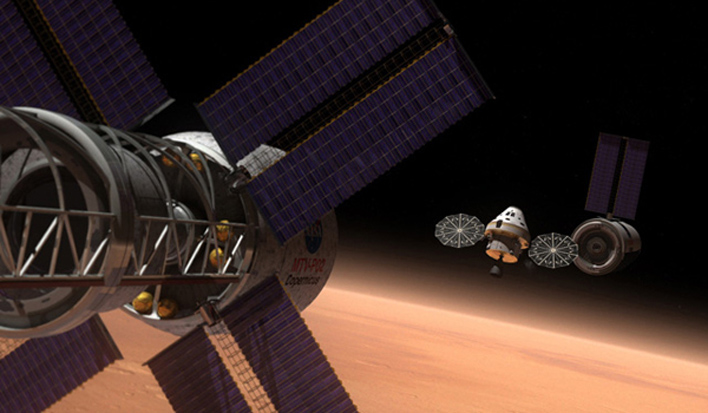

When the space shuttle Atlantis lands this month after its final STS-135 mission, NASA will enter a new era, one that focuses on getting humans to an asteroid by 2025 and Mars by the 2030s.

But the shuttle program's retirement affects more than just NASA. It will have far-reaching impacts across the entire aerospace industry, since many companies have helped develop and support the shuttle program since its inception in 1972.

One of the firms that is already feeling the impact is Pratt & Whitney Rocketdyne, the California-based outfit that builds the space shuttle main engine (SSME). SPACE.com caught up with Pratt & Whitney Rocketdyne president Jim Maser before Atlantis' July 8 launch to talk about the end of the shuttle era, the future of human spaceflight — and what comes next for the aerospace industry.

SPACE.com: What are your thoughts as the end of the shuttle era looms?

Jim Maser: First of all, it's just been a tremendous 30-plus years. For us, it's been an incredibly successful program.

When I first came in, I thought that it would be sort of an ancient system, kind of old and probably baselined and put into steady production for a long period of time, which is what we would have done in the commercial world. And I was pleased to learn that we have been continually investing and upgrading the space shuttle main engine — in cooperation with NASA, of course — and modernizing it as we go along.

It's unlike anything I've seen in the commercial world, in terms of the investment and core understanding that we have gained of this high-performance liquid hydrogen engine that I am 100 percent certain is unparalleled in the world.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

SPACE.com: What are you going to do with the space shuttle main engine now? Are there other applications, or will it just become a museum piece?

Maser: First of all, everything we've learned from it could apply to other hydrogen engines we're building. And we're currently in production on the RL-10, which is a hydrogen engine. The RS-68 is in production; both of those are used on the EELV [evolved expendable launch vehicle] side. And we're in development on the J-2X engine, the upper stage engine.

Second of all, as we understand it, it's still in the trade space for the Space Launch System beyond-Earth-orbit launch vehicle. So if NASA, in doing their system-level trades, decides that they think the SSME tends to fit in that trade space better, we have been working on a way to evolve it to a configuration that would be expendable and a lot more affordable to build.

So I think regardless of whether that configuration gets baselined or not, certainly we'll have a legacy of the knowledge from multi-decades of operation of that engine that we're working to include in all of our knowledge management standard work and education of our personnel going forward.

SPACE.com: Speaking of going forward: You're concerned that NASA's post-shuttle direction is too murky. You testified before Congress to this effect in March, saying that NASA needs to get a plan drawn out, or the aerospace industry is going to lose a lot of people and a lot of knowledge pretty soon.

Maser: That's exactly right. In my testimony, I said we compare it to when the Apollo program ended. The last moon landing was '72, but Apollo continued, with Skylab and Apollo-Soyuz, through '75. But the space shuttle had been baselined and turned on by President Nixon in early '72. [The Most Memorable Space Shuttle Missions]

So there was a clear overlap. People knew that there were going to be budget challenges, but everyone knew what we were going to work on. We could plan for it. And here we are, with the last shuttle launch on July 8, and we have no idea what we're doing next. I think that is a critical situation to be in.

We do understand that NASA is trying to move out very aggressively on being able to make the decisions they need to make and let everyone know where we're going next in terms of beyond-Earth orbit. It's part of a larger model.

What the model's about is saying, let's, as cost-effectively as possible, take cargo and crew to orbit. And part of that model is, we should be able to do that very cost-effectively procuring on a commercial basis, because we've spent 50 years maturing this technology. Going to low-Earth orbit is, aside from going suborbital, about as straightforward as things can get.

And so, the idea then is that, if you do this cost-effectively, you free up funding and your best and brightest to go do a big part of NASA's charter, and that is to explore.

