Final Nail? Faster-Than-Light Neutrinos Aren't, Scientists Conclude

The final nail in the coffin may have been dealt to the idea that neutrino particles can travel faster than light.

The same lab that first reported the shocking results last September, which could have upended much of modern physics, has now reported that the subatomic particles called neutrinos "respect the cosmic speed limit," or the speed of light.

Physicist Sergio Bertolucci, research director at Switzerland's CERN physics lab, presented the results today (June 8) at the 25th International Conference on Neutrino Physics and Astrophysics in Kyoto, Japan.

"Although this result isn't as exciting as some would have liked, it is what we all expected deep down," Bertolucci said in a statement.

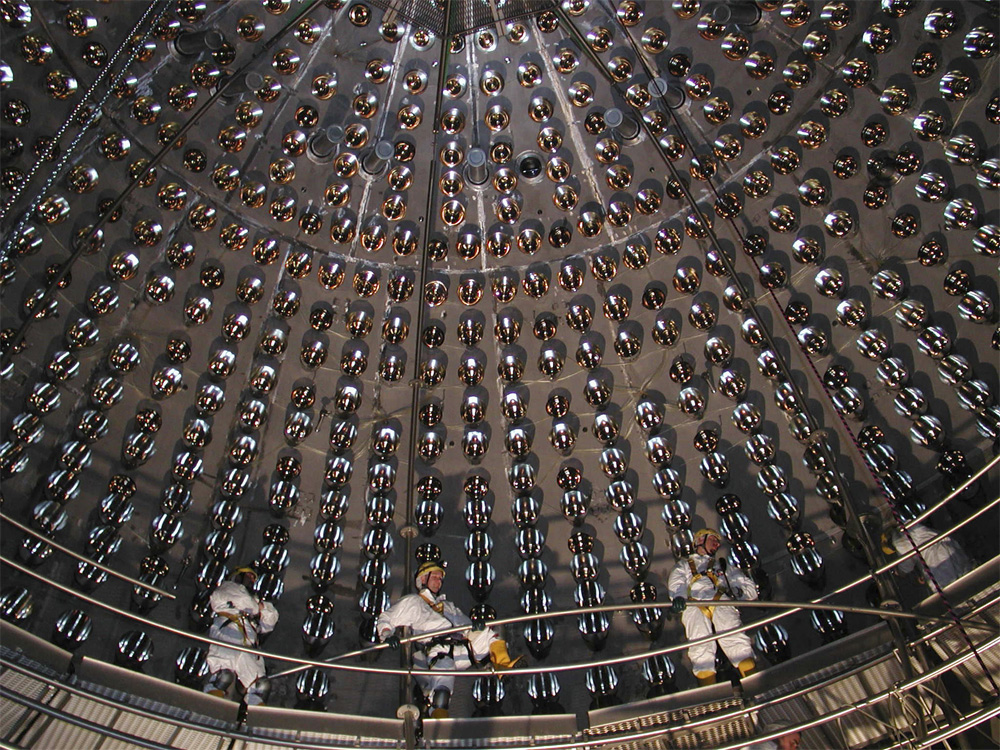

The new findings come from four experiments that study streams of neutrinos sent from CERN in Geneva to the INFN Gran Sasso National Laboratory in Italy. All four, including the experiment behind the first faster-than-light findings, called OPERA, found that this time around, the nearly massless neutrinos traveled quickly, but not that quickly. [10 Implications of Faster-Than-Light Neutrinos]

Last year, OPERA measured that neutrinos were making the 454-mile (730-kilometer) underground trip between the two labs more speedily than light, arriving there 60 nanoseconds earlier than a beam of light would.

At the time, the physicists were stunned because such a result seemed to break Einstein's prediction that nothing could travel faster than light. This idea is at the heart of his theory of special relativity, on which much of our modern technology and scientific understanding is based.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The OPERA researchers weren't sure what could explain their anomalous results, having checked and rechecked their work, so they released their findings to the larger community of physicists in hopes that experts around the world could help them figure it out.

"The story captured the public imagination, and has given people the opportunity to see the scientific method in action — an unexpected result was put up for scrutiny, thoroughly investigated and resolved in part thanks to collaboration between normally competing experiments," Bertolucci said. "That's how science moves forward."

Labs around the world, including the other experiments at Gran Sasso — called Borexino, ICARUS and LVD — as well as the MINOS experiment in Illinois and the T2K project in Japan, tried to recreate the OPERA findings. None were able to do so: Every time, neutrinos appeared to obey the speed limit of light.

Now, the OPERA scientists think their original measurement can be written off as owing to a faulty element of the experiment’s fiber-optic timing system.

This article was provided by LiveScience.com, a sister site of SPACE.com. Follow Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.