Hubble Telescope Videos Show Baby Stars Spewing Violent Jets

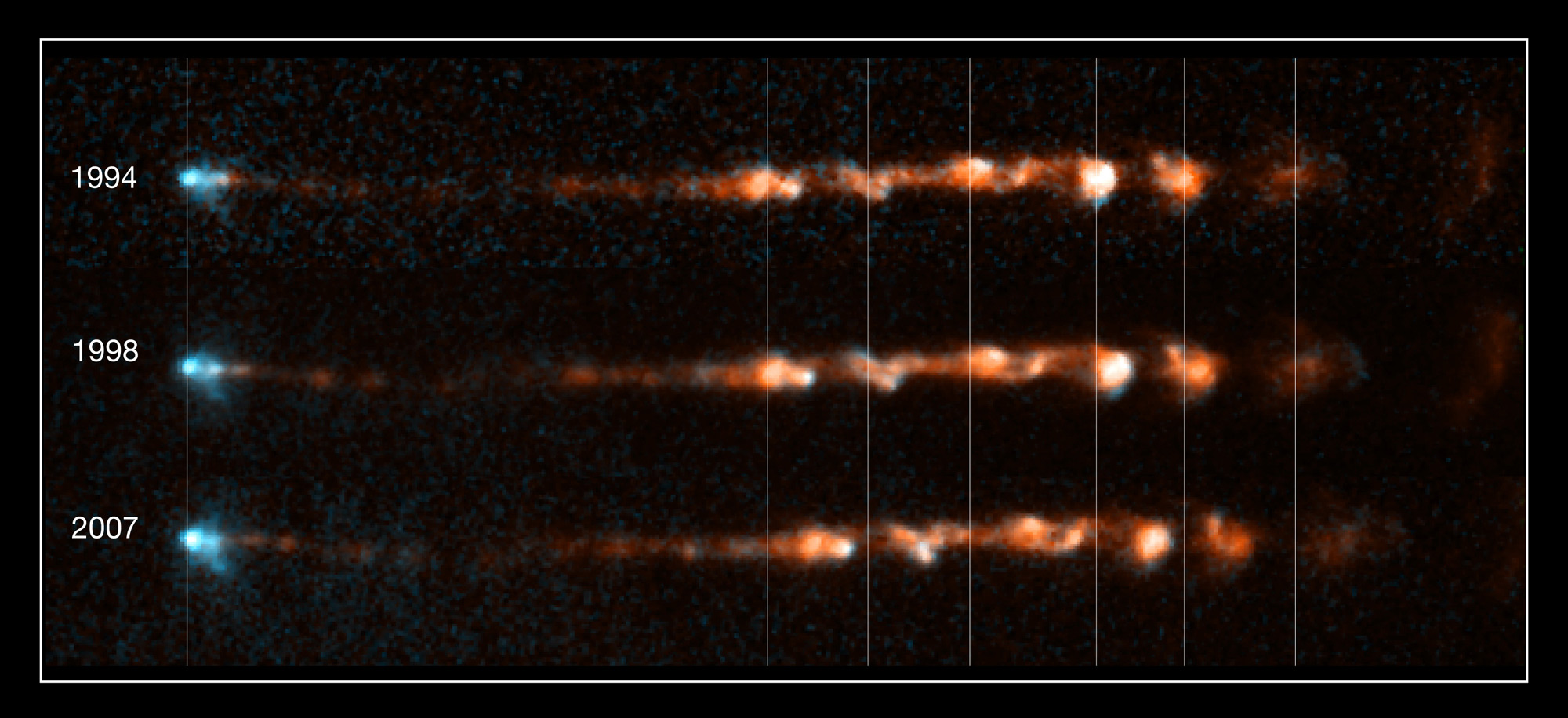

New details about the violent birth of new stars are revealed in a series of movies compiled from 14 years' worth of Hubble Space Telescope observations.

The videos stitch together pictures of nascent stars at various periods to present continuous-motion views of how stars are born. They reveal, in particular, how high-speed jets from baby stars can spew out matter in two beams that fizzle out over time.

Researchers hope to use the videos to build a better picture of how stars like the sun come to be. [See the new Hubble videos of baby star jets]

A star is born

Stars form when clouds of cold hydrogen gas condense under gravity, pulling together until the material is hot and dense enough to ignite nuclear fusion burning. The budding star's gravity continues to attract more matter to it, which settles around the star in the form of a disk.

