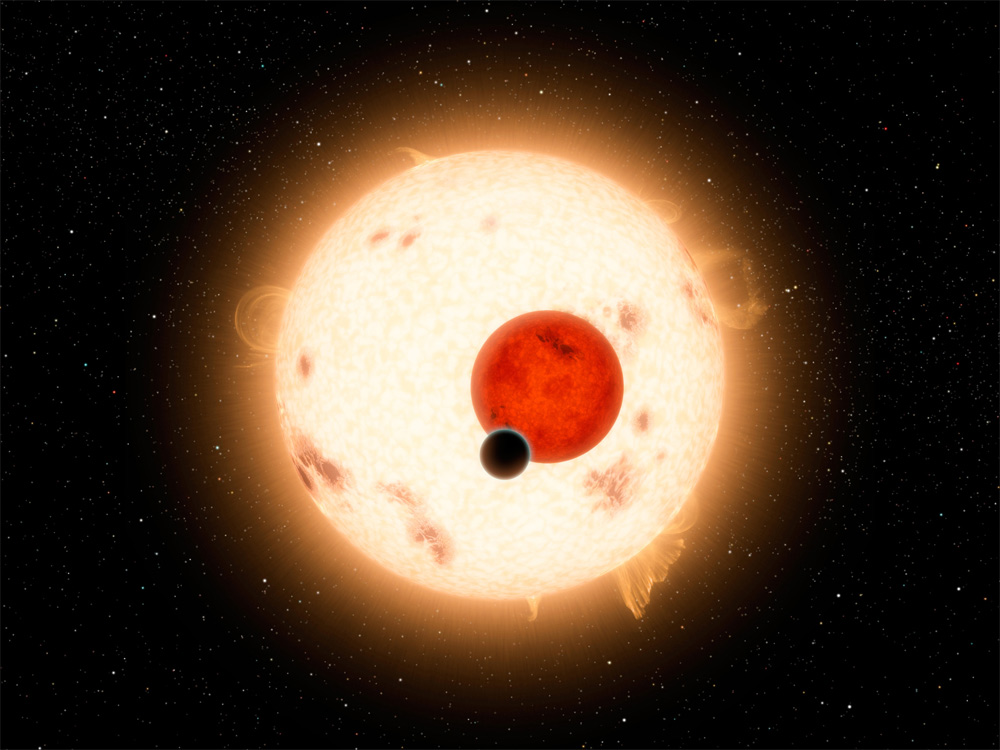

The first alien planet with two suns in its sky has just been found, but many more of them are almost certainly out there, scientists say.

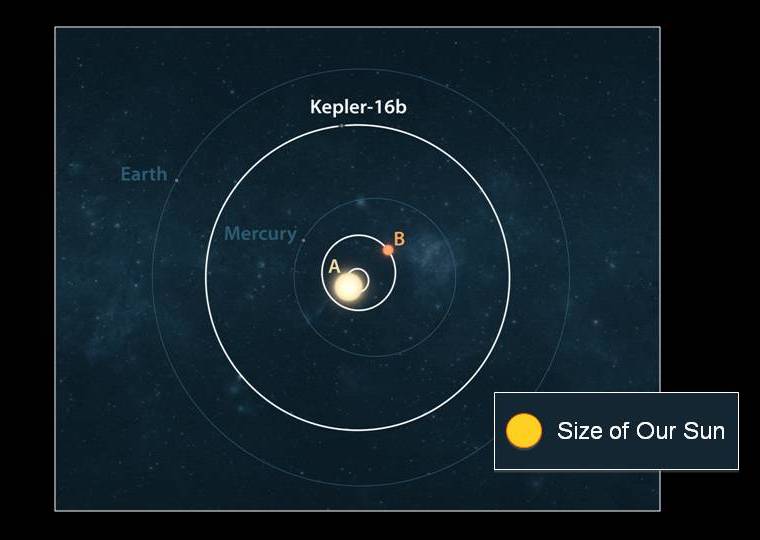

At a press conference yesterday (Sept. 15), researchers using NASA's Kepler space telescope announced the discovery of the planet, which is known as Kepler-16b. Like Tatooine — the home world of Luke Skywalker in the "Star Wars" films — Kepler-16b orbits a pair of stars rather than a singleton like our own sun.

Though Kepler-16b is the first such "circumbinary" planet to be unambiguously detected, it won't be the last, researchers said. [Photos: Real-life 'Tatooine' Planet With 2 Suns]

"We know now that, with very good likelihood, systems like this are common throughout the galaxy and indeed throughout the universe," said astronomer Greg Laughlin of the University of California, Santa Cruz, who was not involved in Kepler-16b's discovery.

Theory meets reality

Astronomers had long suspected that binary star systems could sport planets. After all, they've seen dusty debris disks — the raw materials from which planets are made — cloaking young double stars. [Infographic: New Planet is Like 'Star Wars'' Tatooine]

But binary systems are complex environments, Laughlin said, where gravity perturbations can toss alien planets out into space or send them barreling into one of their double suns.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

So Kepler-16b is an important find, showing that planets can both form and persist in binary systems. Computer simulations suggest that Kepler-16b's orbit will be stable for millions of years to come, said Laurance Doyle of the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) Institute, lead author of the study reporting the planet's discovery.

Circumbinary planets thus don't seem to be novelty acts. Rather, their numbers might rival those of the one-sun planets, which we've hitherto regarded as "normal."

"There are about as many binary stars as there are single stars," said Kepler project scientist Nick Gautier of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. "Planets around binary stars could be very common."

Life on a planet with two suns?

The Saturn-mass Kepler-16b is not a good candidate for life as we know it, researchers said. But there's no reason to think that life couldn't take root in a binary star system.

For starters, if a gas giant like Kepler-16b can coalesce and stick around in such a system, then a smaller, rocky planet — one more like Earth — almost certainly could as well, researchers said.

"Most theorists believe that in order to build up to a Saturn-size planet, you need to go through a kind of rocky, icy, terrestrial phase first," Laughlin said. "So the fact that you have this planet there, very clearly there, in my view implies it's much more likely that circumbinary terrestrial planets are going to exist."

If such planets happen to orbit in the so-called "habitable zone" of their double stars — the just-right range of distances that allows liquid water to exist — then life as we know it might be watching a double sunset somewhere right now.

Of course, a binary system's habitable zone would be a little more difficult to nail down concretely.

"We usually think of the habitable zone as a shell, a sphere around a single star," Doyle said. "Well, in this case, the habitable zone is moving as the two stars get closer and farther away from the planet. So the whole habitable zone is this big, very dynamic thing."

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.