Five years ago today (Aug. 24), Pluto was demoted from full-fledged planet to a newly created category, "dwarf planet."

The International Astronomical Union made the official call. But if any one person can be held responsible for Pluto's "death," it's probably Caltech planetary scientist Mike Brown.

Brown led the team that discovered Eris, a frigid world circling the sun far beyond Pluto, in 2005. Eris was initially thought to be larger than Pluto, and the find helped spur astronomers to redefine just what a planet is. Indeed, Brown wrote a book about Pluto's reclassification called "How I Killed Pluto and Why It Had It Coming" (Spiegel & Grau, 2010). [Pluto's Planet Title Defender: Q & A With Alan Stern]

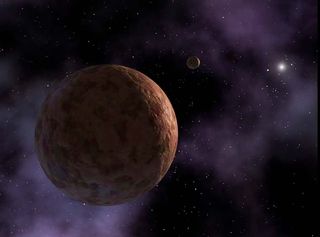

Brown continues to search for objects in the frigid outer reaches of the solar system. He's found other dwarf planets in the Kuiper Belt, the ring of icy bodies beyond Neptune. He also discovered something even farther away — a mysterious object called Sedna, whose highly elliptical orbit takes it up to 84 billion miles (135 billion kilometers) from the sun at its most distant point.

As the fifth anniversary of Pluto's demotion neared, SPACE.com caught up with Brown to chat about that controversial decision, dwarf planets and what we're learning about the outer solar system.

SPACE.com: How do you feel about Pluto's demotion now, five years later? Was it the right move?

Mike Brown: Five years is a good amount of time to sit back and reflect. Five years ago, everyone was standing up and saying, "This will never stand. The public will go crazy. This will never appear in books."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

And five years later, pretty much everyone just accepts it. It's just the way that the solar system is now. In the end, people are willing to listen to what you have to say, and, if you have a good reason for it, willing to go along. It's a good reminder to all of us, I think.

SPACE.com: Part of the reason people are getting onboard is that scientists keep finding more and more big bodies out there in the Kuiper Belt.

Brown: I made up a list last week, just because I was curious myself, of how many objects are big enough to consider probably dwarf planets. We don't know for sure, because it's hard; we don't know the sizes of all of these, and we don't know exactly how big you have to be to be round.

But I had 107 "probably" dwarf planets and 428 "possibly" dwarf planets. [Meet the Solar System's Dwarf Planets]

SPACE.com: Wow. That's a lot bigger list than people are used to dealing with.

Brown: Yeah. And some people will say, "Well, gee, there's nothing wrong with calling all those planets. What's wrong with having 110 planets?"

And the answer is, you're really missing a big distinction between these different types of things if you mush them all together into one category. These other 428 objects behave very differently than the eight big ones.

So I actually think it's been really good. Even five years later, people still care enough to ask why, if they were sort of asleep five years ago. And it has continued to be, I think, just a fantastic teaching opportunity.

People often say it's good to see how science works, and that science changes with new evidence, which is also good. If Pluto had stayed a planet and everybody had just gone on their merry way, then no one would realize that our concept of the solar system was actually wrong, and gotten this new concept.

So I think people are coming to it. It's been fun to watch.

SPACE.com: Why do people get so worked up about Pluto and its status? Why do they care so much?

Brown: My theory is that it feels like part of the neighborhood. If you ask someone about where they live, they can describe their neighborhood, they can describe their city, they can describe their continent, they can describe the Earth, they can describe the solar system — and that's it. [Infographic: Pluto: A Dwarf Planet Oddity]

Everybody knew the nine planets. That was their touchpoint for what their local neighborhood is. And taking one away is a dramatic change in their mental image of their biggest view of the cosmos. Even though it shouldn't have been there, even though we've found many others, it just messes with their mental concept, and I think that can be very disturbing for people.

I do think that the Disney dog made a big difference, too. That just increases the affection for this thing called Pluto.