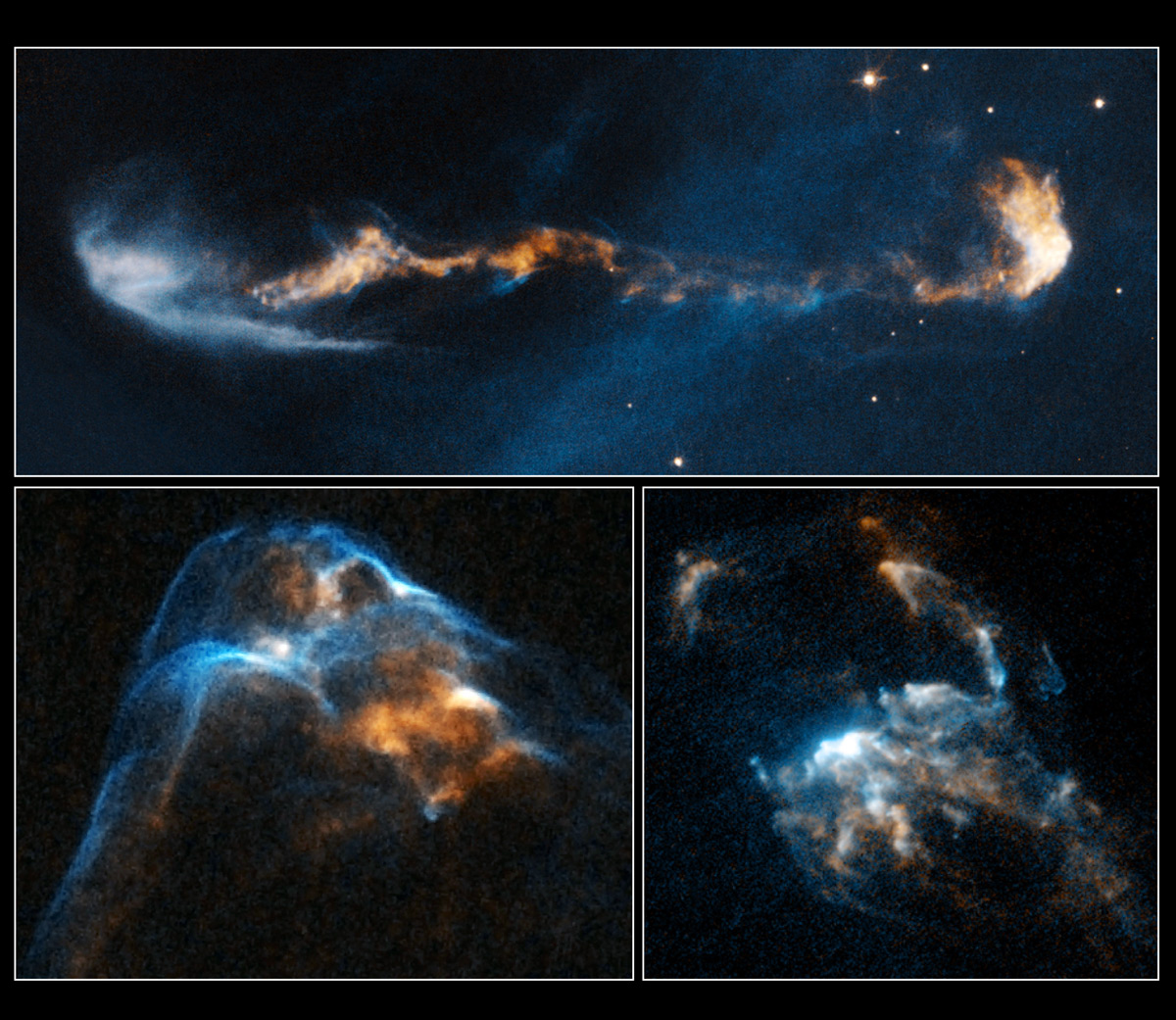

Often gas and dust in the disk condenses to form planets that continue to orbit the star. But some of the disk's material can also be pulled back in toward the star and flung outward in the form of two jets aligned with the star's spin axis.

How these jets form and change over time has been a mystery, but the videos show jets around three particular stars at various points over a period of years, providing a chance to see them evolve for the first time. [Hubble's Most Amazing Discoveries]

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Clumpy streams

The jets in the videos extend about 10 times the width of the solar system and contain material speeding faster than 435,000 miles per hour (700,000 kilometers per hour).

Among the revelations is the fact that matter does not seem to spew out in a constant flow from the stars' jet pairs, but rather pumps out in clumps. These clumps stream at different speeds, with the faster blobs running into the slower ones to create glowing waves of heated material called bow shocks, the videos show.

"Taken together, our results paint a picture of jets as remarkably diverse objects that undergo highly structured interactions between material within the outflow and between the jet and the surrounding gas," said Rice University astronomer Patrick Hartigan, the study's leader, in a statement. "This contrasts with the bulk of the existing simulations which depict jets as smooth systems."

Piecing pictures together

Hartigan and his colleagues created the videos by combining Hubble data of three different baby stars each around 1,350 light-years from Earth. The data come from observations made on Hubble's Wide Field Planetary Camera 2 between 1994 and 2008.

The researchers hope the knowledge they've gained will help refine computer simulations that attempt to calculate the complex processes going on in the stars and their environs as they form.

"For the first time we can actually observe how these jets interact with their surroundings by watching these time-lapse movies," Hartigan said. "Those interactions tell us how young stars influence the environments out of which they form. With movies like these, we can now compare observations of jets with those produced by computer simulations and laboratory experiments to see which aspects of the interactions we understand and which we don't understand."

The results of the study are reported in the July 20 issue of the Astrophysical Journal.

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.