Proposed budget cuts are forcing NASA to suspend plans for ambitious, expensive missions to destinations throughout the solar system.

The White House's budget request for 2013, which was released Monday (Feb. 13), keeps overall NASA funding flat but allocates just $1.2 billion to the space agency's planetary science program. That's a 20 percent cut from the current allotment of $1.5 billion, and further reductions are expected over the next several years.

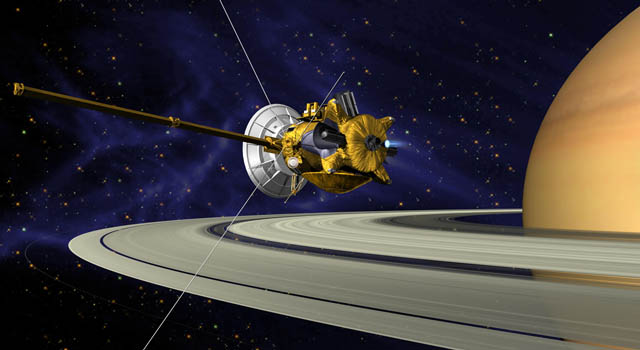

NASA officials say this funding picture leaves no room for multibillion-dollar "flagship" planetary missions — a departure for the space agency, which has launched roughly one such effort per decade since the 1970s. Those missions include the Cassini spacecraft's study of the Saturn system and the so-called Grand Tour of the solar system by the twin Voyager spacecraft.

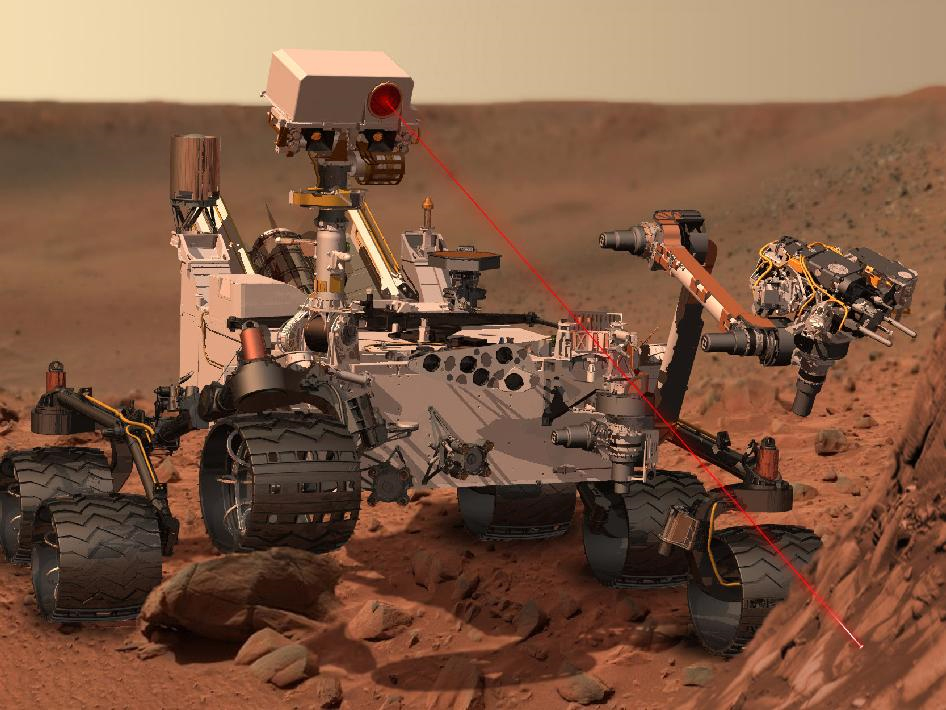

So for the moment, there are no plans to develop more planetary flagships beyond the $2.5 billion Mars Science Laboratory (MSL), which will drop the 1-ton Curiosity rover onto the Martian surface this August to investigate the Red Planet's potential to host life as we know it. NASA launched MSL last November.

"There is no room in the current budget proposal from the president for new flagship missions anywhere," John Grunsfeld, NASA's associate administrator for science, told reporters Monday. [NASA's 10 Greatest Science Missions]

NASA is continuing to work on an astrophysics flagship mission, the James Webb Space Telescope. This huge instrument, billed as the the successor to the agency's Hubble Space Telescope, is slated to cost $8.8 billion and launch in 2018 at the earliest.

A history of planetary flagships

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

NASA divides its planetary exploration missions into three classes: Discovery, New Frontiers and Flagships. Flagships are the most ambitious and priciest of the three, with costs running into the billions of dollars.

