Could NASA's New Mars Rover Actually Find Martian Life?

NASA is launching a new robotic probe, called the Mars Science Laboratory to see if the Red Planet was once, or is now, habitable. But could it go one step further and discover signs of life?

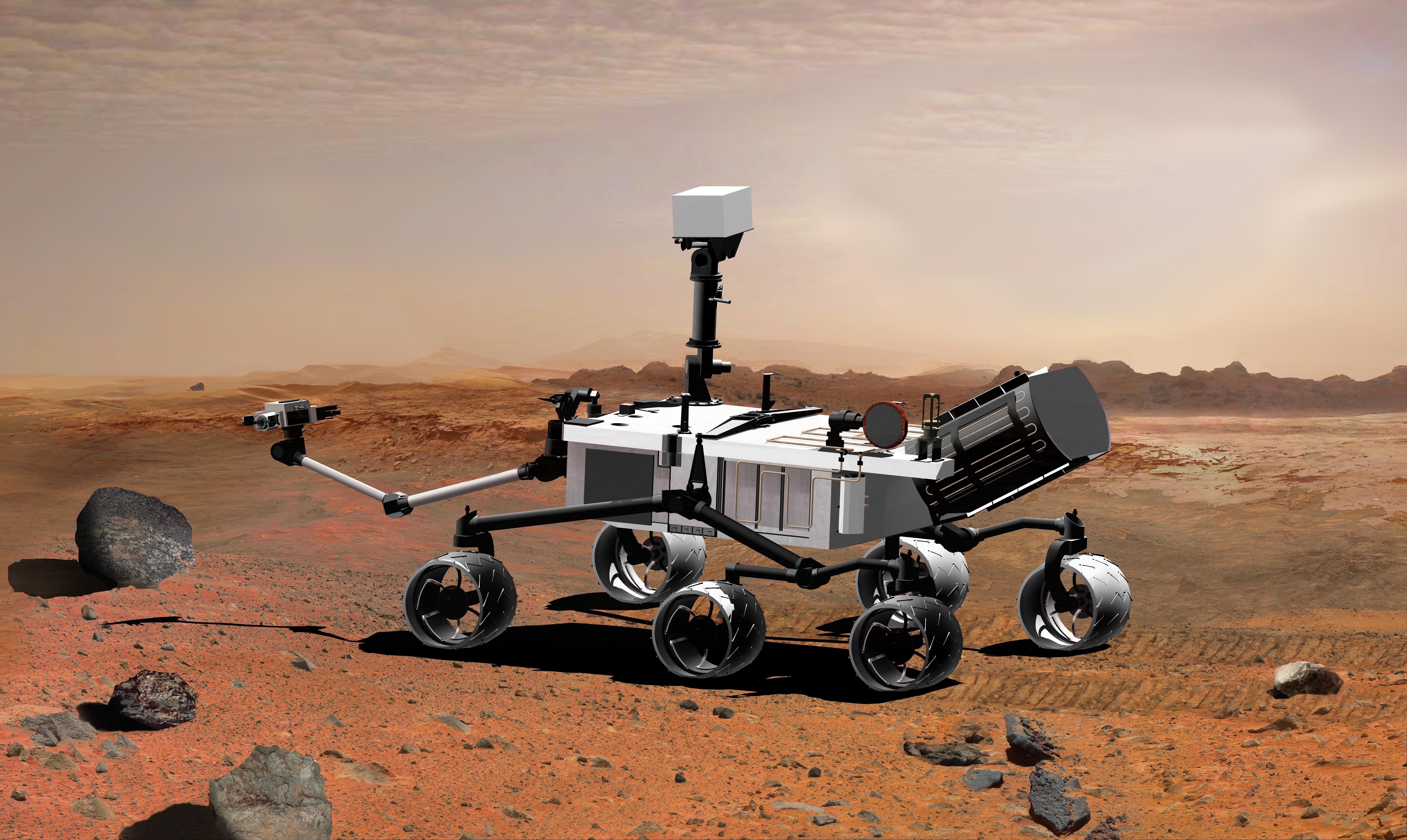

The mission will land a state-of-the-art rover named Curiosity near the equator of Mars. The car-size robot is loaded with tools that will help scientists probe the Martian surface more rigorously than ever before.

"We have this powerful mobile lab with many added capabilities that can help us ask more complex questions than ever, such as what makes a planet habitable, what might that evidence look like and whether we can see such evidence," astrobiologist and planetary scientist Pamela Conrad, deputy principal investigator for the Mars Science Laboratory, told SPACE.com.

For instance, Curiosity can drill into rock — a first for Martian rovers. It can then use microscopes, heat, X-rays and other scientific tools to see what the mineral, chemical and isotopic components are of samples it scoops up from the ground and inhales from the air.

"We also have a very powerful tool that is so science-fiction-y, so amazing," Conrad said. "ChemCam can fire a laser and make a little cloud of plasma when it hits the rock, and by scanning this plasma, it can scan what chemical elements are in the rock without even touching it."

In addition, Curiosity's wheels are relatively large, which will help it roll over obstacles that stopped past rovers in their tracks. Moreover, the plutonium fuel it carries will help power it at night when its solar panels do not work, which means it could potentially operate all day.

The fact that Curiosity is landing in a deep crater punched in the Martian surface will also help it analyze Mars' ancient history. A cosmic impact long ago essentially acted like a giant shovel that scientists can now use to investigate samples from untold layers of rock laid down over millions of years. This will enable scientists to effectively peer back into the planet's past. [7 Biggest Mysteries of Mars]

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"It's important to look at lots of samples from many different kinds of environments and moments in time as you can to better understand what a planet was like," Conrad said. "Since we can't go to all the different environments Mars has with just one rover, we can hopefully pick an environment that has accumulated diverse layers of sediment over time, so when we're looking at something as complicated as habitability, we have as much information at our fingertips as possible."

The problem with investigating the past or present habitability of Mars, "is that we've never found definitive evidence of life on Mars, so we don't know what makes one spot good or not for the kind of life that may or may not be there," Conrad said.

The goal of the Mars Science Laboratory then is to collect as much and as many different kinds of data about Mars as possible, and to compare what Curiosity learns with processes on Earth.

"We can try and deduce what the environment at our site is like now and what it was like in the past, and whether or not those were or are environments that life that we know of might be able to live in," Conrad said.

The question of asking whether life can or could have lived in an area, however, is very different than asking whether life did or does live there. Researchers have emphasized that Curiosity is not intended to find signs of life.

"We know what plants and animals look like on Earth, and we're very good at recognizing the molecular signatures of different microbes, but when we go to a different planet, we can have no certainty about what constitutes alien life," Conrad said. "What we can do is cross off all the things that we know aren't life and then look carefully at what's left. If we see organic molecules, can those be made by processes that aren't life or not?"

Even if Curiosity's microscope does spy a microbe scurrying across a sample, or if its scanners detect what might be biomolecules, such finds might not be conclusive evidence of life on Mars, "because we'd have to ask whether or not we brought them to Mars," Conrad said. "We have cleaned the spacecraft very carefully, but you'd have to ask whether anything we see that might be a sign of life was a contaminant, and we'd have a high burden of proof to overcome."

"We now have this wealth of information about all the extreme environments on Earth that organisms can live on that have expanded our notion of what might be possible," Conrad said. "We'll see what happens when the Mars Science Laboratory lands nine months after launch."

Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcomand on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us