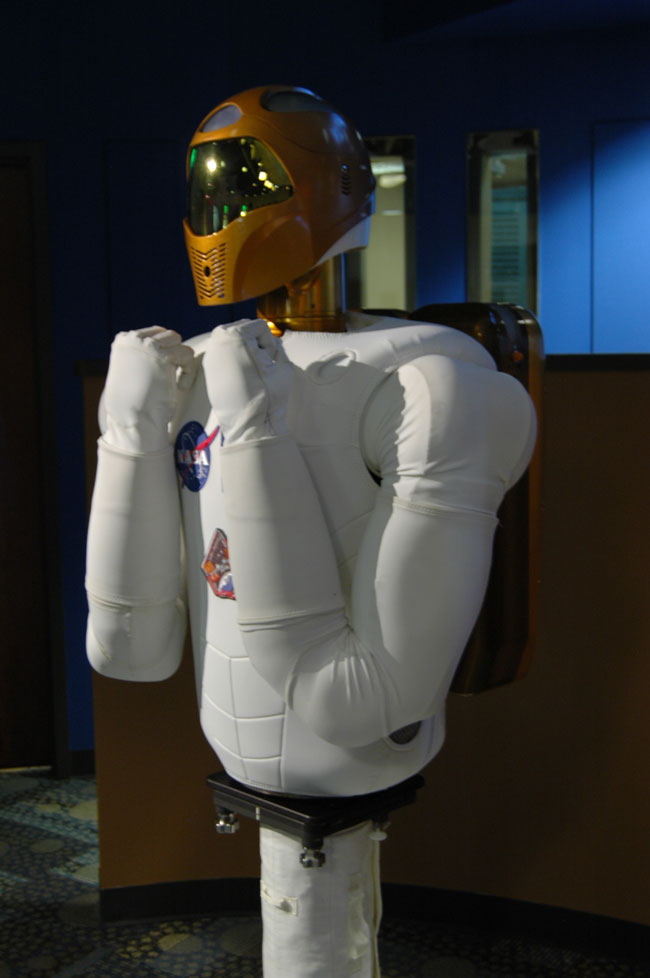

Humanoid Robot Hitching Space Ride on Shuttle Discovery

HOUSTON – After 15 years of preparation, the first human-like robot designed for use in space is ready for launch.

The robot helper, called Robonaut 2, is packed in a box-within-a-box and cushioned with foam for its trip on the space shuttle Discovery scheduled to launch Nov. 1.

The humanoid robot, which resembles the torso, head and shoulders of a person, was designed by NASA and General Motors to work alongside astronauts to complete chores and repairs aboard the International Space Station. [Gallery: Robonaut 2: Robot Butler for Astronauts]

Eventually, NASA officials envision these helper robots could be sent into situations deemed too risky for humans.

The humanoid robot has even taken the Twitter world by storm. NASA's robot handlers have been posting messages for the space automaton under the name @AstroRobonaut since late July.

Robots in space

Once aboard the space station, the $2.5 million Robonaut 2 will be tested to be sure it works as expected in the zero gravity environment. Over the next year, the Robonaut 2's developers hope to test the robot on a variety of tasks, including handling flexible fabrics and possibly helping out with some light housework.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The challenge we accepted when we started the Robonaut project was to build something capable of doing dexterous, human-like work," Rob Ambrose, the acting chief of the Automation, Robotics and Simulation Division at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, told reporters Thursday (Oct. 21). "From the very beginning, the idea was the robot had to be capable enough to do the work but at the same time be safe and trusted to do that work right next to humans."

Robonaut 2's dexterity sets it apart from other robots. In addition to its human-like fingers, the machine has soft palms that can grasp and envelop objects. It is also a "soft" robot, Ambrose said.

Metal or steel appendages could nick or scratch tools, potentially creating a hazard if an astronaut later picked up the same tool and tore his or her glove. As a result, Robonaut 2 is padded all over to prevent that from happening.

The robot's sensors are also designed with safety in mind. If the robot feels an unexpected object (like an astronaut's head) in its way, it is programmed to stop its movement. Or, if something hits Robonaut 2 with enough force, the robot will immediately shut down.

Cold storage on space station

Robonaut 2 will likely stay in its foam-filled box until late December or early January, Ambrose said. It will take a few hours to unpack the robot and just a few minutes to boot it up using a laptop-like console. After incrementally testing various parts, the developers plan to begin giving the robot easy tasks, eventually programming it to carry out more complex goals.

Two potential uses they would like to start testing include having the robot wipe down handrails and vacuum air filters – two tedious tasks that station astronauts are currently required to complete.

For now, Robonaut 2 is just an upper body, so it will remain stationary inside the U.S. laboratory module. In the future, the robotics team plans to test different lower bodies that will allow Robonaut 2 to maneuver around, inside and even outside the space station.

The launch "might be just a single step for this robot," Ambrose said. "But it's really a giant leap forward for a tin man."

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Space.com sister site Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.