NASA has attached its next spacecraft bound to explore Jupiter to the rocket that will launch the unmanned probe toward the gas giant next week.

Technicians wheeled NASA's Juno probe to its launch pad at Florida's Cape Canaveral Air Force Station this morning (July 27), then mated the craft to its Atlas 5 launch vehicle.

The event marked a key milestone for the $1.1 billion Juno mission, which aims to shed light on the origin and evolution of the solar system's largest planet. The rocket will launch Juno probe toward Jupiter on Friday, Aug. 5, mission scientists said.

"We're about to start our journey to Jupiter to unlock the secrets of the early solar system," said Juno principal investigator Scott Bolton, of the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, in a statement.

"After eight years of development, the spacecraft is ready for its important mission." [Photos: Jupiter, the Solar System's Largest Planet]

Closest-ever look at Jupiter

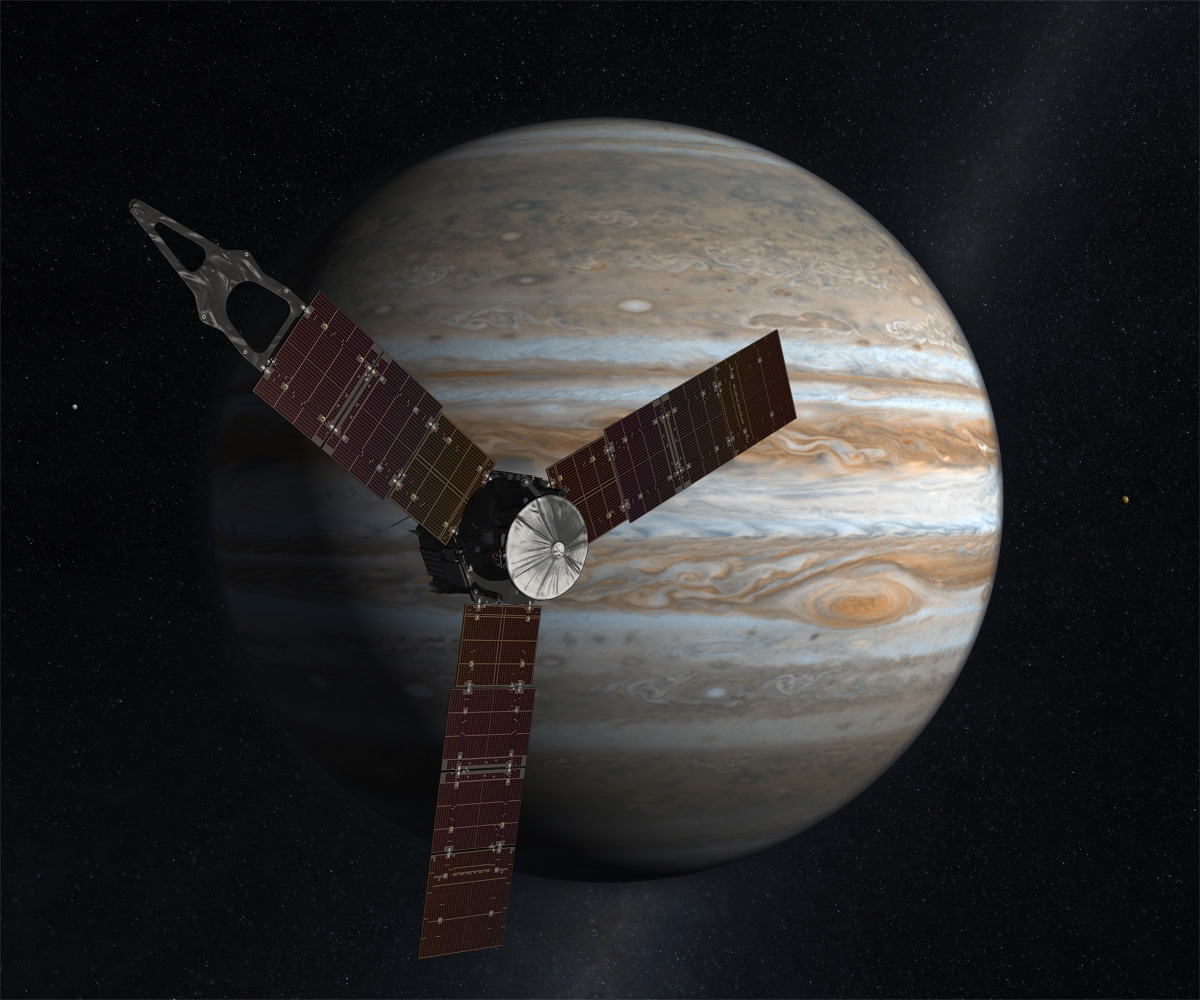

Juno will get closer to Jupiter than any other spacecraft in history — but not for a while. After its launch, the probe will cruise through the solar system for five years, finally arriving at the gas giant in July 2016.

Once there, Juno will undertake a year-long science campaign, studying Jupiter's structure, composition and magnetosphere, among other things, researchers said. The overall aim is to get a better idea of how, and when, the solar system's biggest planet formed.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Jupiter holds about twice as much mass as the rest of the solar system combined, not counting the sun. And it was the first planet to coalesce after the sun formed, gobbling up most of the dust and gas left in the early solar system.

That's part of the reason it's so interesting, according to Bolton. [Top 10 Extreme Planet Facts]

"If we want to go back in time and understand where we came from and how the planets were made, Jupiter holds the secret, because it's got most of the leftovers after the sun formed," Bolton told reporters today. "We want to know that ingredient list. What we're really after is discovering the recipe for making planets."

Juno will make a variety of observations in an attempt to determine that recipe.

For example, the spacecraft will measure the amount of water contained in Jupiter's thick, swirling atmosphere. Relatively large amounts of water might suggest that Jupiter first formed farther out in the solar system, then migrated into its present position, Bolton said.

