A newly discovered comet is racing toward a mid-December rendezvous with the sun — a rendezvous that it will likely not survive.

The comet is categorized by astronomers as a "sungrazer" and it is destined to do just that; literally graze the surface of the sun (called the photosphere) and pass through the sun's intensely hot corona, where temperatures have been measured at upwards of 3.6-million degrees Fahrenheit (2-million degrees Celsius).

While the comet will not collide with the sun, most astronomers say the odds are rather long that it will remain intact after its closest pass by the sun. The most exciting aspect of the event is that the comet's expected destruction should be visible on your computer monitor.

And there is a very slight chance that, should the comet somehow manage to survive, it might briefly become visible in broad daylight. [Amazing New Sun Photos from Space]

Discovery

The comet was discovered by Australian amateur astronomer Terry Lovejoy Nov. 27 using a C8 Schmidt-Cassegrain telescope, working with a QHY9 CCD camera.

At first, Lovejoy believed that the rapidly moving fuzzy image he saw was nothing more than a camera reflection. But two nights later, despite clouds and haze, he managed to find the fuzzy object again and take several new images.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Lovejoy then put out a call to some trusted observers to confirm his observations. He received that confirmation Dec. 1 from Mount John Observatory, based in the Mackenzie Basin on the South Island of New Zealand. By then, 31 separate observations of the comet had been collected to determine an orbit, and the first announcement of Lovejoy's discovery was made this past Friday (Dec. 2) by the Minor Planet Center of the International Astronomical Union.

Its official title is C/2011 W3 (Lovejoy). It is Terry Lovejoy's third comet discovery.

Grazing the sun

Astronomer Gareth V. Williams computed a preliminary orbit for the comet, which indicates that perihelion (closest approach to the sun) will occur at 7 p.m. EST Dec. 15 (00:00 GMT on Dec. 16) at a distance of 548,000 miles (882,000 km) from the center of the sun, meaning that the comet will skim a mere 115,000 miles (186,000 km) above the solar surface, putting it into the special classification of a "Kreutz Sungrazer."

"I'm still quite stunned by the fact that W3 is a Kreutz Sungrazing comet," Lovejoy said. "This

is a very special discovery to me as I have long been fascinated by the Kreutz Sungrazing comets; it has been over four years since my last discovery and I do hope the next one comes a lot sooner!"

Lovejoy's discovery is rather special since it marks the first time that a Kreutz Sungrazer has been discovered from a ground-based telescope in over 40 years. Usually, such comets are discovered only within a few days of their closest approach to the sun, from satellite imagery.

Kreutz

In the year 1888, astronomer Heinrich Kreutz (1854-1907) noted that sungrazing comets all followed along approximately the same orbit.

Astronomers now think they were once all bits of a single giant comet that fragmented in the distant past. And it's quite probable that these fragments have themselves broken up repeatedly as they've orbited the sun, resulting in different comets at periods ranging from about 500 to 800 years.

In honor of Kreutz's work, this special group of comets is named the Kreutz Sungrazers.

Two of these sungrazers (seen in 1843 and 1882) not only developed very long tails but also achieved the rare distinction of having been bright enough to be seen in broad daylight with the unaided eye.

And the brightest comet of the 20th century appeared in the autumn of 1965: Comet Ikeya-Seki. On Oct. 21, 1965, many could easily view this comet with the naked eye if the sun was hidden behind the side of a house or just an outstretched hand. In Japan the comet was described as appearing about 10 times brighter than the full moon.

Tiny grazers

Until 1978, only about a dozen sungrazing comets had been positively identified.