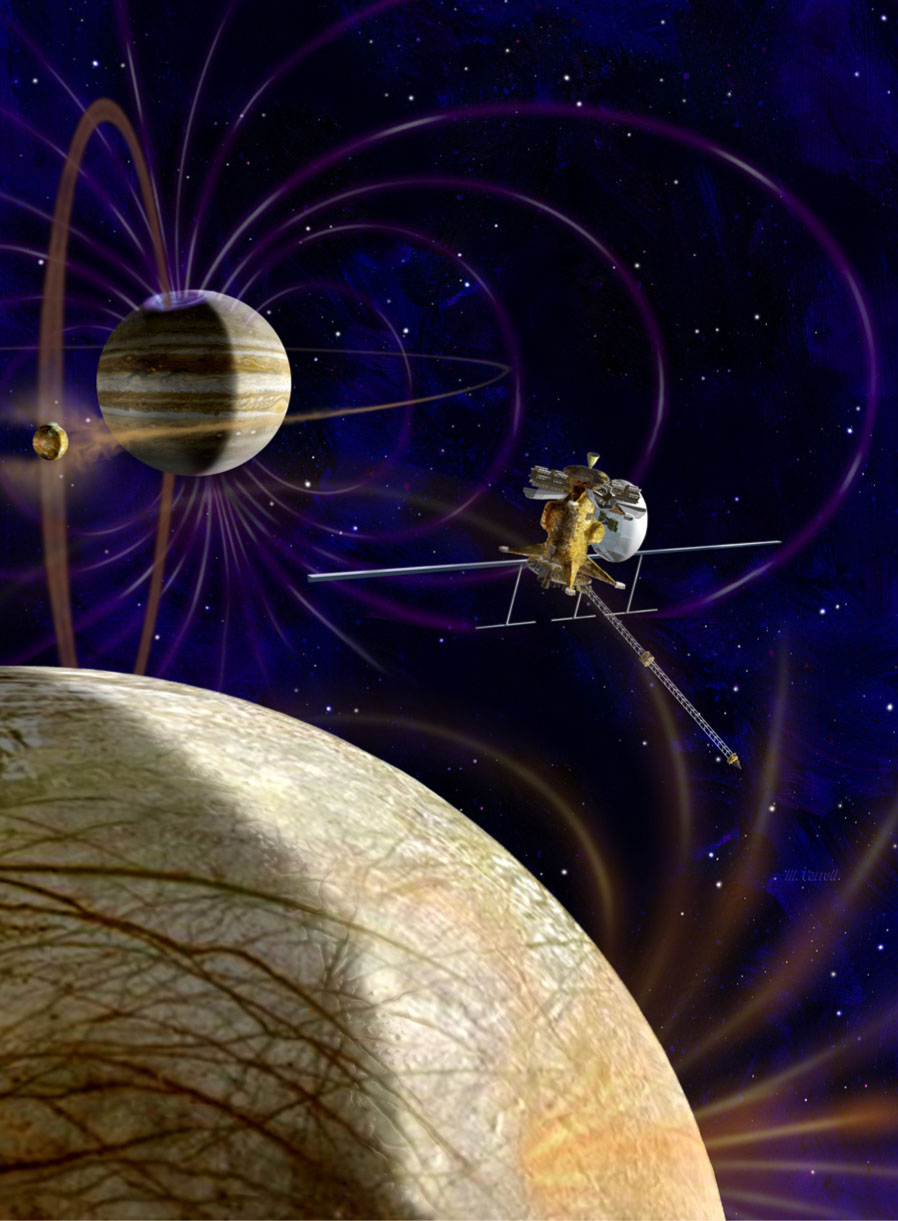

NASA has developed roughly one planetary flagship per decade, beginning with the Voyager mission to the outer solar system in the mid-1970s. The Galileo mission to study Jupiter and its moons followed in 1989, and in 1997, NASA launched Cassini toward the Saturn system.

The Curiosity rover is the most recent NASA planetary flagship, and perhaps the last for a while. Because of the proposed budget cuts, plans for possible future flagships — which include a Mars sample-return mission and a probe that would study Jupiter's ocean-hosting moon Europa — are on indefinite hold. [Infographic: NASA Planetary Science Takes a Hit]

"A flagship mission is not on the table," Grunsfeld said.

This state of affairs is deeply unsettling to some scientists and space-exploration advocates.

"People know that Mars and Europa are the two most important places to search in our solar system for evidence of other past or present life forms," Jim Bell, president of the nonprofit Planetary Society, said in a statement. "Why, then, are missions to do those searches being cut in this proposed budget? If enacted, this would represent a major backwards step in the exploration of our solar system."

Bill Nye, CEO of the Planetary Society and host of the former TV show "Bill Nye the Science Guy," voiced similar sentiments.

"We are on the verge of finding habitable environments on Mars and other worlds. These discoveries will change the world," Nye told SPACE.com via email. "Curtailing this work now will lead to spacecraft that don't work right, missions that crash, and the dissipation of the remarkable aerospace workforce. It may well lead to other space agencies taking on the search for life, and finding it, albeit decades hence."

Still exploring

The proposed budget cut compels NASA to drop out of the European-led ExoMars missions, which aim to launch an orbiter and a drill-toting rover toward the Red Planet in 2016 and 2018, respectively. These two missions are viewed as key steps toward an eventual Mars sample-return effort.

However, NASA officials stress that the agency is not giving up on planetary exploration in the near future. It's just scaling down, focusing on missions that may cost $500 million to $700 million instead of several billion.

The space agency is looking into sending such a "medium-class" mission to Mars in 2018 or 2020, Grunsfeld said. The details of this pending effort have yet to be worked out, and won't be until NASA finishes overhauling its Mars exploration strategy — another move the agency is undertaking in response to the budget cut.

And NASA isn't abandoning flagships forever. Agency scientists and managers will keep laying the foundations necessary to enable ambitious missions, so they'll be ready to hit the ground running should the fiscal environment improve, Grunsfeld said.

Grunsfeld said he hopes NASA can return Mars rocks to Earth for study by 2030 or so, and he also expressed optimism about potential flagships to destinations beyond the Red Planet.

"We're still doing mission studies for Europa. We still have folks thinking about Uranus," Grunsfeld said. "We're still working forward so that when we have the kind of budget that would enable us to start a flagship to the outer planets, we will do so."

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.