Switzerland Plans 'Janitor Satellite' to Clean Up Space Junk

Earth is surrounded by a cloud of more than half a million pieces of space junk, from bus-size spent rocket stages to tiny flecks of paint. Orbiting at breakneck speeds, every last bit poses grave dangers — and means huge insurance premiums — for operational satellites, and it threatens the International Space Station, too. Every time two orbiting objects collide, they break up into thousands more pieces of debris.

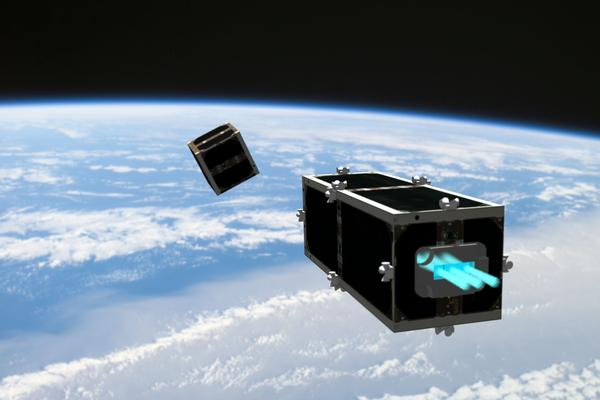

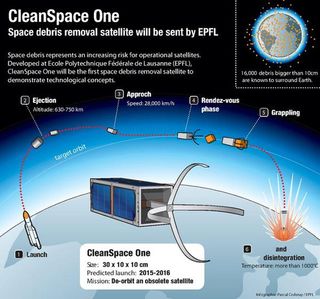

To combat this growing headache, Swiss scientists and engineers have come up with a solution: CleanSpace One, a project to build the first in a family of so-called "janitor satellites" that will help clean up space. The prototype space junk cleaner will be a rectangular satellite nearly 12 inches (30 centimeters) long and about 4 inches (10 cm) tall and wide.

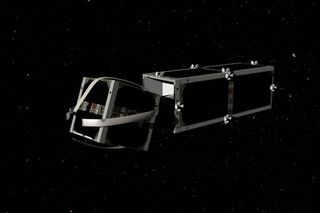

Slated to launch as early as 2015, CleanSpace One will rendezvous with one of two defunct objects in orbit, either the Swisscube picosatellite or its cousin TIsat, both 61 cubic inches (1,000 cubic cm) in size. When the janitor satellite reaches its target, it will extend a grappling arm, grab it and then plunge into Earth’s atmosphere, burning up itself and the space junk during re-entry.

CleanSpace One is being designed and built at the Swiss Space Center, part of the Swiss Federal Institute for Technology in Lausanne, or EPFL. Scientists there are developing the micro- and electric propulsion systems that will enable CleanSpace One to grab hold of space junk as the two objects zip around Earth at 17,500 mph (28,000 kph). [Video and images of CleanSpace One mission]

"The [main] challenge will be having a deployment either of a robotic arm or a deployment of a mechanism that will embrace or grab exactly Swisscube," EPFL scientist Muriel Richard said in a press video. The design team is drawing inspiration from the grabbing mechanisms of living organisms, she said.

Eventually, the team hopes to offer and sell a whole suite of ready-made systems designed to de-orbit space junk of various sizes "Space agencies are increasingly finding it necessary to take into consideration and prepare for the elimination of the stuff they're sending into space. We want to be the pioneers in this area," Swiss Space Center Director Volker Gass said.

Smaller systems like CleanSpace One will be low-cost, Richard said. "It's not a multimillion development, it’s a university based development."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

There may indeed be a market for such janitor satellites.

In 2009, the American Iridium satellite collided with debris from an inactive Russian satellite, producing roughly 2,000 more pieces of debris, some of which went on to destroy a satellite worth $55 million. The more junk accumulates, the more likely collisions between satellites and debris will become, with each collision causing a proliferation of debris.

"There’s going to be an avalanche effect and more and more satellites are going to be kicked out or destroyed in orbit," Gass said. Higher risk of impact means higher space junk insurance premiums, and the cost of insuring today’s active satellites is around $20 billion.

Falling space debris even poses a slight risk of injuring people on Earth.

Claude Nicollier, an astronaut and EPFL professor, compared the space junk problem with global warming. "In a way, there’s some similarity between the two problems," he said. "If we don't do anything, we’ll have big problems in the future."

This story was provided by Life's Little Mysteries, a sister site to SPACE.com. You can follow Life's Little Mysteries on Twitter (@LLMysteries) and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Natalie Wolchover was a staff writer for Live Science and a contributor to Space.com from 2010 to 2012. She is now a senior writer and editor at Quanta Magazine, where she specializes in the physical sciences. Her writing has appeared in publications including Popular Science and Nature and has been included in The Best American Science and Nature Writing. She holds a bachelor's degree in physics from Tufts University and has studied physics at the University of California, Berkeley.