Monster Black Holes Are Most Massive Ever Discovered

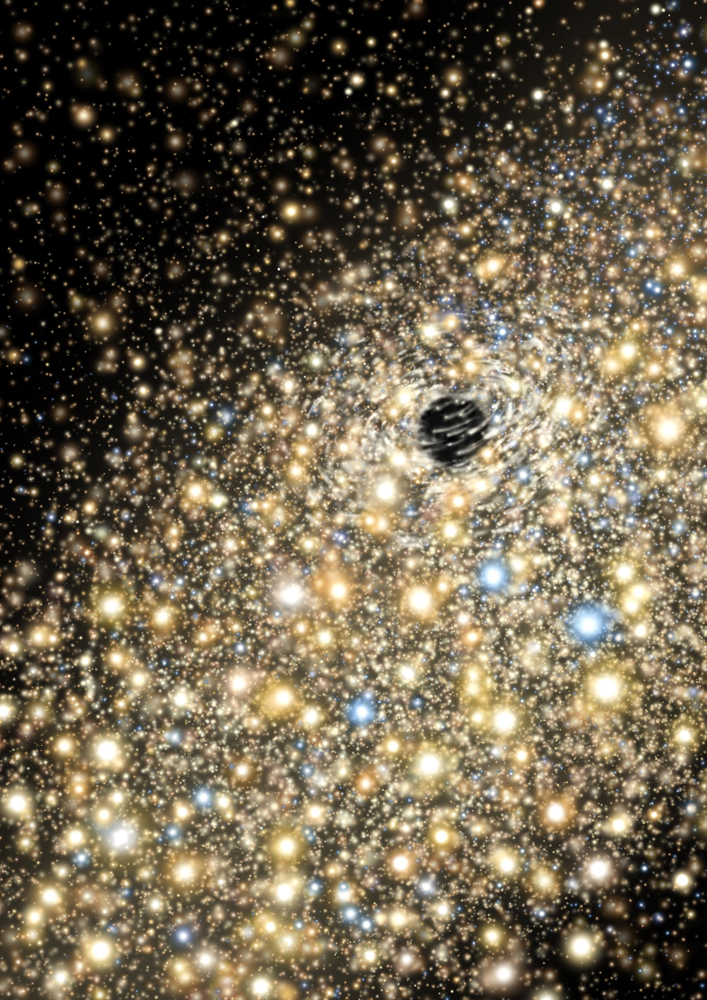

Scientists have discovered the largest black holes yet, and they're far bigger than researchers expected based on the galaxies in which they were found.

The discovery suggests we have much to learn about how monster black holes grow, scientists said.

All large galaxies are thought to harbor super-massive black holes at their hearts that contain millions to billions of times the mass of our sun. Until now, the largest black hole known was a mammoth dwelling in the giant elliptical galaxy Messier 87. This black hole has a mass 6.3 billion times that of the sun.

Now research suggests black holes in two nearby galaxies are even bigger. [Photos: Black Holes of the Universe]

