Confirmed! Scientists Tally Over 600 Alien Planets

For anyone keeping track, the number of confirmed alien planets now stands at more than 600, bolstered by the announcement today (Sept. 12) of 50 newfound alien worlds by the European Southern Observatory (ESO).

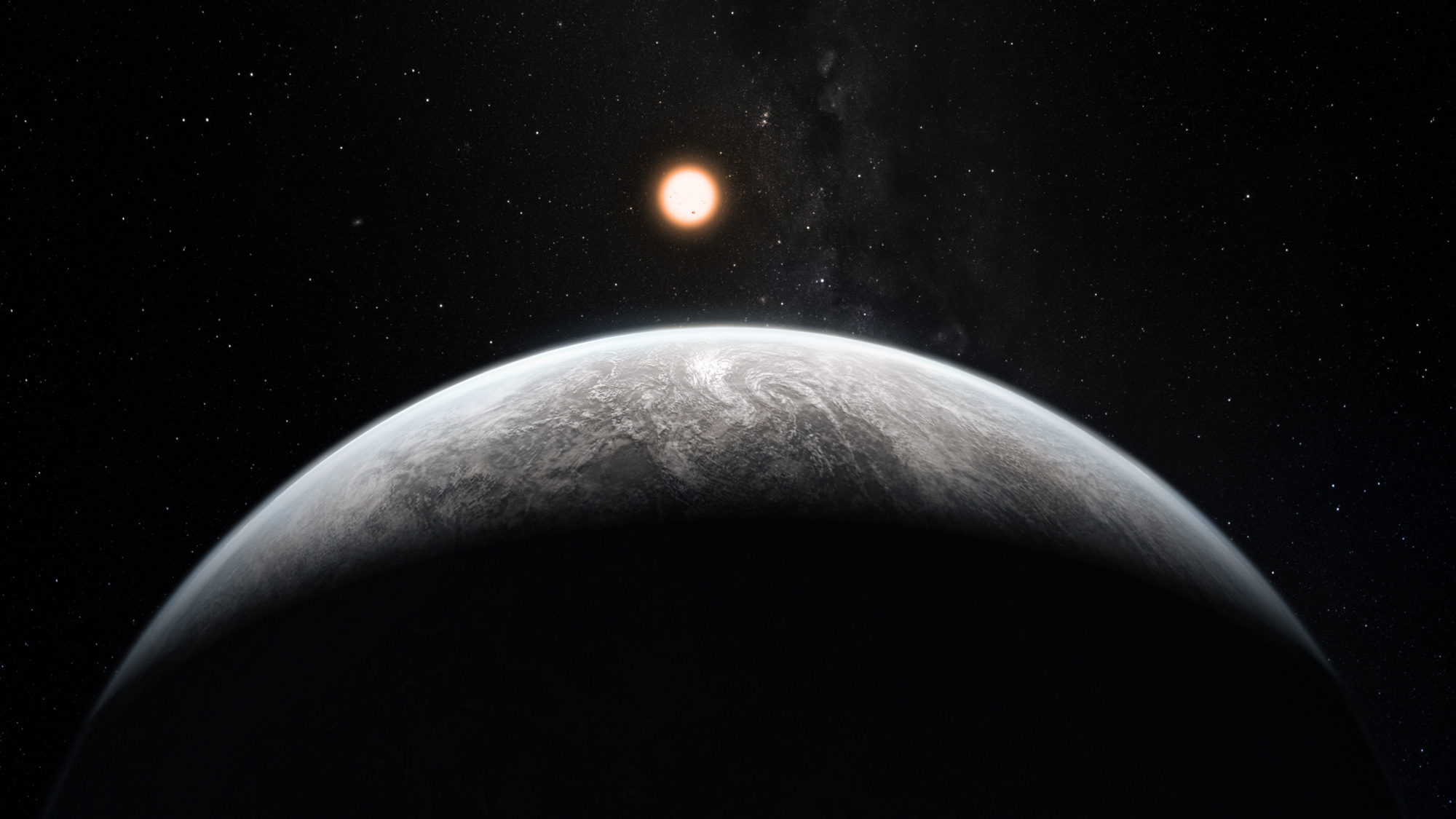

More than 50 new exoplanets — including one "super-Earth" that could potentially support life — were discovered using data from European observatory's High Accuracy Radial velocity Planet Searcher (HARPS) spectrograph, an instrument on the 11.8-foot (3.6-meter) telescope at the La Silla Observatory in Chile, ESO officials announced at the news briefing.

