September's Harvest Full Moon Coming Next Week

This story was updated at 9:58 p.m. ET.

Over the next few nights, the earth's moon will be well placed for observation as it moves towards full moon on Sunday night (Sept. 12).

This month's full moon is special, because it is the Harvest Moon in the Northern Hemisphere. Because of the location of the sun, Earth, and moon this month, the nearly full moon will appear low in the southeastern sky for several nights in a row, which traditionally has allowed farmers an extension of daylight during the critical time of year when they are harvesting their crops.

The exact time of full moon will be 5:27 a.m. EDT (0927 GMT) on Sept. 12.

Phases of September's moon

Currently, the moon is in its waxing gibbous phase and not yet completely full. This sky map of the September's waxing gibbous moon shows how it will appear to skywatchers at mid-northern latitudes this week.

The first quarter and full moon, like the last quarter and new moon, are instantaneous events, marking the exact times when the geometry of the sun and moon, centered on the Earth, forms exact right angles. [Infographic: Phases of the Moon Explained]

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The seven-day spans between the four lunar phase markers are named for the shape the moon takes, crescent or gibbous, and whether the moon is growing (waxing) or shrinking (waning). Here's a rundown of the order of moon phases and the angles of the sun and moon, with respect to Earth:

- New moon: 0 degrees

- Waxing crescent

- First quarter: 90 degrees

- Waxing gibbous

- Full moon: 180 degrees

- Waning gibbous

- Last quarter: 270 degrees

- Waning crescent

- New moon: 360 degrees

Most people know what "crescent" means but are puzzled by "gibbous." It comes from an old Latin word gibbus meaning "hump," and refers to the hump shape that the moon assumes during this phase.

A lunar lover's delight

Some people may take the moon for granted, but it is worthy of a lot more attention from skygazers.

Take a careful look over the next few nights and you'll be surprised at how much detail you can see on the moon with your unaided eye. In fact, you can see more detail on the moon with your naked eye, than can be seen on Mars with the finest telescopes on Earth.

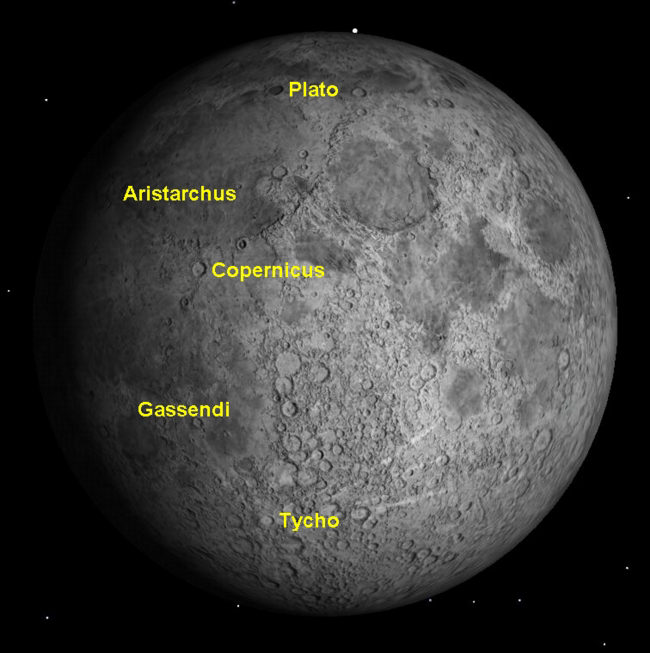

Use an ordinary binocular or small telescope and you’ll be able to see a number of the famous craters on the moon. These are named for the great astronomers of the past; only the craters named for the Apollo astronauts honor living people.

The most striking feature of the waxing gibbous moon is the bright band along its equator which divides it into two darker halves. This band is punctuated by the large crater Copernicus 58 miles (93 kilometers) in diameter. Examine this crater in a telescope to appreciate its complex terraced walls. [Photos: Our Changing Moon]

Look towards the northern edge of the moon for the dark-floored crater Plato, 63 miles (101 km) in diameter, and toward the southern edge for the brilliant Tycho 53 miles (85 km) in diameter. Plato is close to the arcing "shoreline" of the Sinus Iridum, the "Bay of Rainbows."

The ancient astronomers who named the plains of the moon "seas" and "bays" had no idea that it was an airless, waterless wilderness. Tycho is one of the youngest craters on the moon, a mere 100 million years old, and is the origin of a complex system of rays stretching half way around the moon.

With these as your guides, look more closely for the gigantic walled plain of Gassendi 68 miles (110 km) in diameter on the northern "shore" of the Mare Humorum, perfectly lit by the rising sun on Thursday night (Sept. 8). Observers with telescopes can see the complex system of rilles which crisscross its floor. On the moon, a "rille" is a crack in the surface where overlying material has collapsed.

The sun will rise over the Aristarchus, which is small in diameter (about 25 miles or 40 km), but is the brightest area on the whole moon, on Friday night (Sept. 9). Associated with Aristarchus is a huge mountain massif broken up by a winding valley, the Vallis Schröteri. Aristarchus is another fairly "young" crater, only 450 million years old and, like Tycho, is the origin of a complex ray system.

It’s interesting to use Wikipedia to explore the lives of the astronomers who have had craters named after them. Some, like Nicolas Copernicus and Tycho Brahe, are well known; others, like Pierre Gassendi, less so.

Then, for the next few nights, simply kick back and enjoy the beauty of the harvest moon, rising evening after evening in the east, and filling the late summer evenings with golden light.

This story was updated to correct the timing of September's Harvest Full Moon, which occurs at 5:27 a.m. ET on Monday, Sept. 12.

This article was provided to SPACE.com by Starry Night Education, the leader in space science curriculum solutions. Follow Starry Night on Twitter @StarryNightEdu.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Geoff Gaherty was Space.com's Night Sky columnist and in partnership with Starry Night software and a dedicated amateur astronomer who sought to share the wonders of the night sky with the world. Based in Canada, Geoff studied mathematics and physics at McGill University and earned a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Toronto, all while pursuing a passion for the night sky and serving as an astronomy communicator. He credited a partial solar eclipse observed in 1946 (at age 5) and his 1957 sighting of the Comet Arend-Roland as a teenager for sparking his interest in amateur astronomy. In 2008, Geoff won the Chant Medal from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, an award given to a Canadian amateur astronomer in recognition of their lifetime achievements. Sadly, Geoff passed away July 7, 2016 due to complications from a kidney transplant, but his legacy continues at Starry Night.