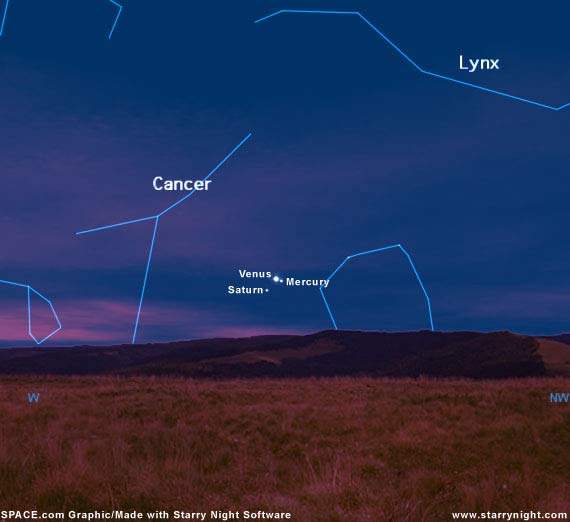

A spectacular gathering of three of the brightest planets will be the chief celestial attraction in the evening sky during this upcoming week. It will, in fact, be possible for anyone with a clear and unobstructed view of the west-northwest horizon to see three bright planets – Venus, Mercury and Saturn – in a single glance.

These three planets are destined to crowd into a small spot in the sky, making for a very distinctive and eye-catching formation that is sure to thrill most sky watchers. Think of it as "The Great Celestial Summit Meeting."

A wide variety of different conjunctions and configurations involving the planets typically occur during the course of any given year. It is rather unusual, however, when three or more bright planets appear to reside in the same small area of the sky.

From our Earthly vantagepoint, we can readily observe Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn with our unaided eyes as they revolve around the Sun. Each of these planets appears to move against the starry background at their own speeds and along their own tracks. It is obvious that since they are constantly moving at different speed, the positions of all five planets at any particular time is unique to that particular moment.

All of the naked eye planets – and the Moon as well – closely follow an imaginary line in the sky called the ecliptic. The ecliptic is also the apparent path that the Sun appears to take through the sky as a result of the Earth's revolution around it. Technically, the ecliptic represents the extension or projection of the plane of the Earth's orbit out towards the sky.

But since the Moon and planets move in orbits, whose planes do not differ greatly from that of the Earth's orbit, these bodies, when visible in our sky, always stay relatively close to the ecliptic line. Twelve of the constellations through which the ecliptic passes form the Zodiac; their names which can be readily identified on standard star charts, are familiar to millions of horoscope users who would be hard pressed to find them in the actual sky.

Ancient man probably took note of the fact that the planets – themselves resembling bright stars – had the freedom to wander in the heavens, while the other "fixed" stars remained rooted in their positions. This ability to move, seemed to have an almost magical, god-like quality. And evidence that the planets came to be associated with the gods, lies in their very names, which represent ancient deities.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The sky watchers of thousands of years ago must have deduced that if the movements of the planets had any significance at all, it must be to inform those who could read celestial signs of what the fates held in store. Indeed, even to this day, there are those who firmly believe that the changing positions of the Sun, Moon and planets can have a decided effect on the destinies of individuals and nations on the Earth.

Interestingly, five years ago, in May 2000, and again two years later in May 2002, several of the planets gathered together in the western twilight sky. In their advance – especially in 2000 and on much lesser scale in 2002 – there were numerous astrological predictions of earthquakes, floods, wars and other disasters. But despite all the ballyhoo, absolutely nothing happened.

Dr. Jean Meeus of Belgium, recognized as a world authority in spherical and mathematical astronomy, points out in his book, "More Mathematical Astronomy Morsels," that "such a gathering of three or more planets in a restricted area of the sky should really be called a 'grouping,' not 'an alignment.'" He goes on to point out that an "alignment" is when three or more planets and the Sun are on a straight line in space. However – strictly speaking – says Meeus, such an alignment never occurs, because three (or more) planets can never be exactly aligned.

Meeus has also defined the term "planetary trio" as when three planets fit within a circle with a minimum diameter smaller than 5 degrees. Your clinched fist held at arm's length, for instance, is equal to roughly 10 degrees; the pointer stars at the end of the bowl of the Big Dipper are separated by just over five degrees). "That limit of 5 degrees has been chosen more or less arbitrarily, but we have to make a choice."

