A Temporary Triangle, and Reader Responses

Editor's Note: Below, Joe discusses a temporary triangle you can see in the night sky.

A couple of weeks ago, I discussed the possible origin of the famous Summer Triangle. Just who was the first person to assign that name to the large and bright pattern formed by the stars, Vega, Altair and Deneb?

After doing some research, I concluded that it was Hans Augusto ("H.A.") Rey who first popularized the Summer Triangle moniker through his two widely circulated star guides, "Find the Constellations" and "The Stars -- A New Way to See Them."

I then asked SPACE.com readers to write in and see if they could help solve the mystery. Since "Summer Triangle" first appeared in Rey's 1954 "Find the Constellations" book, I asked if anyone could specifically point to a reference source prior to 1954 that coined the term.

In the days that followed I received quite a few interesting replies.

A navigators' triangle?

Peter Kelley of St. Paul, Minnesota wrote in to suggest that early almanacs, ship logs, and early agricultural records be researched, "...to see if this set of stars were used in those professions."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Thomas F. Divine of Smyrna, GA also chimed in, asking, "Have you looked in books more related to navigation than astronomy? For example, one of my all-time favorites is the 'American Practical Navigator' by Bowditch." (As it turns out, this publication does make reference to the Triangle formed by Vega, Deneb and Altair, but not as the Summer Triangle).

Still, some other (more obscure) navigational manuals might yet hold a clue.

Steve Bilanow of Columbia, Maryland wrote,

"I remember hearing reference to the "Summer Triangle" back in the sixties (when I was a teenager) from someone who had been a navigator for U.S. bombers during World War II. He referred to it as a lifesaver for navigation reference. Therefore I wonder if the term was popularized through U.S. navigator training during World War II."

Gregg Ruppel of Ellisville, Missouri noted that,

"One summer evening in 1958 (as I recall) my father pointed out a satellite passing through the Summer Triangle. When I asked him what that was he explained that it was a group of three navigational stars taught to him when he studied as a naval aviator. He showed me a three-ring binder, dating from about 1944, that contained star charts provided by the Navy. I remember seeing several charts on which Vega-Deneb-Altair were connected by lines and marked 'Summer Triangle.'"

Sir patrick's triangle?

Many wrote in to say that the legendary British astronomer, Sir Patrick Moore, was the first to coin the term. Sandy Wolford of Spencer, Indiana, found this comment by Moore in his 1992 book "Fireside Astronomy" (John Wiley and Sons).

"Many years ago, during a television broadcast, I introduced the nickname of "the Summer Triangle" and everyone now seems to use the term, even though it is completely unofficial and the three stars of the Triangle are not even in the same constellations."

While there is no reference in his book, to an exact date when he made this statement, it couldn't have been any earlier than April 1957. That's when Moore's monthly television program "The Sky at Night" made its debut on BBC television -- but three years after Rey first referred to the Summer Triangle.

Susan Rose, President of New York's Amateur Observers' Society (AOS), is a good friend of Moore.

"Patrick had not read Rey's books prior to using the phrase during one of his programs in 1958. When he used it, it caught on. It would seem that they coined it independently of each other but because of his TV presence, it became more widely known and therefore associated with him."

Finally, several others, like Jim Husnay of Minoa NY, pointed out that Romanian astronomer Oswald Thomas (1882-1963) described Vega, Altair and Deneb as "Grosses Dreieck" (Great Triangle) in the late 1920s and "Sommerliches Dreieck" (Summerly Triangle) in 1934.

Yet another triangle

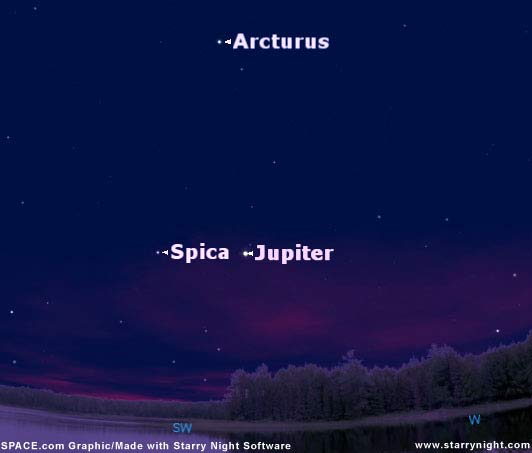

Interestingly, in our current evening sky, there is a somewhat smaller and brighter triangle configuration, although it is only temporary since one of the three points on the triangle is marked not by a star, but a planet.

Facing southwest this week at around 10-p.m. local daylight time, we can see an almost perfect isosceles triangle formed by the bright stars Arcturus and Spica and the brilliant planet Jupiter. This Triangle appears to point almost straight up, with the brilliant yellow-orange star Arcturus (magnitude --0.1) at the vertex. The bluish star Spica (magnitude +1.0) and the planet Jupiter (magnitude --2.0) form the bottom of the Triangle.

Unfortunately, this Triangle will be in a constant state of flux in the coming days and weeks because Jupiter will be slowly shifting to the east against the background stars. Finally, during mid-to-late September, first Spica and then Jupiter will become too deeply immersed in the sunset glow to be seen.

When they reappear in the morning sky during early November, Jupiter will have moved to the east of Spica. Teamed up again with Arcturus, Jupiter and Spica will still make for a very convincing Triangle. In fact, by the start of December, the Triangle's shape will pretty much replicate what we're seeing right now in our evening sky. The only difference is that Jupiter and Spica will have switched places.

Basic Sky Guides

- Full Moon Fever

- Astrophotography 101

- Sky Calendar & Moon Phases

- 10 Steps to Rewarding Stargazing

- Understanding the Ecliptic and the Zodiac

- False Dawn: All about the Zodiacal Light

- Reading Weather in the Sun, Moon and Stars

- How and Why the Night Sky Changes with the Seasons

- Night Sky Main Page: More Skywatching News & Features

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for The New York Times and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, New York.

| DEFINITIONS |

Degrees measure apparent sizes of objects or distances in the sky, as seen from our vantage point. The Moon is one-half degree in width. The width of your fist held at arm's length is about 10 degrees. 1 AU, or astronomical unit, is the distance from the Sun to Earth, or about 93 million miles. Magnitude is the standard by which astronomers measure the apparent brightness of objects that appear in the sky. The lower the number, the brighter the object. The brightest stars in the sky are categorized as zero or first magnitude. Negative magnitudes are reserved for the most brilliant objects: the brightest star is Sirius (-1.4); the full Moon is -12.7; the Sun is -26.7. The faintest stars visible under dark skies are around +6. |

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.