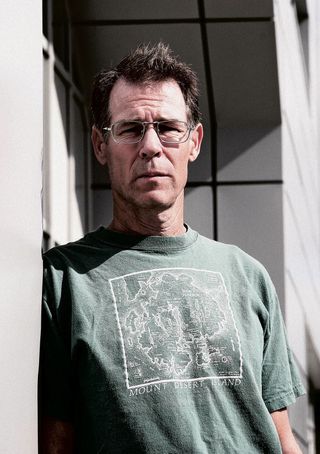

The Future in 2312: Q&A With Author Kim Stanley Robinson - Part 2

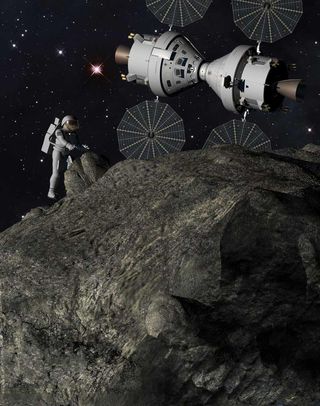

Science fiction author Kim Stanley Robinson envisions a future where humanity has colonized the solar system, and radically transformed gender, longevity and human political systems in the process. This scenario is the backdrop of his new novel "2312," out May 22 from Orbit Books.

In Part 1 of our two-part interview with Robinson, we discuss the hows and whys of terraforming planets, moons and asteroids. Here in Part 2, the writer tells SPACE.com how he thinks people will structure their societies and modify themselves 300 years from now.

SPACE.com: In the book, many of the colonized asteroids and moons are governed by the Mondragon political system, which uses quantum computers to allocate resources fairly between people. Do you think a future system like that could really work?

Robinson: Well, I do. It's basically a leftist position — that people can cooperate, that there doesn't have to be social injustice, that capitalism is a semi-criminal organization of society. This has been constant throughout my career and won't be a surprise to anybody.

And Mondragon is working very well in the Basque region of Spain. Granted, it's a town of under 100,000 people. But it's been functioning in that alternative economic system for decades now and the people there like it.

Of course, almost everybody you ask says, 'Of course, I believe in social justice. It's a good thing.' But it's hard to imagine how to get there and how it would work.

SPACE.com: The whole book struck me as a really optimistic, hopeful take on the future: We might have to put a lot of trust into computer systems, into society in general, but here's a plausible picture of how this could actually all work out.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Robinson: Well, thank you for that. I agree with you, and I think it's a project that hasn't been tried by science fiction novelists for too long. It's somewhat of a blank spot in our vision of the future. I felt like there was a need for a new look at the medium future, seen in a positive light. Not fully utopian, obviously, but that we have a growing industrial and technological and scientific power, and that when we wield it, if we could wield it, then we could get really a good civilization out of it.

What I wanted to try in the novel was thinking, Could that still be true with Earth completely messed up by climate change? And I'm not sure.

The novel is really a question, instead of an answer. If the Earth is struggling with higher sea levels and under enormous environmental stress, can the human civilization still thrive and prosper because of its enormous scientific power?

SPACE.com: I was surprised that you found a way to present even sea-level rise in an optimistic light. That, yes, the seas will rise and terrible things will happen, but you'll also have this great situation of Manhattan turned into Venice, with beautiful canals and bridges and promenades.

Robinson: I was helped a lot by my teacher, the poet Gary Snyder. He taught at UC Davis, and I took classes from him. One time he was saying to me, "Yeah, there's going to be climate change, but people are resilient and ingenious." And so along with all of the bad things that happen, there isn't going to be just some Mad Max fall into dysfunction, chaos and disorder. I mean, that's possible, but it's not the most likely response.

Because of the slowness of climate change's impacts, we're likely to just keep coping and coping and coping. I think the sea-level rise that I've postulated, while it's radical, it's not impossible at all. If we lose the Greenland ice cap and the western Antarctica icecap, then we're going to see much higher sea levels. And a quarter of the world's population lives within 100 kilometers of the oceans, and so the impact is likely to be quite spectacular.

But people aren't just going to lie down and die, or go down to the farm with their shotguns and become survivalists. That just isn't the way it's going to go. There's likely to be a building surge above the new high-water marks. And you'll get some recapturing of stuff that is in the tidal zone.

I have to emphasize these more as questions rather than answers. When I propose this stuff, I'm not saying, this could happen, I'm saying could this happen?

SPACE.com: Which element of your futuristic vision do you think is the most farfetched, and which do you see as likely to come to pass?

Robinson: I do feel like we'll be pushing out longevity. It could be that the rapid terraformation of Venus is a major stretch (laughs). Even more than building the rolling city on Mercury, Venus is such a cauldron. The sunshield that guards Venus from sunlight, that strikes me as really a difficult engineering feat. I guess the most radical body modifications and the terraforming of Venus are probably the two stretchiest parts of the novel. [How to Terraform Your Own Asteroid]

SPACE.com: The gender situation you describe — where many people are not purely men or women, but a little bit of both — that struck me as both one of the most radical, forward-thinking parts of the book, and also as something very of the moment, tied into lots of issues around gender and sexuality that are going on today. Was that aspect of the book motivated by what's going on now, culturally and politically?

Robinson: Yeah, sure. Here we are in this world, and in northern Europe, in the United States, you have what I at one time called a "semi-post patriarchy." The patriarchy as a legal imposition on women and children has somewhat been legally dismantled, and everybody's supposed to be equal together. I'm a feminist myself, but as a man I feel like I have to be kind of a follower there, and not try to once again patriarchally take over feminism by being too loud about it.

But I've always believed that it's obvious and right, just as a matter of human equality. So there's this human equality movement sweeping the planet that has to do with democracy and also gender equality and an end to patriarchy as a system of repression and exploitation. But the planet isn't entirely covered by western democracies and there's still a really heavy-duty patriarchal strain in Islam and in other cultures that are not secular western cultures. So the planet itself is a mess in that regard. [Countries With the Most & Least Gender Equality]

I thought of the novel as a way to symbolize the moment right now. In the United States, who you are is not going to be as determined by your biology. Whereas at the same time on the other side of the planet, who you are biologically is going to slot you into whether you're even literate or not.

I guess the novel is one way of throwing this all in people's faces, and saying, "Why do you link your character traits to your biology? Masculine and feminine, what does that mean compared to male and female? Can they be reversed, can they be confused?"

SPACE.com: It comes back again to this issue of optimism. Do you think a more progressive attitude toward these things is just inevitable?

Robinson: I think it is inevitable. I think it's going to happen.

The more educated people become, the more everybody thinks, "Well, I'm as good as everybody else." And they're right. So any sense of subservience or that there's people who deserve more in this world than I deserve, I think that's going to go away.

Once again, that is somewhat of a guess or a utopian wish. You need maybe the 300 years. The important thing is not to get discouraged when you realize it's not going to be completely solved in your lifetime. That's not the point to give up.

You can follow SPACE.com assistant managing editor Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.