Hubble Telescope Catches Never-Before-Seen Look at Black Hole's Maw

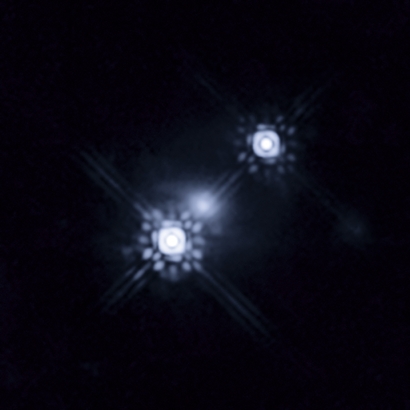

The Hubble Space Telescope has directly observed a disk of matter being sucked into a huge black hole.

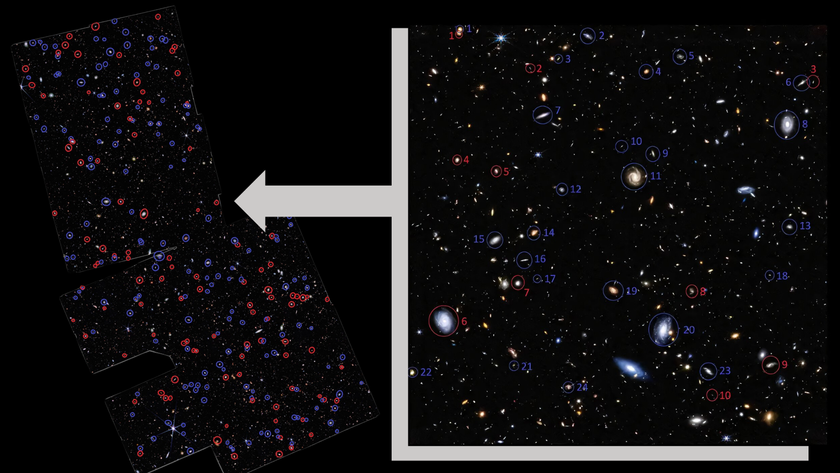

Astronomers capitalized on an effect called gravitational lensing to magnify the image, taking advantage of the warping of light by strong gravity that made the scene visible to Hubble. The high precision of the technique allowed the researchers to measure the size and temperature of the disk.

Such disks of matter falling onto extremely large supermassive black holes are called quasars, and are some of the brightest objects in the universe. As their mass is pulled into the black hole, the disks heat up and powerful radiation is released that makes them glow incredibly bright.

However, most of these are so far away from us on Earth that astronomers have a very hard time directly observing their structure.

"A quasar accretion disk has a typical size of a few light-days, or around 100 billion kilometers [62 billion miles] across, but they lie billions of light-years away," lead scientist Jose Muñoz of the University of Valencia in Spain said in a statement. "This means their apparent size when viewed from Earth is so small that we will probably never have a telescope powerful enough to see their structure directly." [Video: How Hubble Spotted the Quasar-Gobbling Black Hole]

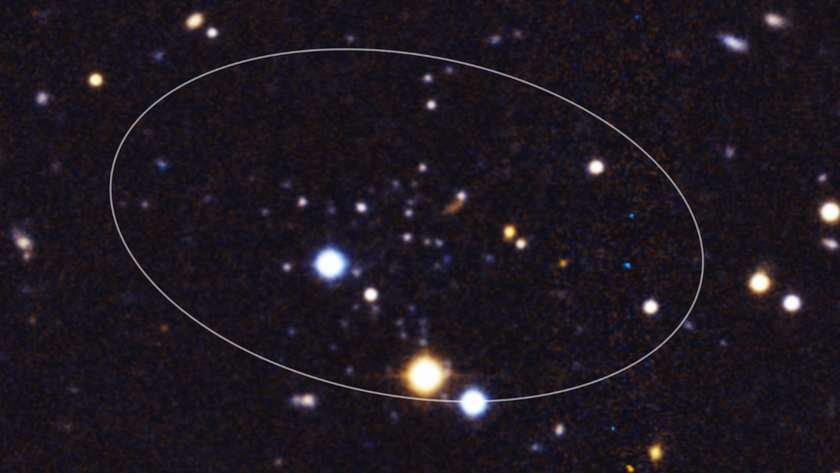

Luckily, this quasar happened to be directly behind a foreground galaxy, from our line of sight, whose stars' gravity acted like a lens to magnify the light coming from the quasar. This allowed the astronomers to glimpse details of the quasars that would otherwise be much too small to see.

The researchers observed small changes in color across the length of the quasar disk that correspond to different temperatures, proving new levels of detail about one of nature's most bizarre and powerful phenomena.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"This result is very relevant because it implies we are now able to obtain observational data on the structure of these systems, rather than relying on theory alone," Muñoz said. "Quasars' physical properties are not yet well understood. This new ability to obtain observational measurements is therefore opening a new window to help understand the nature of these objects."

The astronomers also calculated that the quasar is between four and eleven light-days across (approximately 62 billion to 190 billion miles, or 100 billion to 300 billion kilometers). A light day is the distance light travels in a day.

The findings are reported in the December 1 issue of the Astrophysical Journal.

Visit SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Space.com is the premier source of space exploration, innovation and astronomy news, chronicling (and celebrating) humanity's ongoing expansion across the final frontier. Originally founded in 1999, Space.com is, and always has been, the passion of writers and editors who are space fans and also trained journalists. Our current news team consists of Editor-in-Chief Tariq Malik; Editor Hanneke Weitering, Senior Space Writer Mike Wall; Senior Writer Meghan Bartels; Senior Writer Chelsea Gohd, Senior Writer Tereza Pultarova and Staff Writer Alexander Cox, focusing on e-commerce. Senior Producer Steve Spaleta oversees our space videos, with Diana Whitcroft as our Social Media Editor.