The discovery of a fourth moon around Pluto — which astronomers announced Wednesday (July 20) — is just the latest twist in the dwarf planet's convoluted story, one that's packed full of surprises and drama.

Pluto was once thought to be as big as the Earth. It was regarded as a full-fledged planet for three-quarters of a century, only to be demoted to a new category, "dwarf planet," in 2006. Pluto was not known to have any moons until 1978, and now scientists have found four satellites around the frigid, distant body — more than circle Mars, Earth, Venus and Mercury combined.

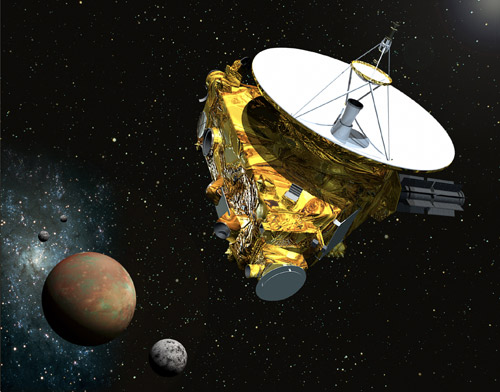

In short, scientists' understanding of Pluto, while improving, has always been fuzzy. And the picture likely won't really begin coming clear until NASA's New Horizons spacecraft makes the first-ever close flyby of the dwarf planet in July 2015.

"This is a whole new kind of planet," said New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern, of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colo. "It's going to blow our doors off." [Pluto: A Dwarf Planet Oddity]

Finding Planet X?

Pluto was discovered by American Clyde Tombaugh in 1930, as part of a search for the mythical "Planet X" that was thought to be perturbing the orbit of Uranus. Initial estimates of Pluto's size were off by a wide margin.

"It was presumed to be the size of Earth, and it was then reported as such," said Neil deGrasse Tyson, director of New York City's Hayden Planetarium.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The inaccuracy is understandable in many ways, because Pluto was difficult to detect in the early days, let alone study. The dwarf planet orbits 3.65 billion miles (5.87 billion kilometers) from the sun on average, about 39 times farther away than Earth does.

Over the years, estimates of Pluto's mass kept getting revised downward. But astronomers didn't get a good read on the dwarf planet's mass until 1978, when they discovered Pluto has a moon. This moon, named Charon, is more than half Pluto's size. [Photos of Pluto and Its Moons]

By studying the interactions between Pluto and Charon, astronomers were able to peg Pluto's mass at 0.2 percent that of Earth.

Hubble brings Pluto into view

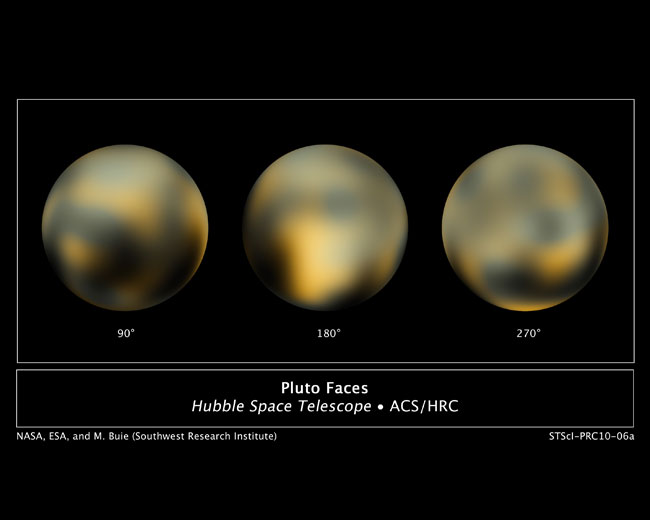

Pluto remained just a faint point of light until the 1990s, when NASA's Hubble Space Telescope imaged its surface for the first time. With these pictures, scientists learned that Pluto's surface is complex, harboring both light and dark areas.

"No one predicted that," Tyson told SPACE.com. "It has some of the highest brightness contrast of any objects in the solar system."

The 1990s also brought another sea change in astronomers' perception of Pluto: That it wasn't alone out on the edge of the solar system. Researchers began discovering other big, icy, Pluto-like bodies orbiting far from the sun.

"That was the real kicker," Tyson said. "It was clear that Pluto was just part of this whole other kind of family in the solar system."

This growing realization set the stage for the stripping of Pluto's planethood, but it took the discovery of an even more distant icy object to really get the wheels turning.

Pluto's demotion

In 2005, a team led by Caltech astronomer Mike Brown discovered Eris, which sits about twice as far from the sun as Pluto does. At the time, Eris was thought to be bigger than Pluto (they're now thought to be roughly the same size).

Eris' discovery ultimately led astronomers — uncomfortable with the prospect of finding many more planets in the frigid outer reaches of the solar system — to reconsider Pluto's status.

In 2006, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) came up with the following official definition of "planet": A body that circles the sun without being some other object's satellite, is large enough to be rounded by its own gravity (but not so big that it begins to undergo nuclear fusion, like a star) and has "cleared its neighborhood" of most other orbiting bodies.

Since Pluto shares orbital space with lots of other objects out in the Kuiper Belt— the ring of icy bodies beyond Neptune — it didn't make the cut. Instead, the IAU rebranded Pluto and Eris as "dwarf planets."

