New Star Discoveries Found in Antique Telescope Plates

A century's worth of astronomical photographic plates have revealed a slew of new variable stars, many of which alter on timescales and in ways never before seen.

The discoveries come from a new analysis of the 500,000 plates made by the Harvard College Observatory from the 1880s through the 1980s, covering the whole sky. The trove of old-school data has offered astronomers an unprecedented look at how stars change over long timescales.

"The Harvard College observatory has the most wonderful, best collection [of photographic plates] in the world," said Harvard graduate student Sumin Tang, who works on the plate analysis program. "It's a very unique resource because it's over 100 years. No other data set could do this."

Blast from the past

The plates are relics from an earlier era, when researchers used glass surfaces coated with light-sensitive silver salts to record the visions seen by telescopes. The Harvard collection includes plates made with dozens of telescopes.

Starting in the 1990s, photographic plates were replaced with more sensitive CCDs (charge-coupled devices), which are digital light sensors. Smaller versions of these same devices power digital cameras. [Truth Behind the Photos: What the Hubble Space Telescope Really Sees]

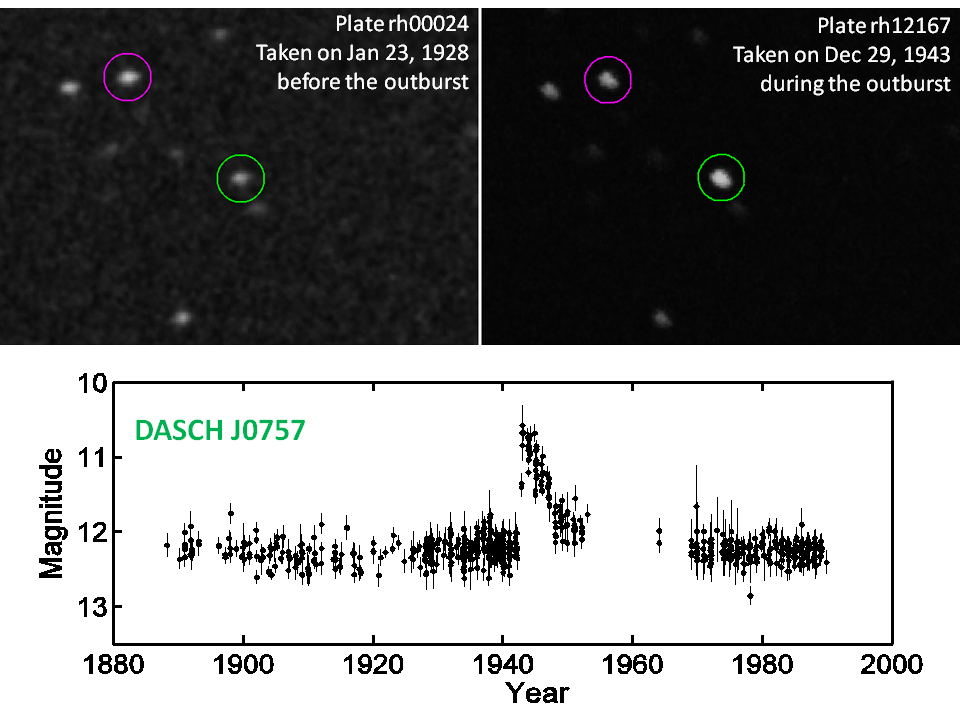

Now scientists are trying to digitize the plate collection, basically using CCDs to image the plates, then applying an algorithm to quantify how bright stars appear and search for variations over time. The project, called Digital Access to a Sky Century@Harvard (Dasch), is headed by Harvard astronomer Jonathan Grindlay.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"In this way we can perform a systematic search for long-term variables," Tang told SPACE.com. "We don't need to use our eyes, because it would take forever."

Most of the stars in the plate collection were imaged between 500 and 1,500 times, providing ample evidence for some weird stellar behavior. So far, only 4 percent of the plates have been digitized, but that data set alone has turned up some new finds. The team hopes to digitize the whole collection over the next three to five years.

So far, though, the initial data yielded "wonderful results," Tang said. Some of the stars caught on the plates brighten and dim gradually for reasons unknown. "We've found several different new types of variables," she added.

Strange variables

For example, the astronomers discovered a group of stars that all vary in the same, weird way. These stars all happen to belong to a class called K giants, with temperatures of about 4,400 Kelvin (7,500 degrees Fahrenheit, or 4,100 degrees Celsius). Over decades they become brighter and dimmer by a factor of two.

"This kind of timescale is weird because it's just too long," Tang said.

The researchers think the stars can actually be divided into two classes: binary (double star) systems, and single stars, with two different mechanisms behind their variations.

The binary variables are possibly caused by strong magnetic activity stimulated by interactions between the two stars. "The other group, the single ones, are even more exotic," Tang said. "We guess it might be related to some gas processes. There must be something weird happening, but we don't know. That's the fun part."

Another weird set of variable stars discovered in the data are called symbiotic stars, which are pairs of stars where one is hot and the other cold — for example, a red giant and a white dwarf star orbiting each other. Some process is causing some of these star systems to alter in brightness over decades, but astronomers aren't sure what. They suspect the phenomenon might be related to nuclear burning of hydrogen on the surface of the white dwarf star, or accretion of mass onto one of the stars.

Ultimately, the researchers hope the project reveals much more about how stars evolve over time.

"Astronomy is driven by observation," Tang said. "If you have unique data, you will make unique discoveries, there's no doubt about that."

Tang presented some of the new findings earlier this month at the 219th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Austin, Texas.

The project is supported by the National Science Foundation and the Cornel and Cynthia K. Sarosdy Fund for DASCH.

You can follow SPACE.com assistant managing editor Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.