And then there were none.

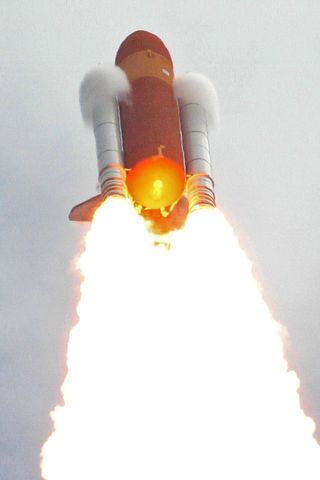

When NASA's final space shuttle mission touched down before dawn Thursday (July 21), you can bet the entire American astronaut corps was watching.

The final landing of shuttle Atlantis in Florida marked the end of the space shuttle era, and the United States will be unable to launch its own astronauts to space for the next several years.

But the American spaceflying corps, old and new, remains optimistic about NASA's new plan to focus on future deep space exploration while relying on Russian Soyuz spacecraft to ferry astronauts to and from orbit until private U.S. spaceships become available. [Photos of NASA's Last Space Shuttle Landing Ever]

Just before NASA's final space shuttle mission, the STS-135 flight of Atlantis, SPACE.com caught up with a handful of current and former astronauts to talk about the shuttle fleet's retirement and the future of American human spaceflight:

SPACE.com: How do you feel about the space shuttle program drawing to a close?

Cady Coleman (current astronaut; veteran of two shuttle flights, one station flight): Personally, I wish things were different. But I tend to work more on, "This is the way it is." The decision to retire the shuttle was made a long time ago. The decision to have this gap in American capability to launch people into space by ourselves was made a long time ago.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

We built the space shuttle, and we used it to build a space station. Now we have an orbiting space station, and people are working on it as we speak for over a decade. I'm excited about what we're going to do with it. I think we're in a pretty good place.

Jim Halsell (former astronaut; five shuttle flights): I came back from my first and also my subsequent flights with just a tremendous appreciation for [the shuttle's] capability.

The people who designed it had such an audacious perspective — we're going to build a vehicle, it's going to be the size of an airliner. It'll be big enough to take a Greyhound bus up to space and bring one back if we want it to. You can use the robotic arm to position something within a fraction of an inch of its desired position. You can do EVA's — spacewalks — and carry seven people comfortably for two weeks or even longer.

There will not be another vehicle, in my opinion, that combines that wide breadth of capability built in the remainder of our lifetimes. [NASA's Shuttle Program In Pictures: A Tribute]

I'm excited about the future. Certainly, like a lot of Americans, I'm disheartened by how large the [spaceflight] gap seems to have grown in the last few years. But I'm still optimistic about what will be eventually coming next, both in terms of the crew transport that is much safer than we've grown accustomed to with the shuttle, and also with the opportunity, with the heavy-lift vehicle, to move beyond low-Earth orbit.

Stephen Robinson (current astronaut; four shuttle flights): I think there's a big range between one extreme and the other. There are some common themes that we all feel, and one of them is pride. Pride that the American people built that space shuttle in the first place. And pride that we are retiring it after it accomplished its mission in full.

Terry Virts (current astronaut; one shuttle flight): Well, it's sad. I'd love to fly on the shuttle again. There's nothing better to do in life.

It's kind of tough right now, because we're losing so many people here at KSC [Kennedy Space Center] and JSC [Johnson Space Center]. They're really, really good people, and they love what they do. We have a really special workforce.

I just think of that. All the years of launching the space shuttle, and they made it possible.

Mike Massimino (current astronaut; two shuttle flights): I think we actually need to stop with this glum business. I mean, it's sad; people have lost their jobs. Hopefully we'll have something else that we can come up with, so all the people, all these talents that have been working on the shuttle for so long, can come back.

But I think we need to get this thing launched and landed and over with, and then move on to the next thing. [Giant Leaps: Top Milestones of Human Spaceflight]

I think having commerical companies involved is a good thing, because tax dollars can get rearranged, but if a company is making money, they're going to keep pushing forward. So hopefully those companies will be successful, and NASA will continue being funded and keep their exploring going.

I think we have a very good future, and I don't think we can actually see that until we get this thing launched and back.

Mike Fincke (current astronaut; one shuttle flight, two station missions): This is the closing of one page and the opening up of a new chapter of where humans are going. I'm looking forward to being part of that team.

SPACE.com: What's your best memory from your experiences aboard the space shuttle?

Massimino: Spacewalking on the Hubble Space Telescope, during STS-125. Easily. That's the highlight of my professional career.

Dan Tani (current astronaut; two shuttle flights, one station flight): There's a ton of them. There's too many good memories there to list.

Halsell: There are so many awe-inspiring moments involved in any shuttle flight. The liftoff is just as spectacular an event when you personally experience it as it is when you get to watch it. The noise, the vibration, the acceleration are all exactly as you might guess they would be.

My first view out of the window, on my first flight — we were approaching the coast of Africa after having launched, and I could look out the window and still see the coast of Florida. And there was a huge dust storm coming off of the Sahara Desert and making its way across the Atlantic Ocean right there to Florida. [Last Photos of Earth from NASA Shuttle]

I recalled that we'd been getting extremely red sunsets because of this phenomenon. And here I was, in the first few minutes of my first flight, and it was all at my feet. I was getting a geography lesson like no school had ever had the opportunity to give.

