Mystery From the Sun: Huge Solar Storm Still Puzzles 11 Years Later

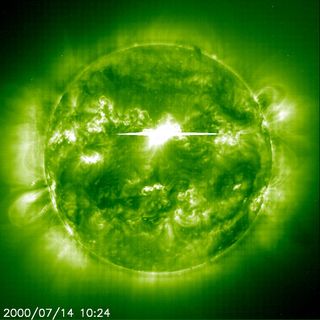

Eleven years ago this week, one of the worst storms on record raged on the sun, churning huge amounts of plasma around the solar surface and spewing massive loads of particles into space and toward Earth.

The July 14, 2000, event, called the Bastille Day Solar Storm, was a turning point for scientists' understanding of weather on the sun.

"It was one of the most highly observed events of that time," said Phil Chamberlin, a scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., who is a deputy project scientist for NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory, a sun-studying satellite that launched in February 2010. "It led to a lot of the requirements for the solar missions of today, like SDO."

X-Class

The Bastille Day storm was classified as an X5 eruption. X is the highest class of solar flare, though within that class, some events — such as an X17 storm that occurred in October 2003 — have been even stronger.

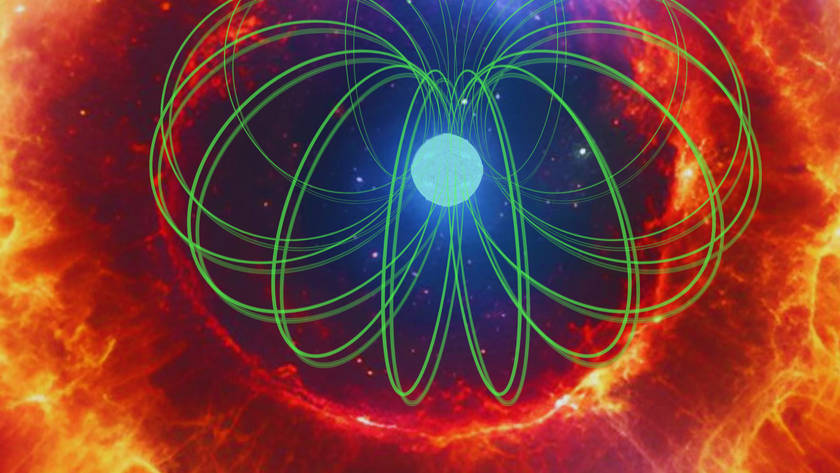

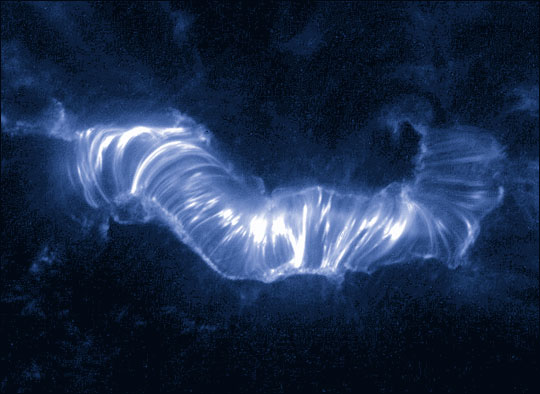

But back in 2000, on France's National Day, the flare that raged on the sun was the biggest since 1989. It occurred when magnetic field lines got tangled into a twisted sunspot. Eventually, pent-up energy was released and converted into heat and light. Particles on the sun sped along loops that traced magnetic field lines through layers of the solar atmosphere, and some were accelerated out toward Earth.

These particles bombarded our planet with a shower of protons that caused some satellites to short-circuit and led to some radio blackouts. [Big Blast on Sun Seen in 4-Scope View]

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Overwhelming the instruments

The storm provided useful fodder for researchers trying to piece together how solar flares occur on the sun and what sparks them.

"It was just a perfect example of a flare and how, in theory, flares work," Chamberlin told SPACE.com. "It fits a lot of the standard theories of how flares work. It was a really big event and it was right there in the center of the sun. We had some of the best instruments at the time looking at it."

However, some instruments in place to study the storm didn't prove up to the task. The Extreme ultraviolet Imaging Telescope (EIT) on NASA's SOHO satellite found itself so bombarded by high flux from the sun that it became saturated and couldn't record any useful readings, said Joe Gurman, a project scientist for the EIT instrument.

"It was exceptional, but it wasn't terribly useful because very soon after the beginning of the event, our image was blocked," Gurman said. "It's just like driving a car through the snow," he said, comparing the saturated instrument to a car's windshield that gets completely whited-out.

But the event did teach the researchers a lesson for the future.

"We learned more about how to operate our instruments during extreme solar activity," Gurman said. SOHO is still running strong.

Ramping up activity

Activity on the sun waxes and wanes on an 11-year cycle. The sun is now coming out of itsminimum period of activity, and moving toward a maximum that should occur around the end of 2013.

It's possible that we'll soon be in for another Bastille Day-class sun tantrum.

"The chances of seeing an X5 flare — I think they're pretty good coming up in the next few years, but who's to say?" Chamberlin said. "We definitely can't predict solar flares as much as we wish we could. That’s the point of all these missions. We're hoping scientists can collect enough data to predict these kinds of events."

You can follow SPACE.com Senior Writer Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.

Most Popular