By the middle of the decade, it may be possible to salvage satellites that run out of fuel or suffer minor malfunctions in orbit.

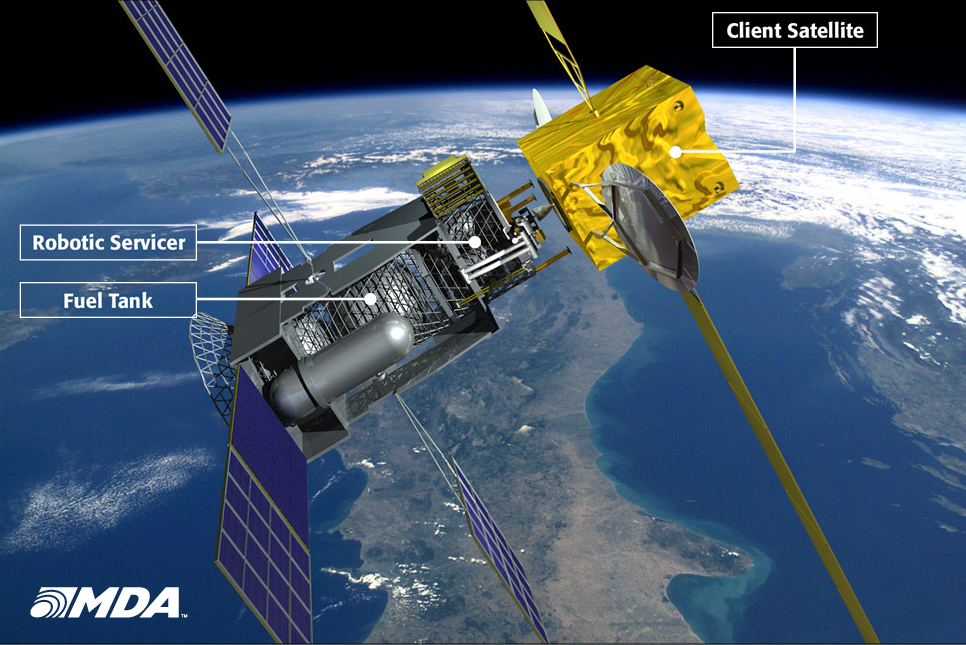

Canada-based aerospace firm MacDonald, Dettwiler and Associates Ltd. is designing a spacecraft that will serve as an orbiting gas station and mechanic. The robotic vehicle will be able to top off satellites' fuel tanks and perform minor repairs as needed. MDA's first servicing satellite could be ready to go by 2015 or 2016, if a suitable customer steps up, company officials said.

"The future for space servicing is definitely now," Dan King, director of orbital robotics at MDA, said during a presentation with NASA's Future In-Space Operations working group yesterday (Feb. 15). "The key technologies that are needed to do some fundamental operational-type services are here."

Extending satellites' lives

Currently, most satellites last only as long as their stores of onboard propellant allow. When a spacecraft runs out of fuel, it essentially turns into a very expensive piece of space junk, adding to the massive cloud of debris already clogging Earth orbit.

"The analogy is almost like, you drive your Ferrari and you throw away your Ferrari after running a single tank of gas," King said.

MDA wants to change this by developing a refueling spacecraft called the Space Infrastructure Servicing vehicle. The unmanned SIS would be an orbital mechanic as a well as a gas station attendant, using its robotic arm and tool kit to make minor repairs to stricken satellites. [Video: How the Refueling Satellite Will Work]

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The servicing spacecraft would be controlled from the ground, but it could operate with varying degrees of autonomy, depending on the characteristics of each mission, King said.

The SIS vehicle is designed to refuel and repair a variety of client satellites, ranging from commercial to governmental. The flying gas station would be about the size of a standard telecommunications satellite, but far more of its weight would consist of propellant, King said.

According to MDA's designs, when the SIS spacecraft itself runs low on fuel, a separately launched "tanker" would replenish its supply of propellant, allowing the vehicle to continue servicing satellites far into the future.

"We very much plan to have this as a sustainable and expandable-type service as well," King said.

MDA could launch its first SIS within three and half years, King added, so a servicing satellite could be operational by 2015 or 2016 — provided the company can find a customer.

A deal falls through

MDA thought it found that customer last year. In March 2011, satellite operator Intelsat agreed to pay $280 million over time for the SIS vehicle to refuel certain craft in its fleet. The maiden SIS mission was to fly in 2015.

However, the two companies announced last month that the deal is off.

"As with any contract, there are various time-based criteria that have to be met," King said. "And I guess we were not able to meet those datelines for the original plan, due to various factors."

One of those factors, King said, was a lack of clarity and commitment from the United States government. A show of support — or at least a better idea of where the government stands — could help jumpstart the satellite-servicing industry, he added.

"There is sufficient commercial-type market and demand to close the business case," King said. "But on the other hand, government-type investment at least needs to be clarified, as to what extent it's available and can help."

An idea whose time has come?

MDA isn't the only business or organization working to develop satellite-servicing technology. Aerospace firm Vivisat, for example, is designing a spacecraft called the Mission Extension Vehicle, which would dock to satellites and provide propulsion and attitude control.

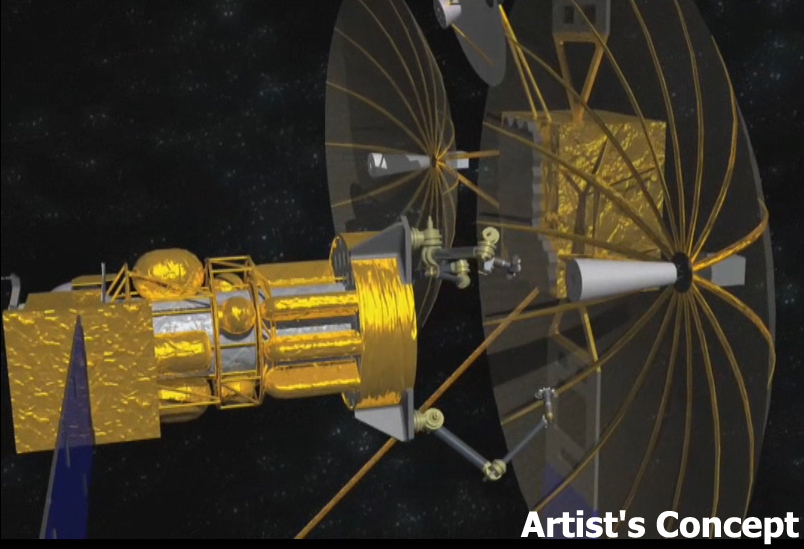

The U.S. military's Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency has started a program called Phoenix, which seeks to recycle still-functioning pieces of defunct satellites and incorporate them into new space systems for low cost.

Phoenix aims to use a robotic servicing spacecraft to snag still-working antennas from the many retired and dead satellites in geosynchronous orbit — about 22,000 miles (35,406 kilometers) above Earth — and attach them to smaller "satlets," or nanosatellites launched from Earth.

And next month, NASA will begin the first tests of its Robotic Refueling Mission, an experiment that was delivered to the International Space Station on the final space shuttle flight in July 2011. RRM will serve as a trial for the orbiting lab's twin-armed Dextre robot, testing the ability to refuel and otherwise maintain satellites in space.

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.