How to See the Stars on the Longest Winter Nights

We are now only a few weeks away from the winter solstice Dec. 22. Anyone who lives in northern latitudes might have noticed how late the sun is rising and how early the sun is setting lately, especially since the end of Daylight Saving Time earlier this month.

Most people think of the winter solstice as the shortest day of the year, but stargazers tend to see it as the longest night of the year. On this date, the sun is above the horizon roughly 9 hours, varying with latitude. Subtracting twilight, the night is fully dark for almost 12 hours.

One result of this long night, combined with the southern position of the sun, is that a very large part of the night sky can be seen in one night. As evening twilight ends, the autumn constellations Cygnus, Pegasus and Aquarius fill the sky.

Then, as morning twilight begins, the spring constellations are visible: Hercules, Boötes, and Virgo. About the only constellations not visible at some point during the night are the ones very close to the sun, such as Ophiuchus, Sagittarius and Scorpius.

Long December nights

During the months between autumn equinox and winter solstice, the lengthening of the night almost keeps pace with the sun’s movement against the stars, so that the constellations visible at the end of evening twilight hardly seem to change. Pegasus hangs high in the southern sky for months on end. At the other end of the night, new constellations appear rapidly out of the dawn.

The opposite occurs once winter solstice is past: The morning sky changes hardly at all, while the autumn constellations rapidly disappear into evening twilight.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The long December nights allow us to take advantage of these celestial oddities. In particular, the late rising of the sun means that many people need to be up well before sunrise to get to work. If you can get up just a little bit earlier, you can get a jump on the spring constellations.

In particular, in the next few weeks until solstice, an early riser can observe two "morning stars," which are not really stars at all, but planets. These are not the usual suspects, Mercury and Venus, but rather two old friends only recently emerged from behind the sun: Mars and Saturn.

Morning stars

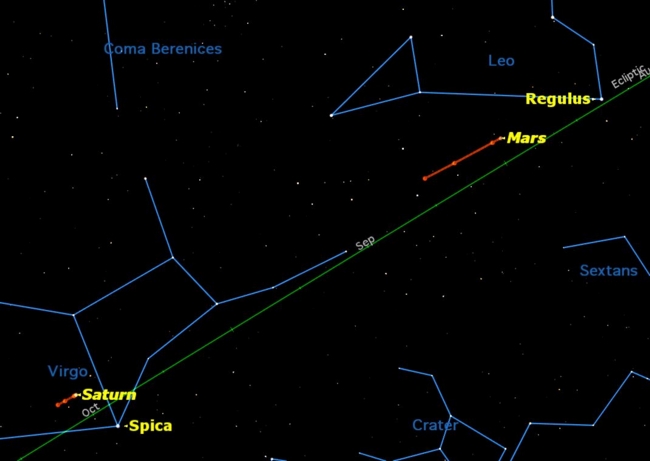

In the accompanying chart, the positions of the planets are shown for tonight, Nov. 30, and the orange trails show how they will move between now and Dec. 22. Mars’ trail is much longer because it is moving much faster due to its relative closeness to Earth.

By a happy coincidence, both planets are currently paired with bright stars, Regulus and Spica respectively. Both planets are also on the rise in brightness, but for different reasons.

Both planets are getting brighter because they’re getting closer. Mars is moving toward opposition, when it is angled 180 degrees from Earth, March 3, while Saturn is moving towards opposition April 15. At present both planets are just slightly brighter than the stars with which they are paired, but both will get much brighter by the time they reach opposition, especially Mars.

As a bonus, the moon will sail through both groupings on the mornings of Dec. 16 through Dec. 20, making for several fine viewing sessions and photo opportunities.

Editor's Note: if you capture a nice image and would like to share it with SPACE.com for a possible story or gallery, please email assistant managing editor Clara Moskowitz at cmoskowitz@space.com.

This article was provided to SPACE.com by Starry Night Education, the leader in space science curriculum solutions. Follow Starry Night on Twitter @StarryNightEdu.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Geoff Gaherty was Space.com's Night Sky columnist and in partnership with Starry Night software and a dedicated amateur astronomer who sought to share the wonders of the night sky with the world. Based in Canada, Geoff studied mathematics and physics at McGill University and earned a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Toronto, all while pursuing a passion for the night sky and serving as an astronomy communicator. He credited a partial solar eclipse observed in 1946 (at age 5) and his 1957 sighting of the Comet Arend-Roland as a teenager for sparking his interest in amateur astronomy. In 2008, Geoff won the Chant Medal from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, an award given to a Canadian amateur astronomer in recognition of their lifetime achievements. Sadly, Geoff passed away July 7, 2016 due to complications from a kidney transplant, but his legacy continues at Starry Night.