And it just goes from there. I could rattle on forever about the views. One thing you will never hear an astronaut come back and say is, "Well, that wasn't such a big deal." You will never hear that, I promise.

SPACE.com: How will people view the shuttle program 25 or 30 years down the road? What will its chief legacy be?

Massimino: The spaceship itself is really cool. It can take people, it can take cargo and it can bring stuff back. It launches like a rocket, it becomes a place to live and do experiments and do spacewalks from for a few weeks, and then it lands on a runway. It in itself has been a great technological accomplishment.

But what it's accomplished — three things come to mind. One, I'm very biased — the Hubble Space Telescope. Without the shuttle, you wouldn't have launched it, and you would not have been able to service it.

So I think its main scientific accomplishment has been Hubble. Its greatest engineering accomplishment has been building the space station. Incredible; I still can't believe the thing is actually built.

And then, I think on a global scale, it's gotten us to work with our international partners. We're friends now with the Russians, and we're working with them hand-in-hand. It's given us a chance to work internationally, diplomatically, with lots of other countries.

Tani: There are two things: space station and Hubble. Hubble wouldn't have been possible without the ability to go fix it, first, and then upgrade it. And we've done that. It's an amazing story, where we just take new cameras, new lenses, new sensors as the technology evolves.

And then the space station. Spectacular. We designed the space shuttle to go build a space station, and we've done that. We would not have been able to lift or assemble the space station without the shuttle.

Halsell: I think it'll be remembered for the technical capabilities that it combined. I think it'll be remembered as the vehicle that built the International Space Station, from which sprang a lot of hopefully breakthrough science discoveries — either life sciences or material sciences, or enabling our abilities to consider moving on out into the cosmos.

Virts: It was designed to let people work in space. And it's succeeded. It's made spaceflight routine.

It's allowed us to launch six or seven astronauts, allowed us to fix satellites, launch satellites, test out new technologies and do experiments. The biggest crowning achievement is building the space station. It really has been widely successful if you look at it from the point of why we built the space shuttle. It's done what it was supposed to do.

SPACE.com: If you were allowed to keep one piece of the shuttle as a souvenir, what would it be?

Robinson: I would say an INU, one of the navigational gyroscopes, because it's spectacular how accurate they are for 1970s technology. Yeah, I think that would be really, really cool. But then again I'm a real nerd.

Virts: What would I want? I'm a shuttle pilot, so I would go with a control stick.

Coleman: I would probably take one of the switches that was the deploy switch for the Chandra X-ray Observatory [Coleman was on the shuttle mission that deployed Chandra]. Or the one that was the big kill switch, which I used to regularly get my photograph taken with just to threaten the Chandra guys.

Massimino: I think I would like the control stick for the remote manipulator system, because I actually used that in space, and I come from a robotics background. That probably would be the most meaningful piece to me.

Tani: It'd be fun to have something small. There are covers — switchguards — on the C-3 panel, on the center panel between the commander and the pilot. It would be fun to grab one of those covers and have it on the desk.

Halsell: We used to use Hasselblad cameras to take pictures, which have a very specific noise. It was all very old and archaic and non-digital. But that was the sound of space, because in the background there was always somebody taking pictures.

So maybe I'd like to have one of those Hasselblad cameras. Maybe they'll give me one, because they don't use them anymore. They've all gone digital now.

Fincke: I can't think of one particular piece, because they all work so well together. It's an amazing machine.

SPACE.com: Can kids still grow up to be astronauts?

Virts: Well, there is still a space program. We just hired a new class, and those guys are just getting assigned to space station flights. So we are still flying to the space station — we just don't have a rocket to launch from America after STS-135.

Coleman: [Kids] don't need a space shuttle. They just need to know that space is there. I think if we can manage to find a way to bring the space station home to them — we should have a Today in Space, you know, a little thing, just to realize that you don't need to wait for a space shuttle to launch. People live there [on the space station]. Every day.

Massimino: Yeah, I think it is possible. The types of missions we're going to be doing might be a little bit different. But we're always needing new astronauts, and I think we're going to continue in the future as well.

Tani: Absolutely. I don't think it's a good career goal; it really isn't, because 99.9 percent of people will get disappointed. But it's a good direction to go, and it's a good thing to have on the horizon. So I certainly encourage them.

Halsell: I think absolutely so, because we're going to have even more astronauts stationed on the International Space Station. I suspect that once we get the transportation capability in place, we'll be swapping people out at three-month intervals as opposed to six-month intervals.

There are people like Mr. [Bob] Bigelow and his interest in building his own station, which I think has a lot of merit; I hope he continues to be successful.

So having those destinations, and then supporting them with an infrastructure of a variety of commercial and government transportation — I would say that the future's bright. The fact that we're ending the shuttle right now — while it is bittersweet for all of us who spent a lot of our career on it, it is in some ways going to enable us to take those next steps.

SPACE.com managing editor Tariq Malik contributed to this story. You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Visit SPACE.com for complete coverage of Atlantis' final mission STS-135 or follow us @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.