This bounty of alien planets is the latest in a string of discoveries that effectively pushed the current exoplanet tally past the 600 mark. Given the technological advances in the field of exoplanet research, it's possible we could see 1,000 confirmed alien worlds very soon, said Wesley Traub, chief scientist of NASA's Exoplanet Exploration Program at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif.

"The next big milestone should be 1,000," Traub told SPACE.com. "We are learning that there are so many planets out there, and many stars have multiple planets around then, that it's just a question of time until we get to that 1,000 mark of confirmed planets." [Gallery: The Strangest Alien Planets]

The search for alien worlds

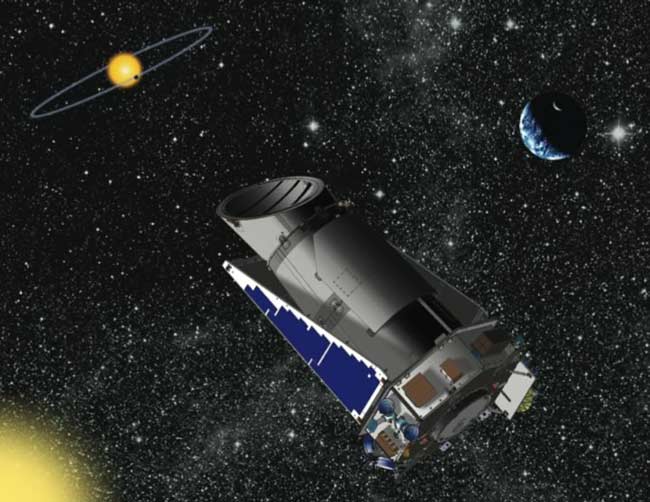

NASA's planet-hunting Kepler space observatory has identified more than 1,200 planetary candidates, which are potential worlds that require more observation before they can either be confirmed as exoplanets or deemed false positives.

Kepler uses the transit method to sniff out potential alien planets. This method looks for changes in a star's brightness caused by a planet crossing in front of it. ESO's HARP spectrograph, on the other hand, uses a technique called radial velocity that looks for repeated fluctuations in a star's movement potentially caused by a planet's gravitational pull.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"As technologies get better, we are able to discover things that are smaller and have smaller signals, whether it's radial velocities or transits," Traub said. "People have always been looking for these small planets, but we're pushing really hard to make radial velocity work better so we can find something like Earth. That's basically the holy grail of radial velocity. The same thing is true about transits."

The European Southern Observatory's new findings include 16 super-Earths, which are potentially rocky worlds that are more massive than our planet. Astronomers are especially interested in one, called HD 85512 b, which was found to orbit at the edge of its star's habitable zone, a region where conditions could be suitable to support life. [Infographic: Alien Planet HD 85512 b Holds Possibility of Life]

And while the current tally of exoplanets stands at just over 600, there are some discrepancies in how people classify these alien worlds.

According to the Extrasolar Planets Encyclopedia, a database compiled by astrobiologist Jean Schneider of the Paris-Meudon Observatory, there are now 645 detected alien planets.

Yet, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory's PlanetQuest website, which keeps a count of confirmed alien planets, lists 564 planets (not including the ESO exoplanets announced today).

Candidates vs. confirmed planets

This discrepancy is largely because the criteria for what constitutes an exoplanet can differ, based on the website or organization.

"If you look at the European site (Extrasolar Planets Encyclopedia), it includes anything that has been announced," Traub said. "It's trying to be as complete a list as possible, so it will always have the maximum number of planets of the sites that list them. If something is announced, [Schneider] adds it on there. He's very, very attentive that way."

NASA's PlanetQuest site, however, takes a much more conservative approach. PlanetQuest tends to not add an exoplanet to the list until it has been validated, checked, and the study has been accepted for publication, Traub said.

"It's a very stringent set of requirements," Traub said. "The rule is, we don't want to have any mistakes, so we don't necessarily care if we're six months behind. We want to be sure of the number we're writing down."

As for the amount of exoplanet findings that have been announced within the past two years, Traub explained that it's likely due to the serendipitous timing of the Kepler data's release, and other exoplanet-hunting missions.

"It's largely because of the accidental confluence of when Kepler was launched and when we're getting the data," Traub said. "Same with radial velocity. People are getting better and better at it with time. It's kind of an accident, but it's a wonderful accident."

You can follow SPACE.com staff writer Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Denise Chow is a former Space.com staff writer who then worked as assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. She spent two years with Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions, before joining the Live Science team in 2013. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University. At NBC News, Denise covers general science and climate change.