This integrated model is critical to the health of our technical capability, critical to leadership in space and critical to ultimately attracting people to science, technology, engineering and math. Whether people go into space or not, it sparks their interest. And that interest in science, technology, engineering and math is what drives innovation, which ultimately keeps us competitive in the world marketplace.

SPACE.com: NASA has its plans; it wants to get humans to an asteroid by 2025, then to Mars by the mid-2030s. And it announced recently that its next-generation MPCV spaceship will be based primarily on the Orion capsule. Do you think NASA should do more, or should be more specific?

Maser: There are certainly other things they can do, and maybe a little bit earlier. You could go out and do a lunar orbit relatively quickly, to prove that we can do that sort of thing again. Or LaGrange points you could do relatively soon.

One of the things we're arguing for is, let's get started now, and we can build a vehicle that can go beyond Earth orbit relatively quickly. [Giant Leaps: Top Milestones of Human Spaceflight]

What you can do is start off with relatively simpler missions, and you could flex up your performance over time. You can go beyond Earth orbit with the very first vehicle you build and start flying. And none of that money's wasted, because that becomes the base of an architecture you can build upon for evolved higher performance or flexible performance.

SPACE.com: So the important thing is to have something in place, so people don't fade out of the workforce because they don't know if there are going to be jobs or opportunites going forward.

Maser: That's absolutely critical. We have to get started on something this summer. We have a lot of people working for us that wonder what the future holds for them. And it's very difficult as a leader of the organization to say, "I'm not sure."

If something isn't set forth in the next few months, I think the entire industry will have no choice but to continue reducing staff. And I think we'll start cutting into the bone at that point. I don't think this nation can afford that.

The key is getting into something we can get started on right now, will be able to have some launch capability in a decent timeframe and has the ability to evolve its performance to more complex missions over time.

SPACE.com: When you say NASA should lay something out this summer, do you mean just the basic architecture of the next-generation heavy-lift rocket, the Space Launch System? Or something else, too?

Maser: I think ideally they would identify what the Space Launch System architecture is, identify what it would be over time and identify what kind of objectives it would go after. You might start with some types of demonstration launches. And that would evolve into increasingly complex missions over time.

But you're not just working on something that does something in 2025. We believe there could be a lot of valuable exploration done leading up to something in 2025.

SPACE.com: The U.S. has been the world leader in space technology and space assets for a long time. Do you worry that, if we don't get in gear, we could cede that leadership to another nation?

Maser: I think it's a very real possibility. I think we're in a very fragile situation right now.

Countries like China, countries like India, and further behind you see South Korea — they're making big investments to be players. So if we want to have a say in what's going on, at the minimum, we have to show up. I think we are at a very critical time relative to that. I think a lot of people recognize that now, and there is a higher sense of urgency.

But I think we have to maintain the pressure, because this links very closely to national security, and security of information, and I think it's critically important to this nation. [Top 10 Space Weapons]

These skills are not easily built back up once they go away. It's a fairly specialized arena, and it requires a fair amount of experience, and our workforce isn't getting any younger. So we need to get the young folks in and show them that, if they work hard and work well and execute and also experiment and innovate, they can have a good career in this industry. And that's very questionable right now.

SPACE.com: You guys do a lot of rocket work, but you're also developing scramjet technology. Do you think scramjets will be operational in the next 20 years or so? What's the outlook?

Maser: We've had enough success with it that I view it as a major game-changer. In the short run, what we see it as is for one-way missile delivery systems for rapid global access over a long range. We think that the technology could mature enough to get into full engineering-manufacturing-development toward the second half of the decade and be an operable system by the end of the decade for that kind of scale.

And then from there you would go to other systems that could potentially do reconnaissance of some sort.

I would say overall, I'm very optimistic about this technology. This is something that could transform aerospace altogether, in my opinion. I view it as a long-term play. But I think what we've demonstrated is that the technology is getting mature enough that it could turn into something useful by the end of the decade.

SPACE.com: Are you optimistic about the future of human spaceflight, despite some of the issues we've talked about?

Maser: Yeah. In the short run, I would say I'm cautiously optimistic. The conversations I'm hearing going on about what we could potentially do about this, getting some traction on this model in both low-Earth orbit and beyond-Earth orbit — it really is kind of a flexible path of increasingly complex missions.

The key is that we come up with something that is robust enough to survive multiple administrations and multiple Congresses. I think if we can do that, and if we can show that we can give a good bang for the buck, and show a consistency to meet plans and budgets, that it can become enduring. So I am optimistic.

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.