real Mars atmosphere," Willcockson told SPACE.com. "Getting this information back from MEDLI is going to very important … to help future missions and to have more confidence that predictions are in the ballpark."

Demonstrating guided entry into Mars is a key to future Mars missions, Willcockson added. "Trying to get precision landings is important so that you can go toward smaller areas that are scientifically interesting targets." [Best (and Worst) Mars Landings of All Time]

MSL's entry, descent and landing system aims at touching down within a 12.4-mile (20 kilometers) landing circle, mission scientists have said.

Heart of the fire

MEDLI was developed by NASA's Langley and Ames research centers. As its name hints, the gear is meant to produce a medley of engineering information from various sensors.

The MEDLI suite consists of seven integrated sensor plugs and seven Mars Entry Atmospheric Data System pressure sensors. They are located on the heat shield's exterior; mounted inside it is a Sensor Support Electronics box that provides power, signal conditioning and analog-to-digital conversion.

Under consideration is real-time relay of information from select MEDLI sensors during entry. However, the full dataset collected by MEDLI will be transmitted back to Earth a month after Curiosity’s landfall.

As for the placement of the sensors on the heat shield, "they are right in the heart of the fire," said Rich Hund, MSL program manager at Lockheed Martin Space Systems Co.

Hund said Lockheed Martin integrated MEDLI onto the back of the heat shield. Then that major piece of aeroshell hardware was airlifted to NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on May 12.

Late last month, there was an incident at KSC involving the MSL's back shell: a crane operator mishandled the hardware. It was later deemed not to be an issue, and the component has been given a thumbs-up for flight.

Curiosity's sojourn to Mars is expected to begin next week, with the rover's transfer from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., to central to Florida for encapsulation within the enormous aeroshell.

"Work on the Mars Science Laboratory is continuing on schedule for shipping Curiosity and the descent stage to Kennedy Space Center next week and for launching the spacecraft during the Nov. 25- to-Dec. 18 period this fall," JPL spokesman Guy Webster told SPACE.com.

Plummeting profile

After some six years of work on Curiosity’s heat shield, its builders are abuzz with anticipation.

"I’ve got a very big smile on my face," Hund told SPACE.com. "For a planetary mission, this was a bit more challenging because of the size. All the logistics, transportation, and tooling … it was definitely bigger than anything we’ve done before."

Concerning the heat shield, the toughest issue came late in the game, Hund said. That was the decision to use a Phenolic Impregnated Carbon Ablator (PICA) thermal protection system instead of the Mars heritage SLA-561V — the type of heat shield material that has flown on all of NASA's successful Mars entry missions.

Tests of the SLA-561V material under expected Mars atmospheric entry conditions for Curiosity revealed shortcomings that could not be fully explained.

Given the aeroshell’s size and mass, the environment MSL will face on its plummet toward the surface will be hotter and have shear forces greater than any previous Mars mission.

The PICA material was invented by Ames Research Center. This will be the first time it has flown on a Mars mission.

Proven by test

Embedding MEDLI sensors into the rover’s heat shield also caused initial heartburn.

Why drill holes into a perfectly good heat shield?

"That was one of the basic questions," Willcockson acknowledged. But NASA technicians carried out numerous high-energy arc jet tests to ensure MEDLI sensors wouldn’t compromise the integrity of the heat shield and create a "runaway condition," he said.

"The key was it was all proven by test," added Hund.

Willcockson fondly recalls up-close looks at the heat shield of the Mars rover Opportunity back in late 2004. "We were lucky in that the heat shield happened to land close enough, but also in a direction that the scientists wanted to go," he said.

It's too early to tell whether a similar opportunity to scrutinize Curiosity’s heat shield is in the cards.

Similarly, having NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) spacecraft snap an image of MSL headed toward a landing is at a wait-and-see discussion stage.

The sharpshooting MRO caught NASA’s Phoenix Mars Lander en route to its touchdown on May 25, 2008 — the first time that a spacecraft had caught on camera the final descent of another spacecraft onto a planetary body.

Countdown clock is clicking

Along with the heat shield now at the Kennedy Space Center are the back shell and cruise stage of MSL. The Curiosity rover and its descent stage will be shipped to Florida shortly. Putting all the pieces together for the MSL mission is yet to come.

In the interim, the countdown clock is clicking away as Earth and Mars swing into favorable position, with MSL’s liftoff atop an Atlas V 541 booster slated between Nov. 25 and Dec. 18, 2011.

Arrival and entry is expected in August 2012.

"The size of this … it’s huge. The weight, the ballistic number is double anything we’ve ever flown into Mars’ atmosphere. Then the rover… it’s a large payload … a Mini Cooper," Willcockson concluded. "That’s going to be quite an achievement using this system."

Leonard David has been reporting on the space industry for more than five decades. He is a winner of this year's National Space Club Press Award and a past editor-in-chief of the National Space Society's Ad Astra and Space World magazines. He has written for SPACE.com since 1999.

Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years. Currently writing as Space.com's Space Insider Columnist among his other projects, Leonard has authored numerous books on space exploration, Mars missions and more, with his latest being "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published in 2019 by National Geographic. He also wrote "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet" released in 2016 by National Geographic. Leonard has served as a correspondent for SpaceNews, Scientific American and Aerospace America for the AIAA. He has received many awards, including the first Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History in 2015 at the AAS Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium. You can find out Leonard's latest project at his website and on Twitter.