How I Caught the Last Shuttle Out of Town: One Veteran Reporter's NASA Tale

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. — Watching the Atlantis orbiter rise into the sky, serving as the curtain call on NASA's space shuttle program, was a bittersweet and reflective moment for me. I had stood at exactly the same spot over 30 years ago to witness the maiden shuttle voyage of Columbia.

Now, not only did the nearby countdown clock show its age. I, too, had succumbed to the weathering of the intervening decades. Less hair, not as thin … still fully charged with a reserve of space spirit, but mixed with an overdose of adulthood cynicism.

Since that first shuttle liftoff in 1981, the space shuttle program has delivered soaring successes, albeit at great cost. That roster of achievement includes hurling more than 350 astronauts from 20 nations into space; fixing and upgrading the Hubble Space Telescope; dispatching satellites and interplanetary spacecraft; linking up with the then-Soviet Union's Mir space station; and, in Tinker Toy fashion, piecing together the massive International Space Station.

I've been fortunate to see the entire fleet of orbiters take to the air: Columbia, Challenger, Discovery, Endeavour and Atlantis.

But still fresh in my mind is that kick-start mission of the shuttle era — the STS-1 flight of Columbia on April 12, 1981. [Photos: NASA's First Space Shuttle Flight: STS-1]

Beyond cramped capsules

I had been writing for years about the building of Columbia and the first orbital flight test. The scope of what the shuttle was supposedly capable of delivering seemed a risky, bold gamble.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Whatever it was, we had clearly moved beyond cramped capsules as a form of space transportation. This baby had wings!

Still, getting Columbia flight-ready was fraught with growing pains. Reusable main engines, giant recoverable solid rocket motors, a mammoth external fuel tank — each component was a techno-troublemaker. Getting them to all fly in formation seemed unattainable.

Then there were those tiles. Applied in seemingly crazy-quilt fashion, the orbiter's heat-thwarting thermal protection system would give any outsider pause. It smelled of a jerry-rigged, Rube Goldberg "beat the heat" idea.

Flinging of flesh

Standing there that Sunday, April 12 — after a two-day delay due to a computer glitch — the Columbia space shuttle stood ready for blastoff. As a piloted-space-vehicle virgin, I had never seen the flinging of flesh real-time. Up to then, I had been glued via television to all those Mercury, Gemini, Apollo, Skylab, and Apollo-Soyuz space shots.

Thanks to prior Enterprise glide tests carried out by NASA's Dryden Flight Research Center at Edwards Air Force Base in Southern California, everyone knew the winged vehicle could at least glide.