Dwarf planets are not considered full-fledged planets, so Pluto was stripped of the status it had held since its discovery in 1930. Eight planets officially remain in the solar system.

The decision was controversial, and it remains so to this day. Many scientists, including Stern, believe that the IAU's new definition is arbitrary, flawed and unscientific, and that it was drawn up chiefly to keep the official planets down to a manageable number.

While the debate continues over Pluto's status, the dwarf planet has kept getting more and more interesting.

An atmosphere, three more moons — and many discoveries to come

Studies have found, for example, that Pluto has an atmosphere. This tenuous gas layer, composed chiefly of nitrogen, carbon monoxide and methane, extends about 1,860 miles (3,000 km) beyond Pluto's surface — nearly one-quarter of the way to Charon.

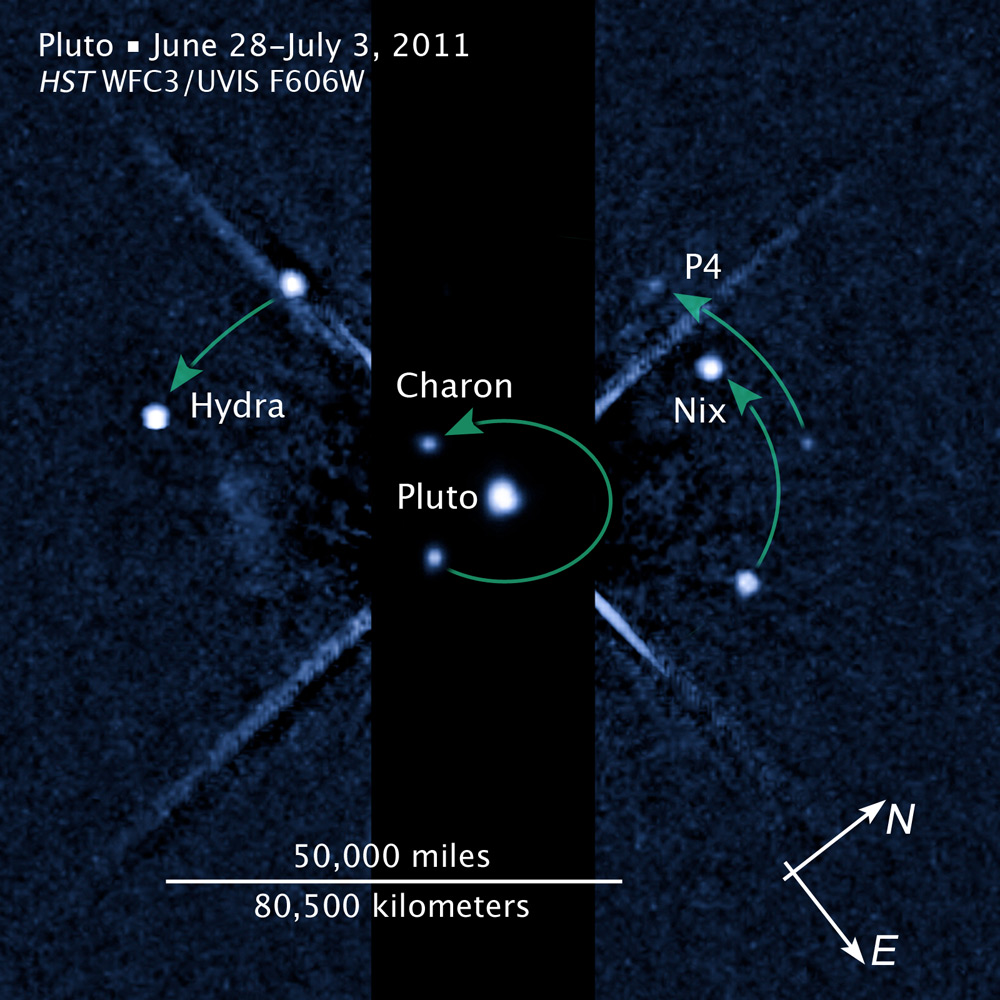

Further, in 2005, scientists using Hubble discovered that Pluto had two more moons, which they named Nix and Hydra. And just yesterday, Hubble observations detected the tiny fourth moon, which is being called P4 for now (although its final name may be Cerberus).

P4 is likely not the last surprise Pluto has in store for astronomers, Stern said. He expects the New Horizons mission to make many discoveries when it reaches Pluto four years from now and shines the first probing light on the distant, dark world.

"No one has ever been to an ice dwarf," Stern told SPACE.com. "It's going to write the textbooks — not even rewrite them, because there's nothing to write at this point."

And the knowledge gained about Pluto should help scientists learn more about the Kuiper Belt in general, which remains mysterious despite its large population of icy bodies. After it flies by the Pluto system, New Horizons is slated to study one or two other Kuiper Belt objects as well.

"We now know that there are more Kuiper Belt planets than giant planets and terrestrial planets combined," Stern said. "This is the dominant class of planets in our solar system, and we have not yet sent a spacecraft mission to them. So [New Horizons] is going to teach us a lot about a whole new class of world."

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.