Milky Way's Color Is White As a Morning's Snow

Our galaxy is aptly named the Milky Way — it looks white, the color of fresh spring snow in the early morning, scientists now reveal.

Color is a key detail of galaxies, shedding light on its history of star formation. Unfortunately, since we are located well within our galaxy, clouds of gas and dust obscure all but the closest regions of the galaxy from view, keeping us from directly seeing what color our galaxy is as a whole.

"We can really only see 1,000 to 2,000 light-years in any direction — the Milky Way is 100,000 light-years across," said study co-author Jeffrey Newman at the University of Pittsburgh. "The problem is similar to determining the overall color of the Earth when you're only able to tell what Pennsylvania looks like."

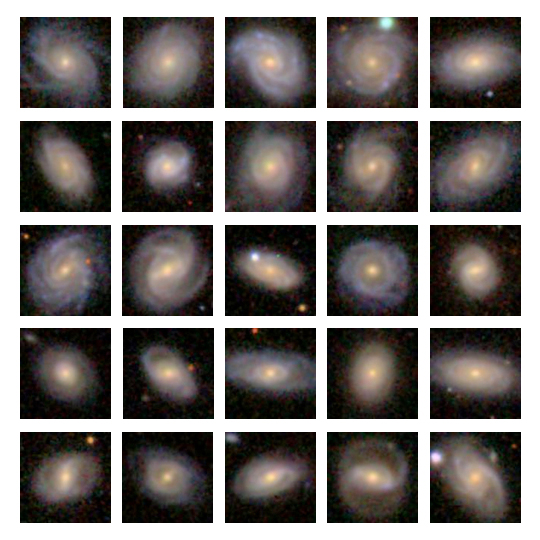

To sidestep this problem, astronomers decided to look at other galaxies' colors to figure out the hue of our own. The reasoning is that galaxies whose other properties closely match the Milky Way's likely can tell us what our galaxy's color is.

What color, the Milky Way?

The scientists relied on the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, which measured the detailed properties of nearly a million galaxies, collecting color images of about a quarter of the sky. They focused on the hundreds of galaxies that were similar to the Milky Way in terms of their total amount of stars and the rate at which they are creating new stars, both related to the brightness and color of a galaxy.

They found on average, the best match for the Milky Way's color was "fine-grained new spring snow seen in the early morning light, about an hour after dawn," Newman told SPACE.com. "If you were outside the Milky Way, it'd look white to you. The Milky Way has a very appropriate name."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Newman composed a haiku for the discovery. "Look at new spring snow; see the river of heaven; an hour after dawn," he recited.

Specifically, "the color temperature is that of a 4,840 Kelvin light bulb," Newman said. "It's bluer than incandescent lights, which are 3,000 Kelvin, and redder than the white on a TV or noonday light, which is 6,500 Kelvin."

Clues to star formation

The fact that the Milky Way is right on the dividing line between what scientists would call red galaxies that rarely form new stars and blue galaxies where stars are still being born suggests that formation of new stars in the Milky Way must be winding down, Newman said.

"A few billion years from now, our galaxy will be a much more boring place, full of middle-aged stars slowly using up their fuel and dying off, but without any new ones to take their place," Newman said. "It will be less interesting for astronomers in other galaxies to look at, too — the Milky Way's spiral arms will fade into obscurity when there are no more blue stars left."

Newman and his colleagues detailed their last week at the annual meeting of the 219th meeting of the American Astronomical Society.

Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us