Soaring on Titan: Drone Airplane Could Scout Saturn's Moon

Physicist Jason Barnes was just six years old in 1982 when scientists first came up with the Cassini spacecraft mission that would tour Saturn's rings and moons more than two decades later. Now, a fully-grown Barnes has the even wilder idea of sending a robotic aircraft soaring through the skies of Saturn's mysterious moon Titan.

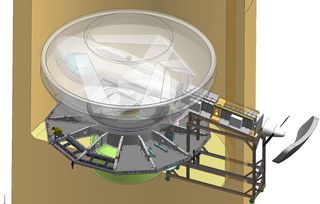

The "AVIATR" drone design looks eerily similar to those of U.S. military drones patrolling the skies above Earth's battlefields. But it could fly through Titan's skies far more easily than those of Earth — the Saturn moon has seven times less gravity and more than three times denser atmosphere to give wings extra lift. That would allow the drone to stay airborne almost forever on nuclear batteries with two-light bulbs-worth of power as it scouts the surface of Titan.

"Because it would be electrically powered by ASRGs (Advanced Stirling Radioisotope Generators), we could theoretically go forever on that power," said Barnes, a physicist at the University of Idaho. "The nominal mission is a year, but we don't really have an upper limit. We could maintain flight indefinitely."

A robotic airplane could fly on Titan more efficiently than a hot-air balloon, say Barnes and his colleagues. It could also swoop below Titan's atmospheric haze and take detailed images of the moon's surface that usually lies hidden from the cameras of Cassini or other spacecraft in orbit.

We have the technology

Flying an aircraft on a moon of Saturn where methane falls as rain may seem wildly futuristic, but the drone doesn't require much new technology. One of the AVIATR drone designers, Richard Foch of the Naval Research Laboratory, has already created tens of drones for the U.S. Navy.

"We're really taking advantage of the fact that the Defense Department has spent tens of billions of dollars to create the tech we need," Barnes told InnovationNewsDaily. "If you proposed it 10 years ago, it'd be crazy — you would need a lot of development just to create the autonomous software to do long-term navigation."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The drone would enter Titan's atmosphere in an aeroshell similar to one that protected the Huygens probe dropped by Cassini in 2005. Once a parachute had deployed to really slow down the descent, the aircraft would unfold its wings tucked beneath it, turn on the propeller and fly out of the aeroshell.

The power source is one of the few exceptions for new technologies. The ASRGs being developed by NASA resemble more-efficient versions of existing nuclear batteries that harness energy from the radioactive decay of material such as Plutonium 238.

Flying to save energy

That still only amounts to about 250 watts, or two-light bulbs-worth of power, for AVIATR. The power supply limits how much information the drone can beam back to Earth when using the satellite dish tucked into its oversized nose.

Rather than load up the drone with extra batteries, the mission designers came up with a clever solution. AVIATR could climb to 8.7 miles (14 kilometers) up in Titan's atmosphere, stop its propeller and then redirect all power to the upload beam as it glides down to just 2 miles (3.5 km) above the moon's surface.

The drone is expected to beam about 1 gigabyte of data about Titan's methane rainfall, winds, clouds and other weather information back to Earth within a year — the equivalent of about 200 songs in mp3 format. A side-view camera could reveal views of Titan's clouds stretching out across the horizon.

Picturing a moon of Saturn

AVIATR would also carry a high-resolution camera — similar to the HiRISE camera aboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter — capable of imaging objects as small as 10 inches (25 cm) per digital image pixel. That would allow it to take images at the peak of its climb to build a mosaic map of Titan's surface, even as it also captures high-resolution images at the bottom of its glide.

The drone could even fly along the shoreline of one of Titan's many lakes, or observe one of the moon's many extraterrestrial features that seem strangely similar to those on Earth.

"Titan is a wild and diverse place," Barnes said. "We want to get Huygens-quality imaging on tens of sites on Titan: lakes, sand dunes, mountains and channels."

Putting Titan on the menu

The AVIATR drone originally began as part of a bigger Titan mission involving a space orbiter and a robotic craft called the Titan Mare Explorer intended to splash down in one of Titan's largest seas. But its proposed $715 million budget has now left it stranded in the price range of NASA's New Frontiers class of missions.

New Frontiers missions must target scientific targets deemed high priority by the Planetary Science Decadal Survey — but Titan was not on the menu for the most recent round. Now Barnes has settled in for a career-long quest to build up support for Titan in the 2019 survey, so that a mission might launch in the late 2020s.

Still, the physicist takes heart from past researchers who didn't give up in the decades-long quest to launch the Cassini-Huygens mission.

"People laid the groundwork for me, so I'm going to try returning the favor by doing the groundwork for future missions," Barnes said.

The AVIATR is detailed in the Dec. 20, 2011, online edition of the journal Experimental Astronomy.

You can follow InnovationNewsDaily Senior Writer Jeremy Hsu on Twitter @ScienceHsu. Follow InnovationNewsDaily on Twitter @News_Innovation, or on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Jeremy Hsu is science writer based in New York City whose work has appeared in Scientific American, Discovery Magazine, Backchannel, Wired.com and IEEE Spectrum, among others. He joined the Space.com and Live Science teams in 2010 as a Senior Writer and is currently the Editor-in-Chief of Indicate Media. Jeremy studied history and sociology of science at the University of Pennsylvania, and earned a master's degree in journalism from the NYU Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. You can find Jeremy's latest project on Twitter.