Damaged Russian Spaceship Forces Big Launch Delay for Next Station Crew

A botched pressure test of a Russian space capsule slated to launch the next crew to the International Space Station has forced NASA and its partners to delay the planned liftoff for more than a month.

The Russian Soyuz spacecraft launch was originally slated for March 29, but now is targeted for no earlier than May 15, NASA's International Space Station program manager Mike Suffredini told reporters today (Feb. 2).

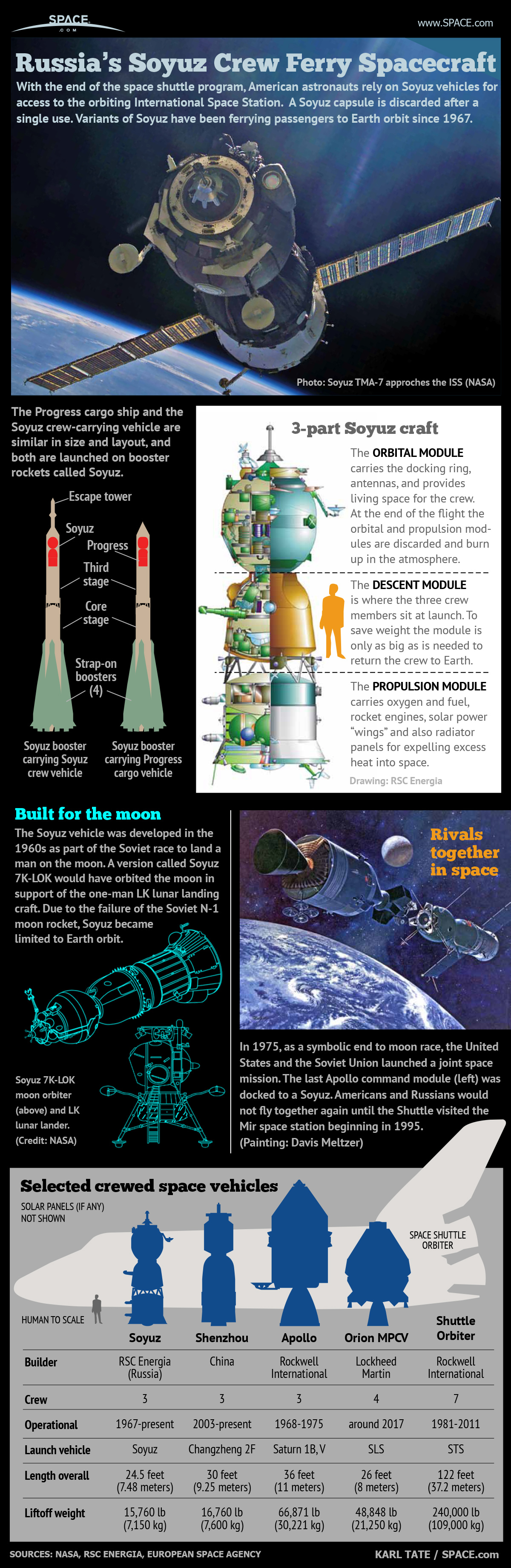

The Soyuz's crew capsule, one of three modules that make up the entire Soyuz TMA-04M vehicle, has been scrapped after an accident during testing caused it to spring a leak in one of its descent module's rocket thruster fuel tanks. Now Russia's main space contractor, RSC Energia, is readying the next spaceship on the line, though the issue will cause a lengthy delay.

"This particular event is very unfortunate, but you know this is a complicated business and things happen," Suffredini said. "To me this is not indicative of some overarching problem at the Energia corporation. I have every confidence that they'll figure out the cause of this and rectify it for the future." [Russia's Manned Soyuz Space Capsule Explained (Infographic)]

With the retirement of NASA's space shuttle fleet last year, Russia's three-person Soyuz space capsules are currently the only vehicle available to ferry American astronauts to and from the International Space Station. NASA plans to eventually use private U.S.-built commercial spacecraft to transport crews and cargo to the station, but those new vehicles are still years away from being ready.

Meanwhile, NASA is contemplating another delay — in this case, of the unmanned SpaceX Dragon capsule's inaugural trip to deliver supplies to the space station. The private spacecraft was due to make its first test launch to the orbiting laboratory on Feb. 7, but Suffredini said the latest target date is March 20, and even that might be a stretch, as the vehicle still requires more testing and some minor fixes.

Space station hang time

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The faulty Soyuz capsule was slated to carry NASA astronaut Joe Acaba and Russian cosmonauts Gennady Padalka and Sergei Revin up to the space station to begin long-duration stays.

They were due to replace three of the Expedition 30 spaceflyers currently living on the outpost: NASA astronaut Dan Burbank and Russian cosmonauts Anton Shkaplerov and Anatoly Ivanishin.

However, because of the Soyuz issues, NASA and Russia have decided to extend the current crew's mission to keep the space station running smoothly. Those three were scheduled to return to Earth March 16, but now will come home April 30.

The delay is also likely to cause rippling setbacks in other planned launches and landings later this year.

"We probably won't see the next Soyuz until the mid-July timeframe," Suffredini said. "There'll be about a two-week impact as we go into the fall and winter. Although there is a schedule impact, from a performance standpoint there's really no impact" to operations on the station. [Video: Soyuz Rocket's Bumpy Ride — The History]

Under pressure

The Soyuz problem occurred during pressure testing of the Soyuz's descent module and part of its propulsion module.

The bell-shaped descent module seats the Soyuz crew during launch and landing and is located between the propulsion and orbital modules. It is the only part of the Soyuz that returns to Earth. The propulsion and orbital modules are discarded during re-entry.

"Right before they ship the spacecraft, they do a pressure test where they over-pressurize the vehicle because it's designed to handle more than normal pressure, and then they hold that pressure for a while, and if it holds that pressure you consider it a success," Suffredini said. "In the process of doing that it was exposed to a pressure that is substantially higher than what they had planned."

This elevated pressure caused deformations on part of the spacecraft, prompting some of its welding joints to leak.

Since the spacecraft wasn't designed to handle these pressure loads, the total repercussions to the hardware were unknown, and officials decided to ditch the vehicle altogether rather than attempt to repair it.

Latest in a string of failures

The issue comes after a string of disappointments for Russia's space agency.

In November, its Mars probe Phobos-Grunt failed after launch, and subsequently crashed into the ocean.

Perhaps even more worrying, a Russian Soyuz rocket carrying an unmanned Progress cargo freighter to the space station failed after its launch, resulting in the loss of the vehicle.

That booster was similar enough to the ones Russia uses to loft people to orbit that NASA and Russia delayed the scheduled manned liftoffs until the cause of the accident had been determined and fixed.

"Our Russian colleagues have had a number of challenges last year relative to launches and they've taken that very seriously and are trying to look for any consistent clues across the board," Suffredini said. "Compared to the human spaceflight side, I can tell you from a booster standpoint, they do treat the human vehicles completely differently."

Ultimately, he said, the business is risky.

"Even the most reliable systems sometimes give you challenges, but I think they're addressing them," Suffredini said.

You can follow SPACE.com assistant managing editor Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.