Human spaceflight turned 50 this year, but 2011 was less about drawing inspiration from the past than about transitioning to an uncertain future.

The year marking the 50th anniversary of Yuri Gagarin's historic first spaceflight also saw NASA ground its storied space shuttle fleet after three decades of service. The United States now has no vehicle capable of lofting astronauts to Earth orbit or beyond, although NASA and several private aerospace companies are working to change that.

2011 also saw NASA announce designs for a new spaceship and a heavy-lift rocket that will someday propel people toward deep-space destinations such as an asteroid or Mars.

"The year truly marks the beginning of a new era in the human exploration of our solar system," NASA administrator Charlie Bolden said on Dec. 20. [Vote: Biggest Spaceflight Stories of 2011]

It was also a year when China set an aggressive course toward establishing its own permanent manned presence in space.

No more space shuttle

The space shuttle era came to a close when Atlantis touched down at Florida's Kennedy Space Center on July 21, wrapping up its STS-135 mission.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

NASA is now completely dependent on Russian Soyuz vehicles to ferry its astronauts to and from the International Space Station, paying $63 million per seat. This state of affairs troubles many observers, and the crash of Russia's Progress 44 supply vessel highlighted their concerns.

The unmanned Progress 44 launched on a cargo run to the space station Aug. 24 but didn't make it very far. It crashed in Siberia five minutes after liftoff, doomed by a problem with the third stage of its Soyuz rocket. Russia uses a similar version of the Soyuz to launch astronauts, so manned flights were suspended until the problem could be identified and fixed.

NASA has always intended its reliance on Russia to be temporary. The agency wants private American spacecraft — operated by commercial companies such as SpaceX, Blue Origin, Sierra Nevada and Boeing — to take over the Soyuz's orbital taxi role as soon as safely possible. [Top Private Spaceships Headed for Reality]

Just when that will happen is up in the air, however. NASA had pegged 2016 as a proposed start date, but recent cuts by Congress to the agency's Commercial Crew Development program are likely to push things back until 2017 at the earliest, officials said recently.

A new spaceship and rocket

In 2010, President Barack Obama instructed NASA to work toward getting astronauts to an asteroid by 2025 and to Mars by the mid-2030s. The shuttle program's end frees up some resources for such ambitious projects, and this year the agency laid out how it plans to reach these deep-space destinations.

In May, NASA announced that astronauts will ride in a spaceship called the Orion Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle, which is based heavily on the Orion capsule concept from the agency's defunct moon-oriented Constellation program.

And in September, NASA unveiled the giant rocket that will blast Orion off the pad. The $10 billion Space Launch System (SLS) will loft 70 tons of payload in its early incarnations, and the space agency hopes to beef up the booster to handle 130 tons eventually. The plan is for the Orion-SLS combo to be operational by 2021.

Selecting a heavy-lift rocket design this year was a big deal, some analysts say, giving NASA and its human spaceflight program stability and direction.

"The decision to go ahead and develop the SLS is the thing that I think will have lasting impact" from this year, said space policy expert John Logsdon, professor emeritus at George Washington University.

Future not assured

The Obama administration has committed to the SLS, and the program has some powerful supporters in the Senate — notably Kay Bailey Hutchison, R-Texas, and Bill Nelson, D-Fla. But long-term support for the heavy lifter is not guaranteed, Logsdon said.

The SLS also has its share of critics who regard it as too expensive. Further, Hutchison is retiring and Nelson faces a tough re-election fight in 2012. The president's re-election is also not assured, Logsdon noted.

So January 2013 could bring yet more transition to NASA.

"The question is whether there will be any champions of the current approach left in the Congress, and what a new president, if it's not Obama, would do," Logsdon told SPACE.com.

"Fragile" is a good word to describe the U.S. human spaceflight program at the end of 2011, Logsdon said. "It's on a path that is discernible, but there are all kinds of factors that could cause that path not to be followed."

China rising?

It was a year of transition for more than just NASA. China also made some big moves.

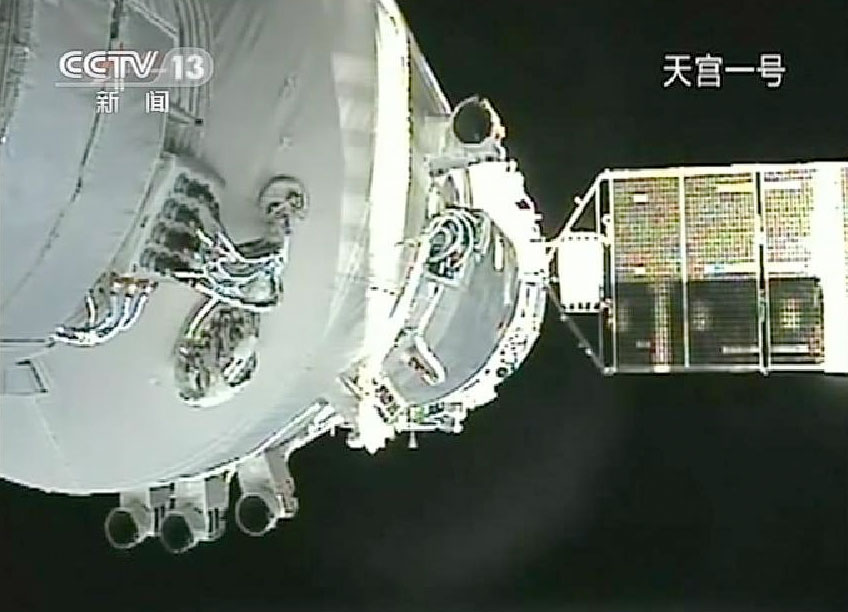

On Nov. 2, the nation successfully docked two unmanned spacecraft in orbit, a first for China. The mating of the Shenzhou 8 and Tiangong 1 vessels was designed to test technologies that China will use to build a space station in orbit. Beijing hopes to have a 66-ton manned station operational by 2020.

2012 is likely to see more progress toward this goal. China plans to launch two more docking missions, and officials have said that at least one of them will be manned.

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.