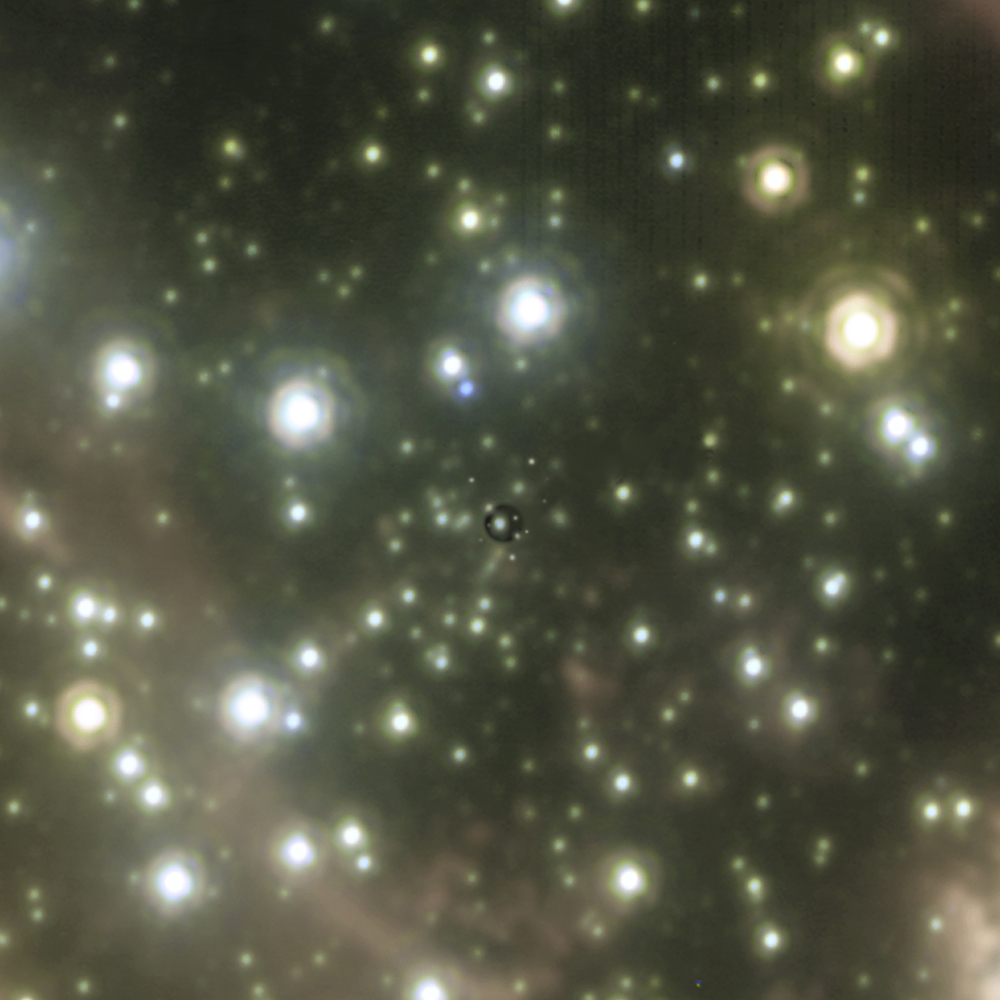

The scientists used the Gemini and Keck observatories in Hawaii and the McDonald Observatory in Texas to monitor the velocities of stars orbiting around the centers of a pair of galaxies. These velocities reveal the strength of the gravitational pull on those stars, which in turn is linked with the masses of the black holes lurking there.