And scientists still aren't sure if Jupiter has a solid core of heavy elements, or if it's made entirely of gas. Juno will look into that question as well, by measuring Jupiter's magnetic and gravity fields.

"Juno's prepared to be able to help constrain those answers, and help provide that information so that we can discriminate among models of how Jupiter formed and, in fact, what the history of our early solar systemwas," Bolton said.

An armored tank of a spacecraft

Juno will settle into a highly elliptical polar orbit around Jupiter in 2016, coming as close as 3,107 miles (5,000 kilometers) from the gas giant's cloud-tops.

This proximity will afford great looks at the giant planet, but it's dangerous for Juno, too. Jupiter possesses the strongest radiation environmentof any solar system body beyond the sun. So mission planners have encased Juno's sensitive instruments and electronics inside a titanium "vault" for protection.

"We're basically an armored tank going to Jupiter," Bolton said.

Jupiter's strong radiation also dictated the particulars of Juno's orbit, requiring mission managers to slot the spacecraft precisely between several dangerous belts on its laps around the planet.

"This is like threading a needle," Bolton said. "We're going right through the only safe haven."

Juno weighs about 8,000 pounds (3,627 kilograms), but about half of that is fuel, researchers said. For power, the spacecraft relies on three huge solar arrays, each the size of a tractor-trailer.

The arrays' 18,698 solar cells will generate about 400 watts of power out at Jupiter, which sits about 400 million miles (644 million km) farther from the sun than Earth does. Out there, sunlight is 25 times less intense than it is here on our home planet.

Juno will make 33 orbits of Jupiter over its year-long operational life, then be crashed intentionally into the giant planet. Researchers want to make sure Juno doesn't slam into — and contaminate — any of Jupiter's moons, some of which scientists think may be capable of supporting life.

But the mission's end is far off in the future, as are the beginnings of its observations at Jupiter. For now, the mission team is looking forward to just getting the spacecraft off the ground.

"It's really exciting," Bolton said. "We're just a few days away from our launch."

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcomand on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.