Humanity can keep its space-junk problem under control by removing about five big pieces of orbital debris every year from the huge cloud surrounding Earth, experts say.

Such an active remediation effort, combined with more passive measures like draining fuel from defunct satellites, would likely keep space-junk levels relatively constant for the next 200 years or so. And there's more good news: We probably have a decade or two to figure out how to do it, researchers say.

"Orbital debris is a serious issue, but at the same time, the sky is not falling," J.-C. Liou, of NASA's Orbital Debris Program Office in Houston, said during a presentation with the agency's Future In-Space Operations working group Wednesday (Feb. 22).

"I think we can continue to manage the current environment for some time — maybe 10 years or 20 years — before we have to consider debris removal to better preserve the environment for future generations," Liou added. [Worst Space Debris Events of All Time]

A growing cloud of space junk

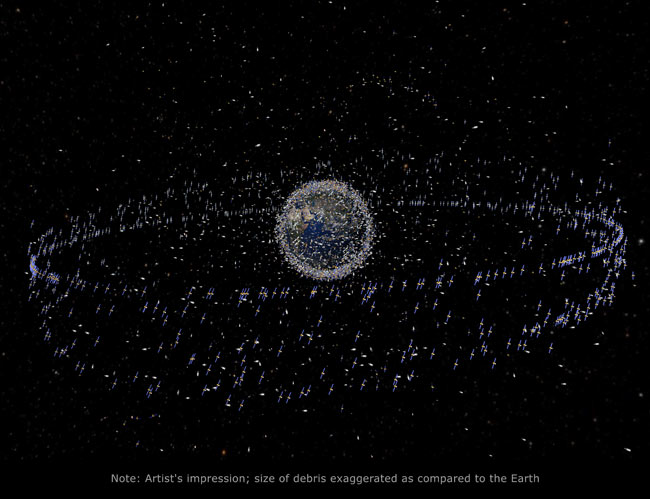

Earth is surrounded by a gigantic cloud of debris — stuff like spent rocket bodies, dead spacecraft and the fragments generated when these objects collide.

NASA estimates that this cloud contains about 22,000 pieces as large as a softball and 500,000 bigger than a marble. The number of pieces at least 1 millimeter in diameter probably runs into the hundreds of millions, Liou said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

All of this junk poses a threat to the 1,000 or so operational satellites currently zipping around our planet, as well as the International Space Station and other crew-carrying craft.

"The typical impact velocity in low-Earth orbit is about 10 kilometers per second [22,300 mph], and because of that, even a sub-millimeter debris could be a problem for human spaceflight and for robotic missions," Liou said.