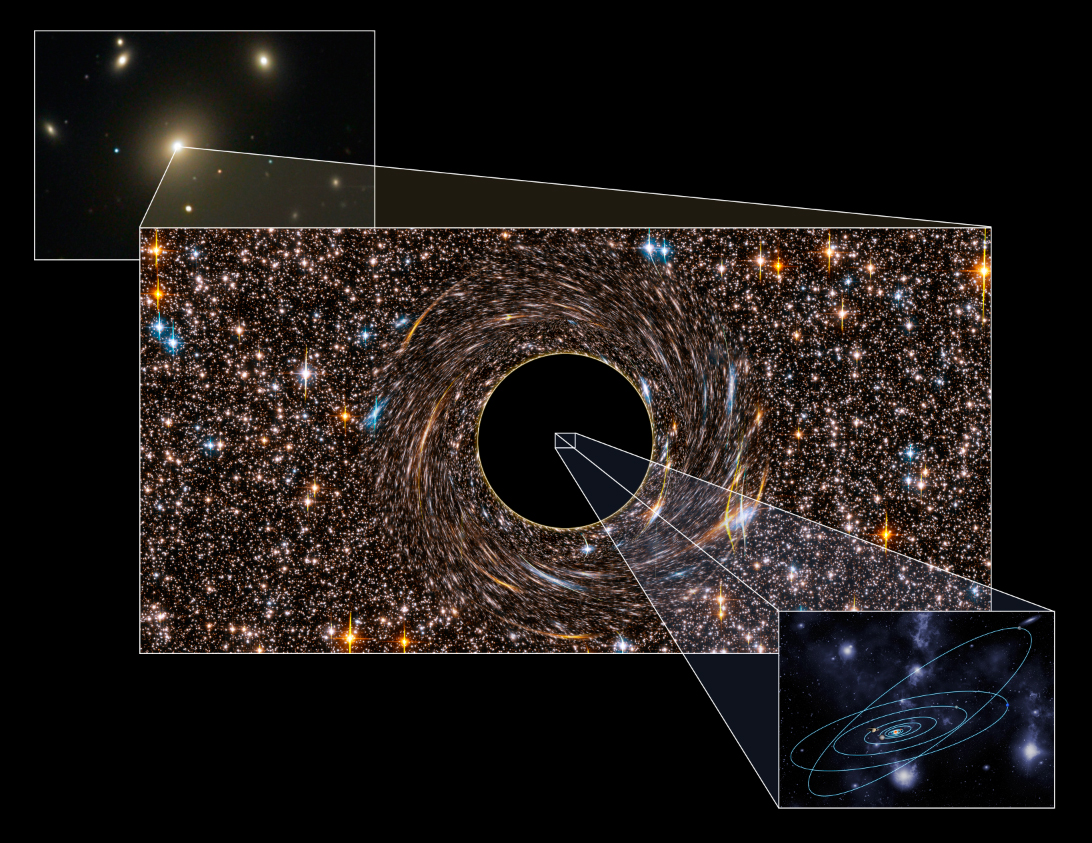

The new findings suggest that one galaxy, known as NGC 3842, the brightest galaxy in the Leo cluster of galaxies nearly 320 million light years distant, has a central black hole 9.7 billion solar masses large. The other, named NGC 4889, the brightest galaxy in the Coma cluster more than 335 million light years away, has a black hole of comparable or larger mass. Both encompass regions or "event horizons" about five times the distance from the sun to Pluto.

"For comparison, these black holes are 2,500 times as massive as the black hole at the center of the

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Milky Way galaxy, whose event horizon is one-fifth the orbit of Mercury," said study lead author Nicholas McConnell at the University of California, Berkeley.

Astronomers had suspected that black holes more than 10 billion solar masses large exist, based on light from quasars, cosmic objects from the early universe that are no more than a light year or two across but are thousands of times brighter than our entire galaxy.

The light of quasars is thought to come from matter driven to incandescent brightness as it spirals at high speeds into supermassive black holes. This is the first time scientists have detected black holes approaching such theorized giants in size.

"These two new supermassive black holes are similar in mass to young quasars, and may be the missing link between quasars and the supermassive black holes we see today," said study co-author Chung-Pei Ma, an astrophysicist at the University of California, Berkeley.

The researchers suggest these relatively dim black holes may be the aged remnants of quasars — "their central black holes are no longer fed by accreting gas, so have become dormant and hidden," Mai told SPACE.com. "The boisterous quasars may have passed through a turbulent youth to become quiescent giant elliptical galaxies."

This pair of black holes is 1.6 to 4.6 times more massive than one would predict from their galaxies, based on details such as the brightness of the bulges at their centers. These findings suggest that black holes may grow differently in large galaxies than in small ones.

"We know that bigger galaxies are made by mergers of smaller galaxies, and during this process, the black holes at the centers of the smaller galaxies can merge to form bigger black holes," Mai said. "But black holes can also grow by being fed by gas in their vicinity. It's a bit like asking, 'Are taller children produced by taller parents or by eating a lot of spinach?' For black holes, we are not sure."

The researchers are now analyzing data on even more black holes. They detailed their findings in the Dec. 8 issue of the journal Nature.

Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us