SAN FRANCISCO — Scientists have known for nearly 500 years that Earth isn't the center of the universe, but artists still haven't gotten the message.

Nicolaus Copernicus' "On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres," first published in 1543, showed conclusively that our planet orbits the sun. The seminal work laid waste to long-dominant Ptolemaic thought, which stated that everything in the cosmos revolves around our uniquely favored blue-green orb.

But artists still cling to the Ptolemaic view, glorifying humanity and asserting its exceptionalism with every brushstroke and finely wrought sentence. Experimental philosopher Jonathon Keats thinks it's time for that to change; he's pushing for a Copernican revolution in the arts.

"The arts have preached all about being universal, about being profound, for as long as anyone can remember, and yet that paradigm shift into something that genuinely is profound and genuinely is universal hasn't yet taken place," Keats said. "So I decided I would foment a revolution."

A Copernican art manifesto

Recent discoveries are highlighting just how ordinary our home planet may be. Astronomers have now found more than 700 worlds beyond our solar system, and thousands more await confirmation by follow-up observations. [The Strangest Alien Planets]

A recent study estimated that our Milky Way galaxy harbors at least 160 billion planets, many of them potentially Earth-like. And our galaxy is just one of hundreds of billions scattered throughout the known universe.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Great art is supposed to impart deep truths about humanity and its place in the universe. By that measure, art as it's practiced today is failing to deliver, according to Keats. For art has yet to embrace the mediocrity at the root of our existence, instead prioritizing self-expression and prizing the masterpiece above all.

But Keats has ideas about how to get art more in line with science. He has formulated a Copernican art manifesto, which consists of eight edicts:

- Painting must have the average color of the universe. Let it be beige.

- Sculpture must have the predominant composition of the universe. Let it be gaseous.

- Music must have the gross entropy of the universe. Let it be noisy.

- Architecture must have the fundamental geometry of the universe. Let it be flat.

- Cuisine must have the cosmological homogeneity of the universe. Let it be bland.

- Film must have the mathematical predictability of the universe. Let it be formulaic.

- Dance must have the characteristic motion of the universe. Let it be random.

- Literature must have the narrative arc of the universe. Let it be inconclusive.

Mediocrity on display

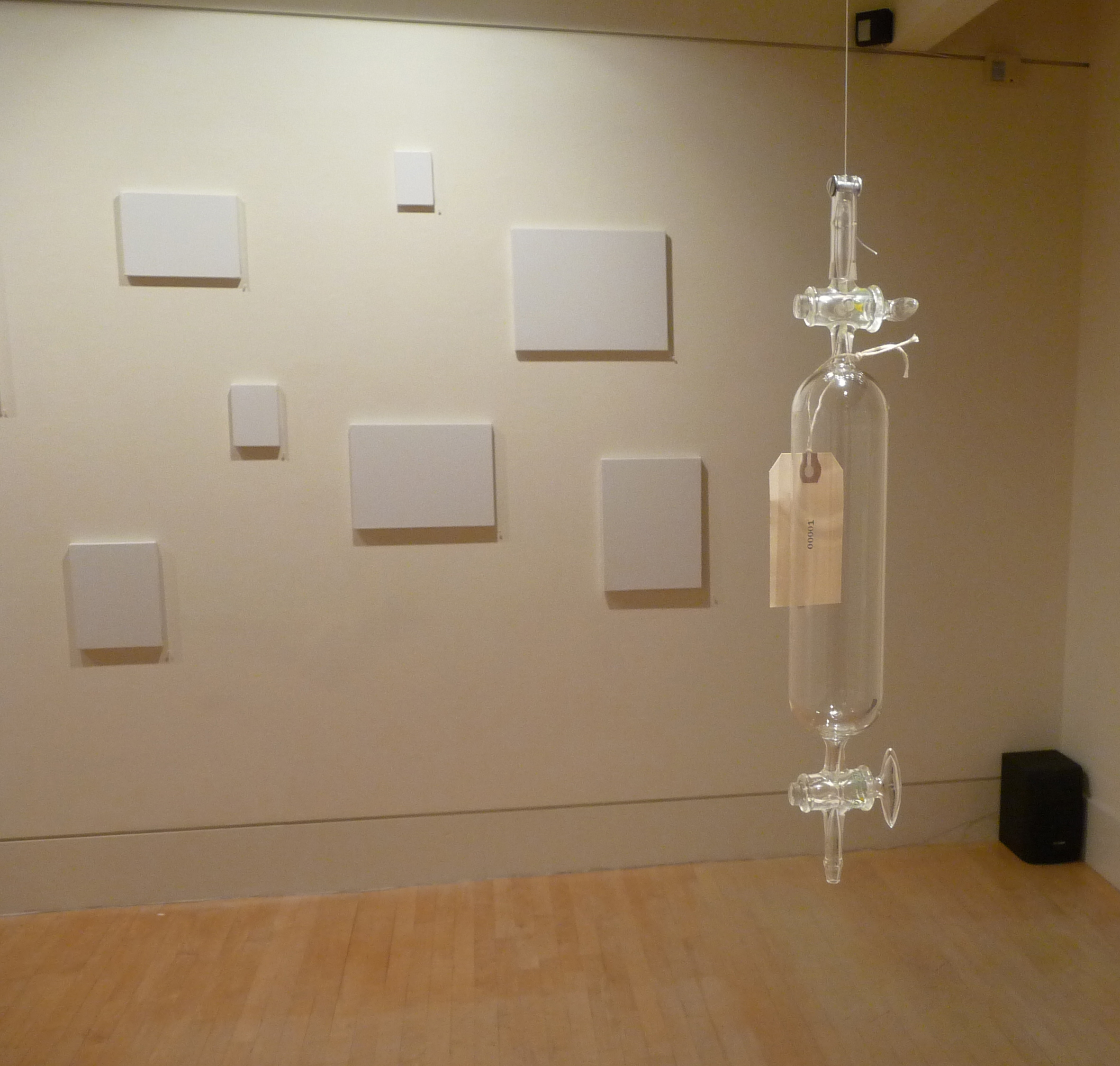

Some of these precepts were on display at recent exhibition of Keats' work, held at the Modernism Gallery here.

A dozen small rectangular paintings hung on the gallery's rear wall, for example, each one a monochrome beige that Keats said matches the average spectrum of starlight from 200,000 galaxies. He used housepaint bought at Ace Hardware, applying it in a flat coat.

"They weren't that easy," Keats told SPACE.com at the gallery, referring to the paintings. "I don't paint, including houses, so I had no idea. You know, your hands get sticky."

Several small glass tubes hung from the ceiling, one-time repositories for "sculptures" Keats created out of hydrogen gas. He had released the gas earlier in the evening, and now the artwork was diffusing throughout the building and beyond.

"People are going to experience this sculpture who have no idea," Keats said. "They might even incorporate it into themselves."

'Copernican' cuisine and music

Keats also brought several dozen canisters of his "Universal Anti-Seasoning," a cornstarch-based substance designed to modulate gustatory experience.

"This condiment diminishes flavor and texture to make any dish as homogeneous as the cosmos," the product's label reads.

The show had its own soundtrack, too, which was tweaked to match the entropy of the universe. Keats randomized 25 percent of the notes in Johann Sebastian Bach's "Well-Tempered Clavier," because, he said, the universe is one-quarter of the way to "heat death," or total disorderliness.

This erratic score looped endlessly in the background at the gallery, but Keats pooh-poohed the possibility that it might be driving him batty.

"I was already pretty far gone before the music even started," he said. "That's the great pleasure of working in this vein, is that you can let yourself go into these realms that are not generally excusable in society."

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.