Many Solar System Comets May Be Sun's Stolen Goods

At least 5 percent of the comets orbiting our sun may have been stolen from other stars, scientists say.

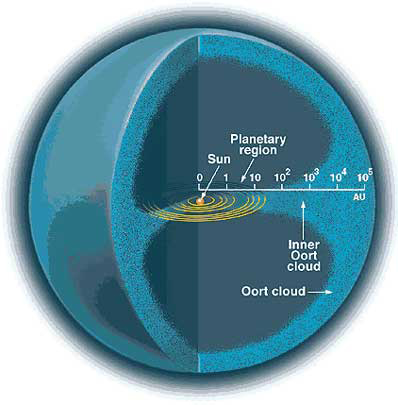

Our solar system is thought to include trillions of comets — small chunks of rock and ice — that circle the sun in a spherical swarm called the Oort cloud, a region that extends about 100,000 times the distance from the Earth to the sun in any direction. The average distance between the Earth and sun is 93 million miles (150 million kilometers).

Now scientists suggest that many of these bodies may actually have originated around other stars and were snatched up by the sun's gravity during a close swipe sometime over the past 4 billion years.

Astronomer Stephen Levine of Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Ariz., and undergraduate student Catherine Gosmeyer of Indiana University created a computer simulation to calculate how often stars would be likely to exchange comets when they passed close by each other, as stars often do in the course of their lives orbiting the center of the galaxy. [Photos of Halley's Comet Through History]

"It turns out it's much more frequent than in fact even I would have guessed," Levine told SPACE.com.

By looking at the number and spread of stars in the sun's neighborhood, the researchers found that other stars would pass reasonably close by the sun every 1 to 2 million years. That means that the sun has probably had between 10,000 to 50,000 close encounters over its lifetime.

And any one of these could easily have caused the sun to gain or lose comets, the simulations suggest. The researchers calculated that at least 5 percent of the Oort cloud comets are likely to be adopted from other stars, though the true figure could be much higher.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

And the encounters were probably two-way transactions; just as the sun may have gained new comets, it just as likely lost some of its own.

"I might not be able to say we have increased the size of the Oort cloud, but we have probably exchanged material at least, so that some fraction of what's in our cloud probably did come from something else," Levine said.

Testing this hypothesis could be difficult, though, the scientists cautioned. For one thing, we cannot be sure other stars even have Oort clouds of their own, as tiny comets would be too dim to detect around any star but the sun. However, Levine said there's no reason to believe our sun is unique in this trait.

Furthermore, it could prove tough to identify any particular comets around the sun that may have originated elsewhere. One possibility is to study the chemical composition of the sun's comets to see if they match that of the sun. If not, they may have formed around other stars with different chemical abundances.

The researchers said the general idea that some of the Oort cloud members may be interlopers does make sense. For one thing, the sun seems to have more comets in its Oort cloud than were predicted based on calculations of how much mass was thought to originate in the sun's close environs when it was forming.

Gosmeyer presented the findings in a poster at the 219th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Austin, Texas in January.

You can follow SPACE.com assistant managing editor Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.