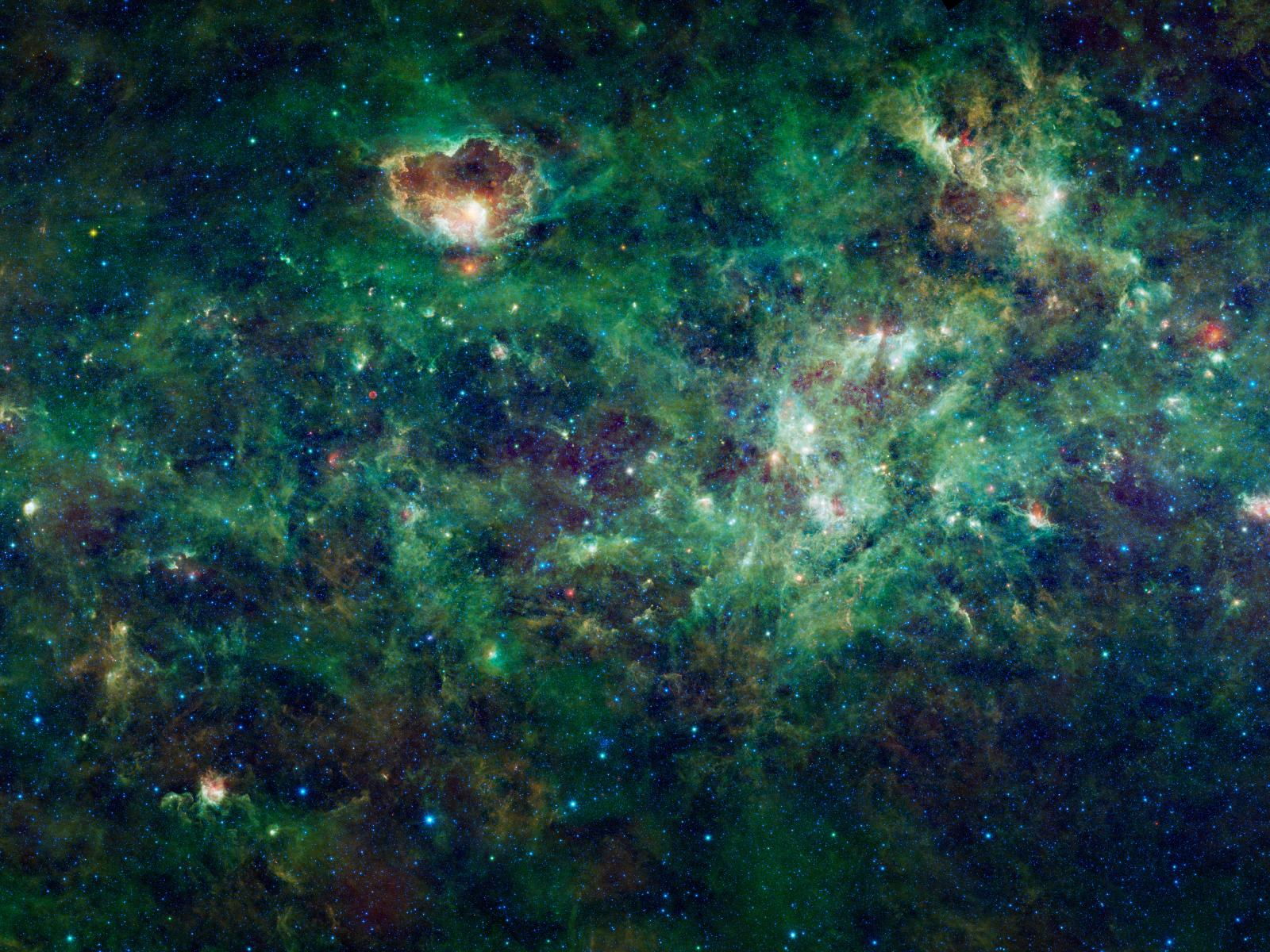

Space Bubbles Offer Glimpse at Our Sun's Evolution

Bubbles full of stars are now shedding light on how our sun and its siblings might have formed, scientists find.

Stars like our sun likely formed in clusters associated with massive stars. These huge stars are thought to form in the centers of giant clouds of cold gas maybe a million times the mass of our sun, with the hot winds these massive stars give off carving out bubbles within these clouds.

"Almost all the stars in the galaxy formed in hot bubbles where huge stars formed," said the study's lead author, Xavier Koenig, at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center.

How other stars like our sun formed next, however, remains debated. One idea, dubbed the "collect-and- collapse" model, suggested that by pushing matter outward, the hot winds from massive stars eventually compress enough material at the outer regions of these clouds to form into stars.

Another concept, dubbed the "chain-reaction" model, suggests that by slamming into matter, the hot winds immediately generate stars from the core of the cloud outward, resulting in what look like pillars and mountains of stars, Koenig said.

To see which of these models might be correct, astronomers relied on data from NASA'sWide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) space telescope, which mapped the entire sky twice in infrared light. The researchers concentrated on a number of star-forming clouds or nebulas.

"Young stars are a little bit brighter in the infrared than the sun," Koenig said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The researchers noticed patterns in how newborn stars were arranged in space within these nebulas. The way these were seen sprinkled within the bubbles in these clouds suggests they formed via the chain-reaction model.

"WISE shows how stars burst onto the scene," Koenig said.

Although these findings strongly favor the chain-reaction model, "you can't rule out the other model," Koenig told SPACE.com. Stars in other nebulas could form via the collect-and-collapse model, depending on their initial conditions. "What we'd like to do is set up a theoretical picture for how often that might happen," he said.

NASA's launched the WISE space telescope in December 2009. The $320 million space observatory spent more than a year mapping the sky in infrared wavelengths before shutting down for good in February 2011. During its mission, WISE scanned the sky twice and snapped more than 1.8 million images of asteroids, stars and galaxies.

Astronomers are still gleaning new discoveries from the staggering wealth of imagery recorded by the spacecraft. WISE also discovered 19 previously unknown comets and more than 33,500 asteroids.

The scientists detailed their findings Jan. 10 at the 219th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Austin, Texas.

Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us