Driving on the Moon: The 40-Year Legacy of NASA's First Lunar Car

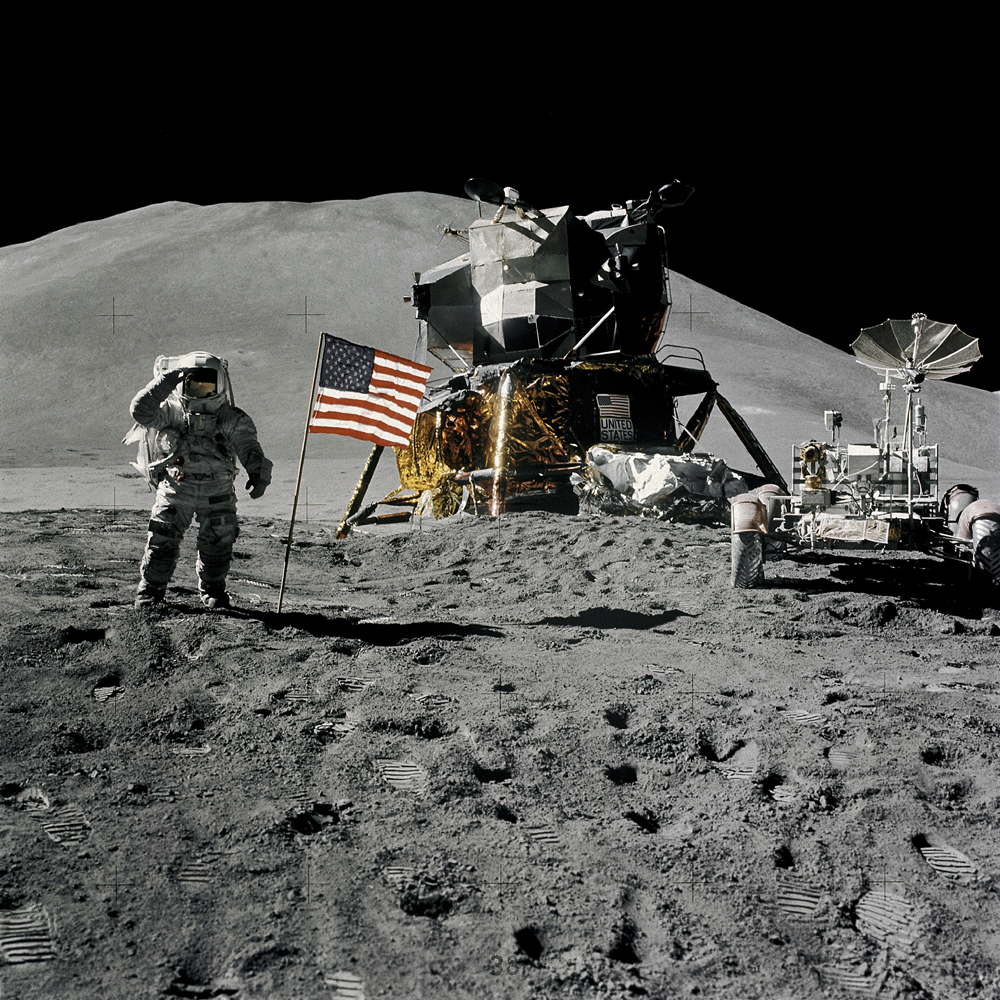

When NASA's Apollo 15 astronauts David Scott and James Irwin touched down on the moon 40 years ago, they had an extra special tool packed away on their lunar lander: a dune buggy-size rover that enabled them to become the first humans to drive on the surface of a world beyond Earth.

Rover technology has made great strides since Scott and Irwin landed on the moon on July 30, 1971, but the lessons learned from NASA's first Lunar Roving Vehicles (LRVs) are still applicable today. While technology has evolved since the Apollo era, NASA's first rovers are influencing manned and robotic vehicles for exploration on Mars and beyond.

"The LRV on Apollo fulfilled a very important need, which was to be able to cover large traverses, carry more samples, and get more scientific exploration done," Mike Neufeld, a curator in the space history division at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. told SPACE.com. "It was a really important part of why Apollo 15, 16 and 17 were so much more scientifically advanced and productive." [Photos: The Evolution of NASA's Moon Cars]

Driving on the moon

Apollo 15 was the fourth mission to land men on the moon, and it was the first of three missions to use the LRVs. The rover had a mass of about 460 pounds (208 kilograms) and was designed to fold up so it could fit inside a compartment of the Lunar Module.