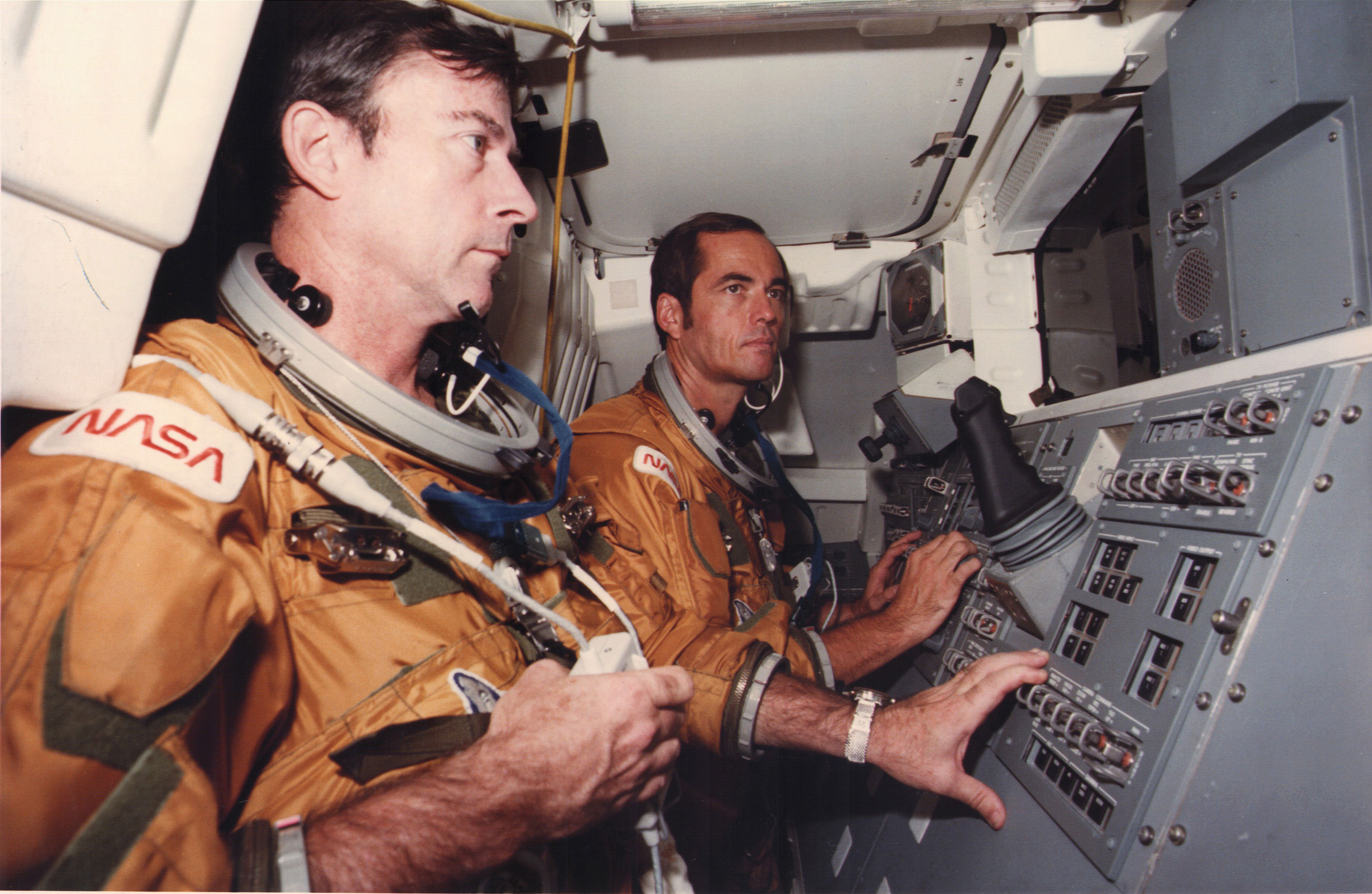

However, what Columbia had to go through first time out of the launch gate would be far more perilous. Strapped in tight and tucked into ejection seats were Columbia's gutsy twosome, commander John Young and pilot Robert Crippen. [Q&A With Bob Crippen, First Space Shuttle Pilot]

Quite honestly, I thought this high-tech hodgepodge would come unglued. I envisioned a huge fireball. Out of the inferno, we'd see two streaks as Young and Crippen evicted themselves from the madness.

For heart-pounding seconds as Columbia and crew roared off into Florida-blue skies, I wanted Columbia to simply stop in midair and gently lower itself back down on the pad. It wasn't time to go — there had to be something that nobody had thought of!

But Columbia slipped out of sight. Sound engineering ruled the day. [Most Memorable Shuttle Missions]

Madman tiles

Not out of my mind during that first shuttle mission was the prospect of re-entry: the daredevil plunge back to Earth on those madman tiles!

Once on orbit, both the crew and the world saw missing bits of the thermal protection system. That promoted a high yikes factor. Like many reporters, I had been briefed about something called the "zipper effect" — that is, at re-entry one missing tile would lead to the dislodgement of the next tile, and so on.

So on April 14, 1981, I stood at Edwards Air Force Base in California, surviving the cold, early-morning desert sunrise and envisaging tragedy in the making.

My mood was soundly shaken by high-altitude booms as Columbia banked its way to a desert landing and wheels stopped. It seemed like only minutes later that Young and Crippen bounded out of the craft and headed for a public stage.

The moment was made even more electric as Young declared humanity was not too far away from reaching for the stars.

Definitely the future had arrived.

Pleasant surprise

Now fast forward to July 8, 2011. [Photos: NASA's Last Shuttle Mission in Pictures]

Shortly after Atlantis had bellowed its way into Earth orbit on the shuttle program's end-all mission, I sat down with Crippen to reflect on the milestone-making sojourn of Columbia. The interview session was arranged by the Coalition for Space Exploration, where Crippen serves as a board member.

"Overall, the pleasant surprise was that it worked as well as it did," Crippen told me. "We had planned for just about every contingency we could think of … and procedures for it. And we have very few to work. The whole system worked well."

Not that there weren't problems, Crippen pointed out. Among them, a balky toilet. There was the loss of an onboard recorder tied to data-gathering flight instruments. And there was a post-landing discovery that somebody had left a piece of packing plastic in an orbital maneuvering system tank.

"It could have clogged up the engine and caused us considerable problems in the deorbit burn," Crippen said. "There were some of those kinds of things. I'd classify them as nuisances … but some of them could have been critical."

And what about those wretched missing tiles?

"We didn't lose any on the bottom," only less-critical pieces of the thermal protection system that don't experience the blistering heat of re-entry, Crippen said.

How about those rumors that a U.S. military spysat snapped some calming close-up imagery of Columbia and its protective covering of heat shield blankets and tiles?

"That's still classified … can't say," Crippen said.

NASA enters the Twilight Zone?

As for the "Twilight Zone" that NASA appears to have entered in terms of the future, Crippen said the space agency talks about something out there, but it's not very clear.

"I think it's sad and a mistake to stand the shuttle down when we don't have another vehicle to take our people into space," Crippen said.

Being totally dependent on Russia is worrisome, he said, as is betting that commercial space providers will deliver as promised. "Which I'm all for … but I think that's going to take a while to mature beyond what we had hoped for," he added.

The Atlantis takeoff as the finale to the space shuttle program was also viewed here by noted space historian John Logsdon, professor emeritus of political science and international affairs at the George Washington University's Elliott School of International Affairs. After the 2003 explosion of Columbia, he served on the accident investigation board.

Watching Atlantis launch, "my main emotion was relief," Logsdon told me, "relief that the launch went off on time despite last seconds of drama … but more relief that the shuttle program is ending with the space station assembled, and NASA can finally focus on using the station and getting ready for new voyages of exploration."

Leonard David has been reporting on the space industry for more than five decades. He is a winner of this year's National Space Club Press Award and a past editor-in-chief of the National Space Society's Ad Astra and Space World magazines. He has written for SPACE.com since 1999.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years. Currently writing as Space.com's Space Insider Columnist among his other projects, Leonard has authored numerous books on space exploration, Mars missions and more, with his latest being "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published in 2019 by National Geographic. He also wrote "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet" released in 2016 by National Geographic. Leonard has served as a correspondent for SpaceNews, Scientific American and Aerospace America for the AIAA. He has received many awards, including the first Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History in 2015 at the AAS Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium. You can find out Leonard's latest project at his website and on Twitter.