Greatest Mysteries: Where is the Rest of the Universe?

Scientiststrying to create a detailed inventory of all the matter and energy in thecosmos run into a curious problem--the vast majority of it is missing.

"Icall it the dark side of the universe," said Michael Turner, a cosmologistat the University of Chicago, referring to the great mysteries of dark matterand dark energy.

In fact,only 4 percent of the matter and energy in the universe has been found. Theother 96 percent remains elusive, but scientists are looking in the farthestreaches of space and deepest depths of Earth to solve the two dark riddles.

Missingmatter

Einstein'sfamous equation "E=mc^2" describes energy and matter (or mass) as oneand the same--maps of the cosmos refer to the energy-matter combination asenergy density, for short. The problem with detecting dark matter, thought tomake up 22 percent of the universe's mass/energy pie, is that light doesn'tinteract with it.

But it doesexhibit the tug of gravity.

Initialevidence for the mysterious matter was discovered 75 years ago whenastrophysicists noticed an anomaly in a jumble of galaxies: The galacticcluster had hundreds of times more gravitational pull than it should have, faroutweighing its visible mass of stars.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Wecan predict the motions of the sun and planets very accurately, but when wemeasure distant things we see anomalies," said Scott Dodelson, anastrophysicist at Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory in Illinois. "Darkmatter is currently the best possible solution, even though we've never seenany of it."

Anotherhallmark of dark matter is gravitational lensing, similar to the effect oflight passing through a piece of polished glass. Massive objects like the suncan bend light, but colossal clouds of dark matter create"bubbles" in the cosmos that magnify, distort and duplicate thelight of galaxies or stars behind them.

Gravitationallensing recently exposed evidence of the unseen mass in the Bullet cluster aswell as ina ring around a cluster of colliding galaxies called ZwCl0024+1652.

Particlehunt

In spite ofthe ghostly evidence, pieces of dark matter have yet to be pinned down byresearchers. "Until we actually discover particles, we're not homeyet," Dodelson said.

Particlephysicists have detected neutrinos, which are extremely lightweight particlesthat pour out of the sun and hardly interact into ordinary matter, but Turnersaid they make up an extremely small fraction of dark matter in the universe.

"Wearrested one of the members of the gang, but not the leader of the gang,"Turner said of neutrinos. He thinks the leader is actually a WIMP: a weaklyinteractive, massive particle. Unfortunately, WIMPS are just a theory sofar.

Thethinking goes that WIMPs are very heavy, yet like neutrinos they rarely bumpinto matter to produce a detectable signal. But the idea that WIMPS--such astheoretical axion or neutralino particles--can bump into visible matter at allgives scientists hope.

"Thisis a story that may soon be at its end," Turner said, noting that theCryogenic Dark Matter Search in the Soudan mine of Minnesota and otherexperiments below the ground should be sensitive enough to detect a WIMP.

Theanti-gravity

Perhaps thebiggest mystery of all is dark matter's big cousin, dark energy.

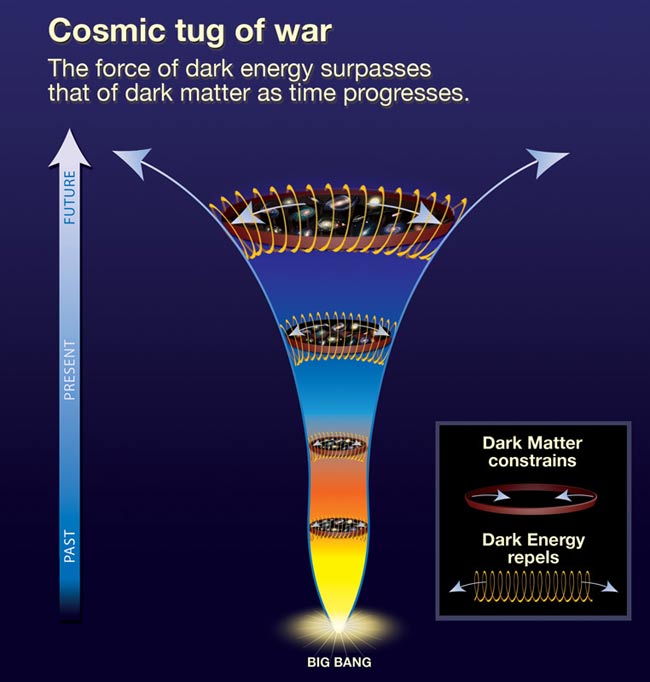

Theinvisible force is thought to be a large-scale "anti-gravity,"pushing apart galactic clusters and causing the unexplainable, acceleratingexpansion of the universe. Turner thinks dark energy is the biggest mystery ofthem all--and quite literally, since physicists predict that it makes up 74percent of energy density in the universe.

"Sofar, the greatest achievement with dark energy is giving it a name,"Turner said of the elusive force. "We are really at the very beginning ofthis puzzle."

Turnerdescribed dark energy as "really weird stuff," best thought of as anelastic, repulsive gravity that can't be broken down into particles. "Weknow what it does, but we don't know what it is," Turner said.

Whileastrophysicists look deep into space to gather more details about darkenergy's effects, Turner noted that theoretical physicists are focusing onexplaining how the force actually works. And at this point, he joked, anyphysicist's explanation for dark energy is probably good enough to consider.

"We'reat this very early stage, at the crime scene of dark energy's existence, if youwill," Turner said. "It's a highly creative period, and now is thetime for ideas."

- Another Great Mystery: What Happens Inside an Earthquake?

- VIDEO: Dark Matter Ring Discovered

- The Top 10 Strangest Things in Space

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Dave Mosher is currently a public relations executive at AST SpaceMobile, which aims to bring mobile broadband internet access to the half of humanity that currently lacks it. Before joining AST SpaceMobile, he was a senior correspondent at Insider and the online director at Popular Science. He has written for several news outlets in addition to Live Science and Space.com, including: Wired.com, National Geographic News, Scientific American, Simons Foundation and Discover Magazine.