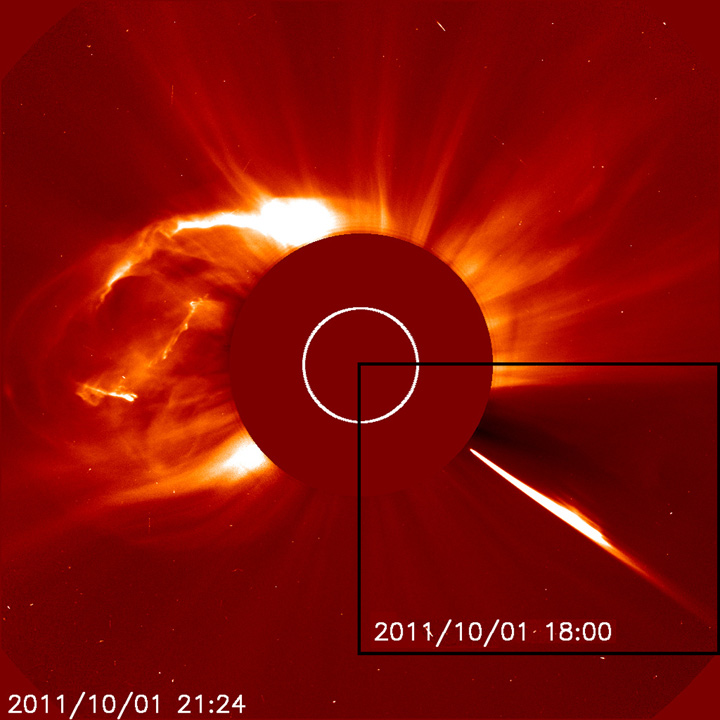

Beginning in 1979, orbiting space observatories began to detect sungrazing comets using instruments called coronagraphs. A coronagraph is designed to look at the solar atmosphere by blocking out the bright disk of the sun. Tiny sungrazing comets, which normally would be too faint and too near to the glare of the sun, can be picked up using a coronagraph.

In fact, sungrazers are now routinely being discovered using the Large Angle Spectrometric Coronagraph on the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) satellite. In fact, SOHO is the most successful comet discoverer in history, having found 2,110 comets over 16 years of operation — an average of one about every three days.

What's even more impressive is that the majority of these comets have been found by amateur astronomers and enthusiasts from all over the world, scouring the SOHO images for likely comet candidates from the comfort of their own homes.

Absolutely anyone can join this project — all you need is an Internet connection and some free time. If you want to join the hunt, go to: http://sungrazer.nrl.navy.mil/index.php?p=cometform.

Some of these are probably just a few meters across; none have survived their sweep around the sun.

The fate of Comet Lovejoy

In a way, Kreutz comets are like trains of all sizes moving along the same railroad track while passing our station (Earth) in space. And like impatient commuters, we can only watch and wonder what awaits us up the track. As we noted earlier, literally thousands of sungrazers have flicked past the sun as tiny objects briefly visible via satellite imagery.

Some Kreutz comets are very bright and spectacular.

Given that at least 10 have reached naked-eye visibility over the last 200 years, another could be just around the corner. The last Kreutz Sungrazer to become bright was Comet White-Ortiz-Bolelli in May 1970. Before that was the dazzling Comet Ikeya-Seki in 1965.

Since Comet Lovejoy is the first sungrazer in over-40 years to be discovered en route to the sun with an Earth-based telescope, one might wonder if it will evolve into a memorable spectacle.

Unfortunately, while Lovejoy is probably many times larger than the vast majority of the Kreutz Sungrazers that sweep to their ultimate solar demise, it is likely many times smaller than the spectacular Kreutz comets of the past. In fact, when at the same distance from the sun that Comet Lovejoy is now, Comet Ikeya-Seki appeared over-1,000-times brighter.

Ikeya-Seki and the nine other naked-eye sungrazers that have appeared over the last two centuries managed to survive their close shaves with the sun because they were physically large as well as moving with tremendous speed. Indeed, at perihelion, sungrazing comets literally describe a hairpin turn around the sun at over-a-million miles per hour.

But even those larger Kreutz specimens sometimes emerge from their solar meetings in shambles. The nucleus of Ikeya-Seki fractured into at least three pieces; the Great Comet of 1882 may have broken into six or eight pieces.

According to John Bortle of Stormville, N.Y., who has observed several hundred comets in his more-than-50 years as an assiduous amateur astronomer, Comet Lovejoy, "appears to be only modestly condensed, at best, and lacking in any obvious stellar nucleus, even a very faint one. In my mind this does not bode particularly well for this diminutive object. If it already may be seriously depleted in its meager reserves of volatiles, how much will be left available for its final death plunge into the solar corona?"

Bortle adds that another comet (du Toit in 1945) reportedly exhibited a similar physical appearance to Comet Lovejoy en route to the sun and was of a similar brightness.

Ultimately, du Toit totally faded away before ever reaching the sun. Is this Comet Lovejoy's future? "I hope not, but I really have to wonder," Bortle said.

Death of a comet . . . on your computer!

To get a good view of Comet Lovejoy, reserve a seat next to your computer and stay tuned to the SOHO website: http://sohowww.nascom.nasa.gov/data/realtime/c3/512/.

Comet Lovejoy (if it hasn't faded completely away) is expected to enter camera range beginning next Monday (Dec. 12), appearing to move rapidly up from the south, then rapidly curve up and around the sun in what may prove to be a fiery demise Dec. 16.

There is also the ever-so-slight chance that this comet might briefly become visible in broad daylight around that time as well.

But that's only assuming the comet somehow survives its close brush with the sun, which doesn't look very likely. Then again, you never know.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for The New York Timesand other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, New York.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.