SPACE.com: Is it important what we call Pluto, whether it's a planet or a dwarf planet? Are these names important?

Brown: I think a lot of people will say, "It's just semantics. It doesn't matter what we call them." And I disagree entirely. I actually think it matters a lot.

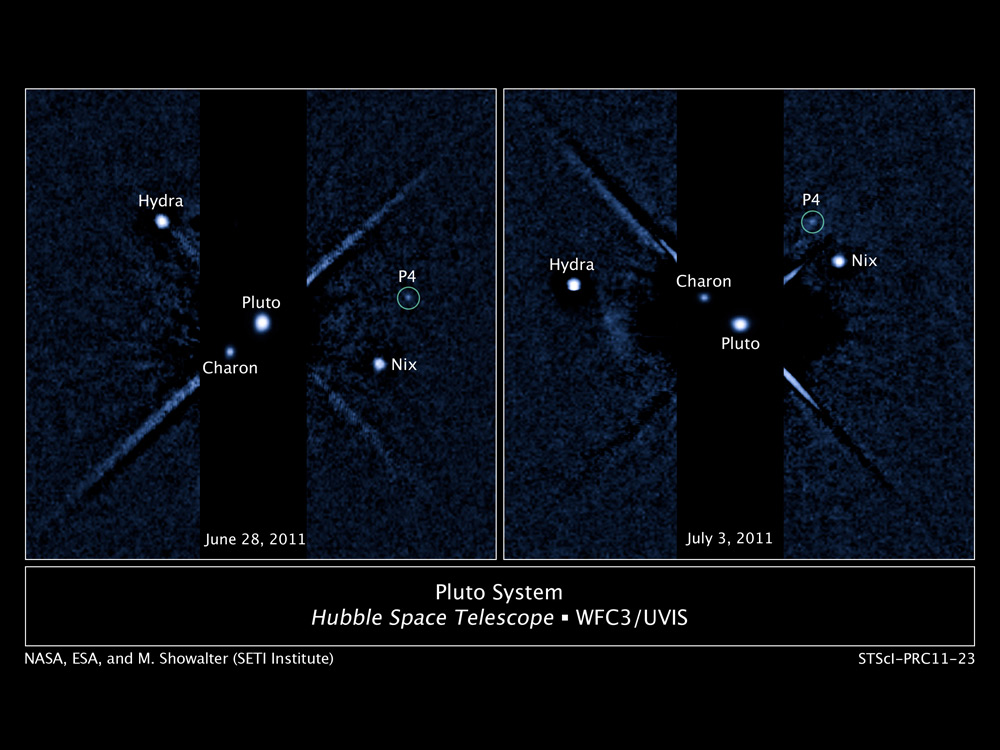

I don't care what the specific word is — you can make up any word you want. But it's classification that matters. Classification is the first step toward understanding. If you mess up the most basic classification of the whole solar system by not noticing the difference between the eight large planets and everything else — if you miss that, you've kind of missed the solar system. [Photos of Pluto and Its Moons]

So I think it matters a lot. It's also the main way that we teach people about the solar system — through the word "planet." And if we don't get that right, I don't think we can complain when people don't understand science and the solar system.

SPACE.com: If that's the case, then should we further subdivide the planets, calling some of them rocky planets, for example, and some of them gas giants?

Brown: Well, we do. We talk about terrestrial planets and giant planets. That's the second-order thing. Once you get the first order — that these are the planets — then I think people who want to explore more very quickly get the terrestrial planets and gas giants.

SPACE.com: What's the legacy of Pluto's demotion, and the new classification of the solar system, going to be?

Brown: I really do think that people are going to look at this and say, "Wow, it is so obvious that that's the right choice. What was the argument? What was going on?" Everybody will just chuckle a little bit and say, "Those crazy 21st-century people."