From now through June 29, Venus, Mercury and Saturn will be a trio, all fitting within the prescribed 5 degree circle, the smallest circle (1.4 degrees) occurring on June 26 at 7 a.m. EDT.

Unfortunately, it is daytime at that particular time and the planets will be below the horizon for North America and Europe and hence unobservable. However, their rapidly changing night-to-night positions relative to one another should be most fascinating to watch.

The only drawback for prospective observers will be that these three planets will be visible for at best for only about an hour after sundown before they start getting too low to the horizon to be readily observable. While Venus (magnitude –3.8) and Mercury (magnitude –0.2) should be bright enough to see with the unaided eye in the twilight glow, Saturn (magnitude +0.2) will likely be more difficult.

Therefore, to avoid being disappointed, I would strongly suggest also using binoculars to scan low along the west-northwest horizon for the three planets, especially if it is rather hazy (as late June evenings often tend to be). Also during this time frame, you might also take note of the "Twin Stars," Pollux (+1.2) and Castor (+1.6) of Gemini, which will be positioned roughly 6 to 10 degrees to the right and slightly above the trio.

Here are some highlights for this upcoming week:

June 25: The three planets are arranged in the shape of a slender nearly isosceles triangle, pointing down and to the left, with Saturn at the vertex. The Mercury-Saturn side is 1.5 degrees long and the Venus-Saturn side is 1.3 degrees in length. Venus and Mercury are separated by just a half-degree (roughly the width of a full Moon). Venus and Saturn appear closest together relative to each other on this evening. Venus, however, appears 40 times brighter. Use binoculars to better catch Saturn through the bright evening twilight.

June 26: The triangle appears about half as wide compared with the previous evening, and now appears to be pointing almost straight down to the horizon. The Mercury-Saturn side is 1.5 degrees long and the Venus-Saturn side has increased slightly to 1.6 degrees in length. Venus and Mercury are now separated by less than 0.2 degrees (12-arc minutes) as seen from North America. To gauge just how close this is, the stars Mizar and Alcor, located at the bend of the handle of the Big Dipper are separated by a very similar apparent distance (11.8-arc minutes). If you have normal vision and a good, clear sky, you might be able to split Venus and Mercury without any optical aid, although keep in mind that Mercury will shine only 1/32 as bright as Venus.

June 27: Venus and Mercury will have an extremely close encounter with each other today. The two planets will appear closest together at 12:01 p.m. EDT, when they will be separated by a mere 3.88 arc minutes, or less than 1/8 of the apparent diameter of the Moon! Unfortunately, this happens during the daytime hours for both Europe and North America. Those living in the Middle East and Western Asia will be able to view the closest approach right after local sunset. Even though they will be slowly separating, both planets will still appear exceptionally close together at dusk from Europe (5 arc minutes), eastern North America (7 arc minutes) and western North America (9 arc minutes). Saturn meanwhile complacently sits just 2.5 degrees below Venus and Mercury.

June 29: The last evening all three planets can fit within a 5-degree circle. Venus and Mercury are still quite close, only about 0.6 degrees apart. Both planets are speeding away from the much slower-moving Saturn, now nearly 5 degrees below and to their right.

Saturn then becomes too deeply immersed in the solar glare to be seen, but Venus and Mercury continue to be visible into early July. Finally, on July 8 a skinny crescent Moon will be passing above these two planets, marking the end of the summit meeting.

Truly, that will be the icing on this celestial cake!

Basic Sky Guides

Full Moon Fever

Astrophotography 101

10 Steps to Rewarding Stargazing

Understanding the Ecliptic and the Zodiac

False Dawn: All about the Zodiacal Light

Reading Weather in the Sun, Moon and Stars

How and Why the Night Sky Changes with the Seasons

Night Sky Main Page: More Skywatching News & Features

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for The New York Times and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, New York.

| DEFINITIONS |

Degrees measure apparent sizes of objects or distances in the sky, as seen from our vantage point. The Moon is one-half degree in width. The width of your fist held at arm's length is about 10 degrees. 1 AU, or astronomical unit, is the distance from the Sun to Earth, or about 93 million miles. Magnitude is the standard by which astronomers measure the apparent brightness of objects that appear in the sky. The lower the number, the brighter the object. The brightest stars in the sky are categorized as zero or first magnitude. Negative magnitudes are reserved for the most brilliant objects: the brightest star is Sirius (-1.4); the full Moon is -12.7; the Sun is -26.7. The faintest stars visible under dark skies are around +6. |

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.