Another Dead Satellite to Fall From Space in November

A defunct NASA satellite that fell to Earth last week sparked some worldwide buzz, but it's not the only spacecraft falling out of space.

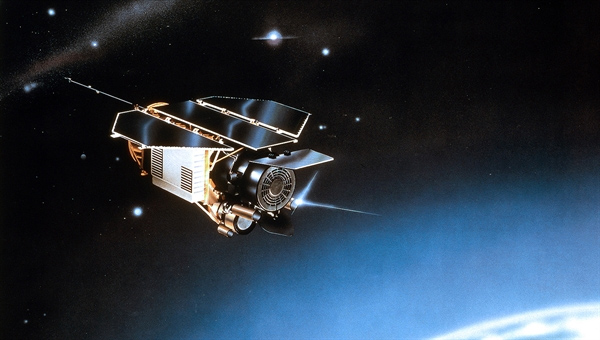

The decommissioned German X-ray space observatory, called the Roentgen Satellite or ROSAT, will tumble to Earth sometime in early November, but it's still too early to pinpoint exactly when and where debris from the satellite will land, according to officials at the German Aerospace Center.

The 2.4-ton spacecraft's orbit extends from the latitudes of 53 degrees north and south, which means the satellite could fall anywhere over a huge swath of the planet — stretching from Canada to South America, German Aerospace officials said. [6 Biggest Uncontrolled Spacecraft Falls From Space]

The latest estimates suggest that up to 30 large pieces of the satellite could survive the intense and scorching journey through Earth's atmosphere. In all, about 1.6 tons of the satellite components could reach the surface of the Earth, according to German Aerospace officials.

The re-entry will be similar to NASA's 6-ton Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite (UARS), which plunged into the southern Pacific Ocean on Saturday (Sept. 24).

ROSAT coming home

In 1998, ROSAT's star tracker failed, which caused its onboard camera to be pointed directly at the sun. The event permanently damaged the spacecraft and ROSAT was officially decommissioned in February 1999.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Scientists are actively tracking the dead satellite, but many of the details will remain uncertain until roughly two hours before it hits Earth.

"It is not possible to accurately predict ROSAT's re-entry," Heiner Klinkrad, head of the Space Debris Office at the European Space Agency, said in a webcast posted on the German Aerospace Center's website. "The uncertainty will decrease as the moment of re-entry approaches. It will not be possible to make any kind of reliable forecast about where the satellite will actually come down until about one or two hours before the fact."

It will, however, be possible to rule out certain geographical regions from the potential drop zone about a day in advance, Klinkrad said. The largest piece of debris is expected to be the telescope's heat resistant mirror.

"Generally speaking, whenever a satellite re-enters the atmosphere, about 20 to 40 percent of its mass actually reaches the Earth’s surface," Klinkrad said. "In the case of ROSAT, this figure could be slightly higher because one of its characteristic features is that it carries heat-resistant mirror structures on board." [Related: Falling Satellites & Space Junk: Q&A with Orbital Debris Expert]

Small risk to public

Fragments from ROSAT could fall back to Earth over a 50-mile (80-kilometer) wide path, but despite the uncontrolled nature of ROSAT's re-entry, the odds of personal injury or property damage are extremely remote, German Aerospace officials said.

When NASA's UARS satellite fell to Earth, for example, NASA said the chances of parts of the spacecraft striking any one of the nearly seven billion people on the planet were about 1 in 3,200. The actual personal risk of being hit for an individual person, however, was about 1 in several trillion, NASA officials said.

To date, there have been no reported serious injuries or casualties from falling space debris, NASA scientists have said.

You can follow SPACE.com staff writer Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Denise Chow is a former Space.com staff writer who then worked as assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. She spent two years with Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions, before joining the Live Science team in 2013. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University. At NBC News, Denise covers general science and climate change.