In the end, I hope that it leads to a richer understanding and more interest in all of the dwarf planets and all of the outer solar system, and how it works. It's a big, fascinating part of the solar system. And if you think about it as just Pluto and nothing else out there, you really have missed something cool about the solar system.

SPACE.com: As we discover more and more of these objects, what are we starting to learn about the outer solar system, and what lies beyond Pluto?

Brown: What I think we've learned, which has been just fantastic, is that we now have enough objects that are of a similar size to Pluto that we can start to compare them.

When there's just one of something, it's very difficult to understand it on a general level. Now we have Pluto, we have Eris, we have Makemake, we have Sedna and Quaoar. All of these things have their own little interesting twists that teach us generally how these dwarf planets behave — what their atmospheres do, what their interiors do.

We have gone from nearly complete ignorance about these sorts of bodies to an incredible richness, and trying to understand how they function as little worlds of their own.

SPACE.com: What do you think the next five or 10 years are going to bring? Do you think we're going to start getting a handle on how these objects behave, how they were made and where they came from?

Brown: I do think so. The main pulse of discovery of these large objects in the outer solar system sort of is past. We've in a sense surveyed most of the Kuiper Belt for the largest of the objects. There'll still be a few here and there that we may have overlooked.

But in the Kuiper Belt itself — where Pluto is, where Eris is — there probably won't be any other real large objects. So we've been spending the last five years in that region, studying the ones we've found. Before, we were really just running around trying to find as many as we could. Now we're really trying to understand.

But the "running around, trying to find as many as we can" has now expanded out to this region beyond the Kuiper Belt. And these days, there's one lone object sitting out there, Sedna, which is sort of like the Pluto of the next outer solar system, in the sense that it was the first one found. And for a long time, we haven't found any others.

Now, in Pluto's case, it was 60 years before we found any more. In Sedna's, I hope it doesn't take 60 years. We know there are other things like Sedna out there.

They've been extraordinarily hard to find. But we are continuing to beat the sky as hard as possible to see if we can find these things. And that I think is going to be where the next big discoveries are going to be made.

SPACE.com: What do you think is going on with Sedna? Where did it come from, and why is its orbit so weirdly elliptical?

Brown: We have some very precise information [about Sedna]. We have its very precise orbit, and it's telling you something incredible. It never comes close to a giant planet, which means it did not get placed in that orbit by a giant planet. And yet it had to have been placed in that orbit by something.

So the zeroth-order piece of information is that, somewhere out there, something perturbed Sedna, and that thing is no longer there. Now, that thing could've been another planet; it could have been a star that came close to the sun; it could have been a lot of stars, if the sun was born in a cluster.

Somewhere in Sedna's history, it tells you about the formation of the sun and the history of the sun, and there's clearly information there. But here's the problem when you only have one [object like Sedna]: You don't know which of these many different ideas could be true.

You don't need to find very many more. If you could find three or four or five — even those would be an order of magnitude increase in our knowledge of how these things got out there.

SPACE.com: Do have a guess as to how many dwarf planets are actually out there?

Brown: When we survey the whole sky, I would predict that there will probably be twice as many as we know now. I'm going to say two or three hundred "probablys" and a couple thousand "possiblys" in the Kuiper Belt.

Now, if we can ever find what's going on in this region where Sedna is, and if it's as occupied as we think it might be, it may well have five to 10 times more objects there even than in the Kuiper Belt. So that'd be another 10,000 or 20,000 "possiblys."

It's really cool that there are that many out there. In the other definition of planet, all 20,000 of these would be planets. And that is kind of silly, if you ask me.

If you said that there are eight planets and then a kajillion dwarf planets, that's a pretty good description of what the solar system's actually like. If you said, "Wow, we've got this planetary system and there are 20,000 planets. Oh yeah, and eight of them are significantly bigger than all the rest of them" — it's not a very useful classification.

As long as you only get one shot at a word to describe the solar system, I vote for the one that most profoundly and succinctly describes how we'd like to tell you what the solar system is about.

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.

Most Popular