"It was a very elegant little vehicle," Neufeld said. "It had to be lightweight and had to be folded up in a very compact space. They were very successful – there were no major failures – so clearly it was a successful design." [Video: NASA's 21st Century Moon Ride]

And they drove relatively well, Neufeld said, given the rocky terrain on the moon. The rovers could reach a top speed of about 8 mph (about 13 kph), but the moon's cratered surface prevented the astronauts from driving too fast.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"They weren't driving on flat land – it was more like a dirt buggy than anything else," he explained. "It didn't travel that fast, but for the astronauts who drove it, it seemed like it was exciting and fast. It was a pretty bouncy ride. Even flat looking terrain on the moon is not very flat because there are so many crater pits, so it would have been a fairly exciting ride."

The lunar rovers also injected a new level of public enthusiasm for the Apollo program.

"Overall public interest had declined after Apollo 11," Neufeld said. "The public was becoming more and more blasé. Apollo 15 provided a blip upwards in public interest. Part of it was because the landing site was so much more attractive, and there were also more television broadcasts from the moon. But, the rovers were definitely a part of that. The public took a lot of interest in this new capability that the astronauts had."

The LRVs allowed the Apollo astronauts to explore beyond their landing site, but there were definite limitations, such as the non-rechargeable battery life of the rovers. As a safety precaution, the vehicles were also constrained to a distance that, if the rover broke down, the astronauts would have enough resources in their life support systems to walk back to the Lunar Module.

On the Apollo 15 mission, the LRV was driven a total of about 17 miles (27 km), which amounted to 3 hours and 2 minutes of driving time, according to NASA officials.

Moon rover legacy

In the decades since the end of the Apollo program, engineers have looked to the LRVs for cues on how to develop current and future manned and robotic rovers. [Coolest Vehicles You'll Never Get to Ride]

At NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, Calif., engineers collaborated with Apollo-era designers to develop the vehicles for the Mars Pathfinder project. Even though past and current Mars rovers were designed to be robotic, studying the first manned lunar vehicles proved invaluable, said Kobie Boykins, an engineer in JPL's spacecraft mechanical and engineering division.

"There was a lot of information that we learned," Boykins told SPACE.com. "We watched videos and saw how the NASA astronauts drove around on the rover. All the basic physics of how we interact with the soil stays the same even without having a human being in the rover. It helped us understand our capabilities and our limits. We needed to then figure out how to drive over rocks and drive on steeper inclines, but it's all applicable."

Boykins and his team worked on the twin Spirit and Opportunity rovers, which landed on Mars in January 2004 and have greatly outlasted their planned three-month lifespan. Spirit, which got stuck in sand, was declared dead by its operators earlier this year, but Opportunity is still driving steadily on the surface of the Red Planet.

In addition to being robotic, the Mars rovers differed from the Lunar Roving Vehicles because they drove at a much slower pace – about 2 inches per second (5cm/s).

"It's about the land speed of a Galapagos turtle," Boykins said. "There were a lot of design ideas that came from the Apollo days, but the lunar rovers were orders of magnitude faster."

Future space car tech

Boykins is also working on NASA's newest Mars rover, a car-sized robotic explorer named Curiosity, which is scheduled to launch into space in late November. But NASA teams are also involved in developing other rovers, ones that could eventually be driven by humans once again on the surface of the moon or Mars.

The Space Exploration Vehicle (SEV) looks like a luxury RV compared to the more primitive-looking lunar rovers, but the Apollo program definitely put its stamp on this next generation vehicle, said Lucien Junkin, an engineer with the SEV project at NASA's Johnson Space Center.

The SEV engineers worked closely with Harrison Schmitt to design and test the new vehicle, which features an enclosed, pressurized cabin, 12 wheels and mounted spacesuits on the back. Schmitt, a former NASA astronaut, drove one of the original lunar rovers during the Apollo 17 mission, the final flight that rounded out the Apollo space program.

"We wanted to take all the lessons learned from the Apollo and Mars rovers and combine all that together, but also challenge conventional wisdom," Junkin told SPACE.com. "With the SEV, we built what we call a feature-rich vehicle, so things like cargo, space and other creature comforts. We wanted to keep it simple but move it forward."

The SEV is designed to comfortably carry a two-astronaut crew on multiple day excursions. The vehicle was originally designed as part of the now-canceled Constellation program that was going to return astronauts to the moon. The engineering team is now designing and testing the vehicle to be compatible with future missions that could require rovers either on the moon or Mars, Junkin said.

"We have to stay away from the policy and keep our nose to the grindstone," he said. "We want to keep developing a rover that is in America's garage, so when it's time for us to go to another heavenly body or another planet, America will be ready with a vehicle."

You can follow SPACE.com staff writer Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Denise Chow is a former Space.com staff writer who then worked as assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. She spent two years with Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions, before joining the Live Science team in 2013. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University. At NBC News, Denise covers general science and climate change.