Spinning Robotic Landers Make Space Exploration a Hop and Skip

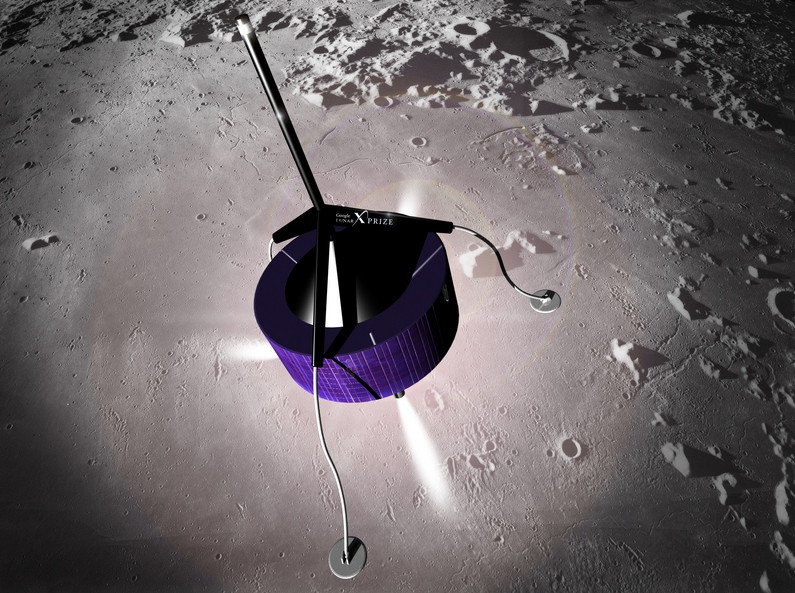

LAUREL, Md. — A former robot contender for the Google Lunar X Prize may find resurrection as a robotic lander for surface missions to planets and moons across the solar system. Its secret rests in a spinning midsection based on proven satellite technology that ensures almost unshakable stability.

The spinning lander could land and hop across alien surfaces on springy legs that have the flexibility "between a golf club shaft and a fishing pole," said Rex Ridenoure, president and CEO of Ecliptic Enterprises in Pasadena, Calif. His company holds pending patents on the space technology that originated with Harold Rosen, a satellite pioneer.

One version of the lander intended for an asteroid mission might have extra detachable harpoon legs to temporarily anchor itself to the rock, Ridenoure told a crowd of scientists and engineers at the 9th IAA Low-Cost Planetary Missions Conference here. Another version aimed at Europa might add a drill for tapping the Jupiter moon's icy secrets. [Best and Worst Mars Landings]

Whatever the destination, the spinning design ensures a relatively easy landing compared to most space missions.

"The neat thing is that the thing will not tip over," Ridenoure said. "The thing will just hop and bounce and skitter until it comes to a stop."

That vision began with Rosen, a former engineer for the Hughes Aircraft Company who first harnessed spinning back in 1965 as a way to stabilize satellites holding the same geostationary orbit above the Earth. His dual-spin design kept the main satellite body spinning while an instrument platform remained motionless.

Space explorers such as Galileo have also used the dual-spin concept. But even after Rosen retired from Hughes Space & Communications (now Boeing Satellite Systems), he harbored unfulfilled hopes of using spinning for stabilized robotic landings.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Rosen got his chance when the Google Lunar X Prize first debuted in 2007. The lunar landing competition offers a $20 million grand prize for landing a robot on a lunar surface, having it travel at least 1,650 feet (500 meters) and send data and images back to Earth.

The Southern California Selene Group formed by Rosen to compete in the Google Lunar X Prize included Ridenoure at Ecliptic Enterprises. The team designed a three-legged robotic contender, but eventually withdrew from the competition in 2008 after expressing philosophical differences with the X Prize Foundation's vision for commercializing space and human exploration.

But the spinning lander concept has not died.

Rosen handed off the technology to Ecliptic, and the company is now fielding queries from anyone interested in a possible low-cost lander mission. For comparison, the Southern California Selene Group had planned on a total mission cost of $20 million to $30 million while competing for the X Prize.

The spinning lander is small enough to reach many solar system targets by riding aboard a private Falcon 9 rocket developed by the commercial spaceflight firm SpaceX, Ridenoure said. And there is always the opportunity to pull up stakes and move if the original landing site doesn't work out.

"Once you get down on the surface, if you rotate the payload around and don't like the site, you can hop to another one," Ridenoure said.

You can follow InnovationNewsDailysenior writer Jeremy Hsu on Twitter @ScienceHsu. Follow InnovationNewsDaily on Twitter @News_Innovation, or on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Jeremy Hsu is science writer based in New York City whose work has appeared in Scientific American, Discovery Magazine, Backchannel, Wired.com and IEEE Spectrum, among others. He joined the Space.com and Live Science teams in 2010 as a Senior Writer and is currently the Editor-in-Chief of Indicate Media. Jeremy studied history and sociology of science at the University of Pennsylvania, and earned a master's degree in journalism from the NYU Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. You can find Jeremy's latest project on Twitter.