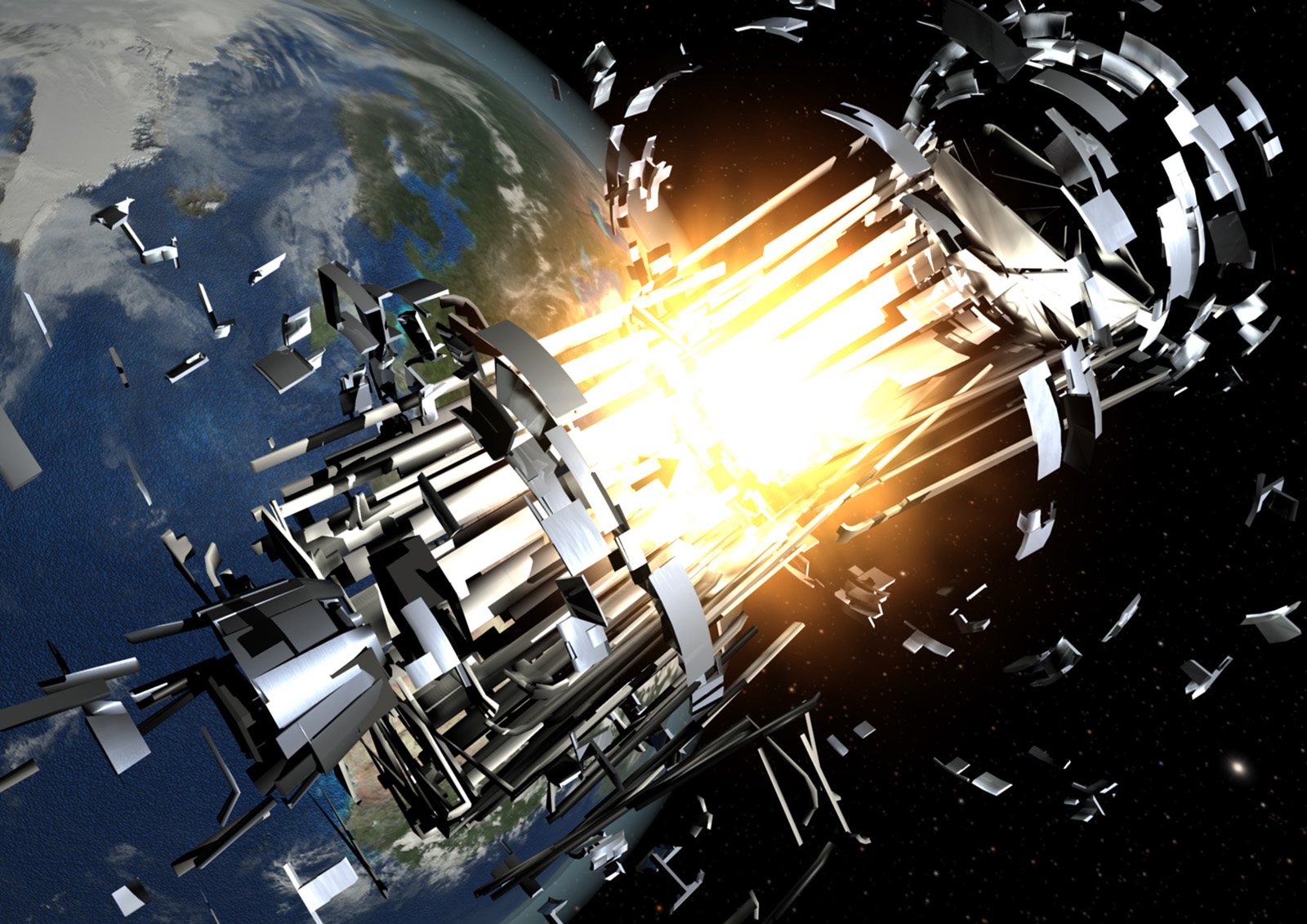

Many researchers think the amount of space junk around our planet has reached a critical threshold. There's now so much of the stuff that collisions will generate a continual, ever-escalating cascade, causing the debris cloud to keep growing even if humanity grounds all of its rockets.

One such collision occurred in 2009, when the Iridium 33 communications satellite slammed into a defunct Russian satellite. The cosmic smashup spawned more than 2,000 new large debris fragments, and many more too small to be tracked and catalogued.

Action needed

The international space community has devised some strategies in an attempt to mitigate the space-junk problem. Toward the end of a satellite's life, for example, operators are supposed to burn off any remaining fuel and discharge batteries to render the spacecraft less explosive.

But mere mitigation likely won't be enough, according to Liou.

"There is a need for a more aggressive measure to protect and preserve the environment," he said. "The time has come for us to consider active debris removal."

A modeling study Liou published last year suggests that active removal, combined with standard mitigation measures, could help reduce collisions and keep our space-junk cloud from cascading out of control.

If humanity pulled five large objects out of low-Earth orbit — which extends to roughly 1,240 miles (2,000 kilometers) above the planet's surface — every year starting in 2020, debris levels in 2210 would remain roughly where they are today, the study found.

Suitable targets for removal include old rocket bodies and dead satellites, because they're massive and numerous. Liou recommends against going after satellites initially; they're a diverse bunch in both size and structure, so it would be relatively tough to design a system capable of grappling many of them.

Rockets are a better first choice, Liou said. He suggests starting with spent Russian SL upper stages, which make up much of the orbital debris population. These rocket bodies weigh up to 8.9 metric tons, and their uniform structure would make them relatively easy to handle.

Roughly 62 percent of the 2,700 metric tons of debris in low-Earth orbit were launched by Russia or its forerunner state, the Soviet Union, Liou said.

An international problem

It's a good thing humanity has a decade or two to work on debris removal strategies, because no system is ready to go at the moment.

Researchers have lots of ideas, from nudging space junk out of orbit using ground-based lasers to launching spacecraft that would corral dead satellites with giant nets. But it will take more time, money and testing to develop and vet such technologies. [Photos: Space Debris Cleanup Concepts]

Meaningful debris removal will also take a great deal of international cooperation. The Russians still own those SL upper stages, for example, so the United States can't just go up and grab them without getting the go-ahead from Moscow.

Acting unilaterally could be destabilizing on its face, since some nations would doubtless regard a device capable of de-orbiting space junk as a potential space weapon. If it works on a dead satellite, after all, it may well work on an operational one as well.

For all of these reasons and more — including the scope and cost of any removal effort — the world will probably have to tackle the space junk issue together.

"This is an international problem," Liou said. "We cannot do this by ourselves."

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.