How to Spot Apollo Moon Landing Sites in Telescopes

If you have binoculars or a small telescope, now is a great time to observe the moon, and it might even be possible to pick out the landing sites of some of NASA's Apollo moon missions.

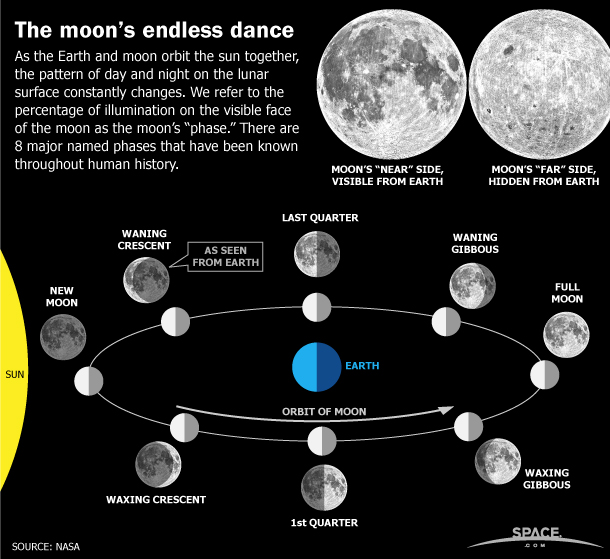

The days on either side of the moon's so-called first quarter are the best times to view our planet's natural satellite, and you don't even need fancy equipment for some stunning sights. The moon's first quarter this month occured Wednesday (Nov. 2) at 2:38 p.m. EDT.

At first quarter the moon is lit by the sun coming from the east. The sun is rising right along the terminator, which is the dividing line between sunlight and the dark of the lunar night.

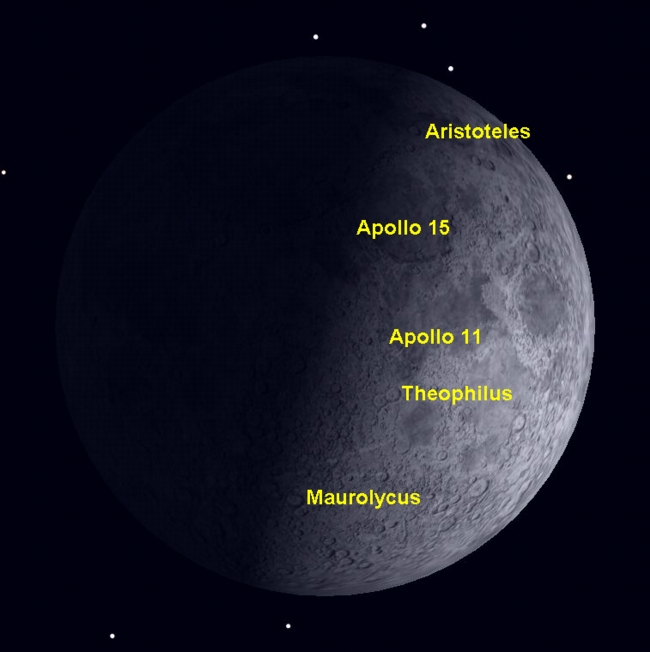

The map of moon's surface here lists likely targets for spotting famous moon craters or two Apollo lunar landing sites: Apollo 11 and Apollo 15.

Since the moon has no atmosphere, there is no twilight zone, no gradual transition between dark and light. The topography along the terminator is painted in stark contrasts of brilliant white and coal black. [Lunar Legacy: 45 Apollo Moon Mission Photos]

Spotting craters on the moon

It helps to get your bearings from some of the prominent craters visible on the moon's surface, the scars of impacts of asteroids that slammed into the moon billions of years ago.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Aristoteles is a large crater located near the moon’s north pole. Named for the Greek philosopher and scientist who lived in the fourth century BCE, it stretches 54 miles (87 km) across. Aristoteles is a complex crater with terraced walls.

Theophilus is a spectacular crater near the center of the moon’s disk. Theophilus was the bishop of Alexandria and died in 412 AD. This crater is 62 miles (100 km) wide. The crater's walls rise 3,940 feet (1200 m) above the surrounding terrain and its floor, complete with a large central peak, lies 14,400 feet (4400 m) below its rim.

Maurolycus is an even larger crater, 71 miles (114 km) across and 15,500 feet (4730 m) deep. It is named after Francesco Maurolico, an obscure 16th century opponent of Copernicus and his heliocentric theory that the Earth revolves around a stationary sun at the center of the solar system.

A striking feature of Maurolycus is that it appears to have hit and almost completely overlapped a slightly older crater. Theophilus and Maurolycus both have prominent central peaks, but Aristoteles has only a couple of small isolated peaks on its floor.

Using these craters as landmarks, it becomes possible to pinpoint and examine a couple of the Apollo landing sites.

Footsteps on the moon

The first Apollo landing on July 20, 1969 took place in the open flats of the Mare Tranquillitatis, just north of Theophilus. This location was chosen precisely because it was so flat, as the planners of the lunar mission wanted the first landing to be as easy as possible.

Even so, Neil Armstrong realized that they were headed for a rough area and took over manual control of the lunar lander to put it down on a smoother area, almost running out of fuel in the process.

Today there are three small craters just north of the Apollo 11 landing site named for the three first Apollo astronauts. Armstrong, at 2.9 miles (4.6 km) is the largest of the three. Aldrin is 2.1 miles (3.4 km) in diameter, and Collins is only 1.5 miles (2.4 km) large.

These small craters are a challenge to spot using small amateur telescopes but represent a great rarity: lunar craters named after living people. In most cases, you need to be dead to have a crater named after you.

Two years later, on July 30 1971, Apollo 15 touched down in a much more mountainous area to the northwest of the Apollo 11 landing site. The Apollo 15 site was located in a small valley just west of Mount Hadley, where a rugged mountain range, called the Lunar Apennines, forms a wedge between the Mare Serenitatis and the Mare Imbrium.

A long, narrow groove meanders across this valley, the Rima Hadley, and the astronauts explored this feature on the ground. If you have a fairly large telescope, at least 8 inches aperture, and lighting conditions are just right, you can get a "bird's eye" view of this surface feature yourself.

If you explore the Apollo landing sites with a small telescope, you won’t be able to see any of the objects left behind by the astronauts, as they are all too small to be resolved by even the largest telescopes.

In fact, it's only in the last two years that we’ve been able to photograph the landing sites in detail from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter.

This article was provided to SPACE.com by Starry Night Education, the leader in space science curriculum solutions. Follow Starry Night on Twitter @StarryNightEdu.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Geoff Gaherty was Space.com's Night Sky columnist and in partnership with Starry Night software and a dedicated amateur astronomer who sought to share the wonders of the night sky with the world. Based in Canada, Geoff studied mathematics and physics at McGill University and earned a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Toronto, all while pursuing a passion for the night sky and serving as an astronomy communicator. He credited a partial solar eclipse observed in 1946 (at age 5) and his 1957 sighting of the Comet Arend-Roland as a teenager for sparking his interest in amateur astronomy. In 2008, Geoff won the Chant Medal from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, an award given to a Canadian amateur astronomer in recognition of their lifetime achievements. Sadly, Geoff passed away July 7, 2016 due to complications from a kidney transplant, but his legacy continues at Starry Night.