NASA's Voyager 1 Probe Poised to Leave Solar System

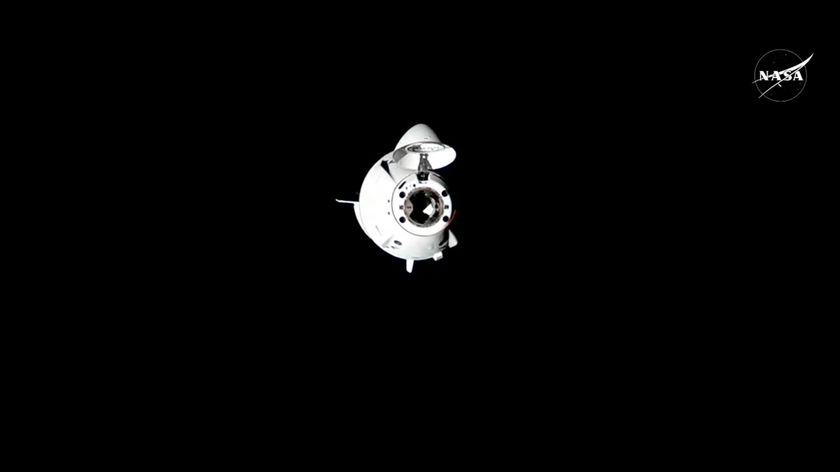

A NASA space probe launched in 1977 is about to become the first manmade object to travel beyond the solar system, scientists report.

The Voyager 1 probe, a relic of the beginning of the Space Age, is still alive and kicking, and due to make history any day now. It's hard to tell exactly where the edge of the solar system lies, but scientists say Voyager 1 is measuring clues that suggest it's close.

"The latest data from Voyager 1 indicate that we are clearly in a new region where things are changing quickly," Ed Stone, Voyager project scientist at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, said in a statement. "This is very exciting. We are approaching the solar system's final frontier."

Voyager 1 is one of a pair of spacecraft launched in 1977. Its twin, Voyager 2, is not far behind it. Voyager 1 is roughly 11.1 billion miles (17.8 billion kilometers) from Earth, while its sibling is currently 9.1 billion miles (14.7 billion km) away from its home planet. [Photos From NASA's Voyager Probes]

"When the Voyagers launched in 1977, the Space Age was all of 20 years old," Stone said. "Many of us on the team dreamed of reaching interstellar space, but we really had no way of knowing how long a journey it would be — or if these two vehicles that we invested so much time and energy in would operate long enough to reach it. "

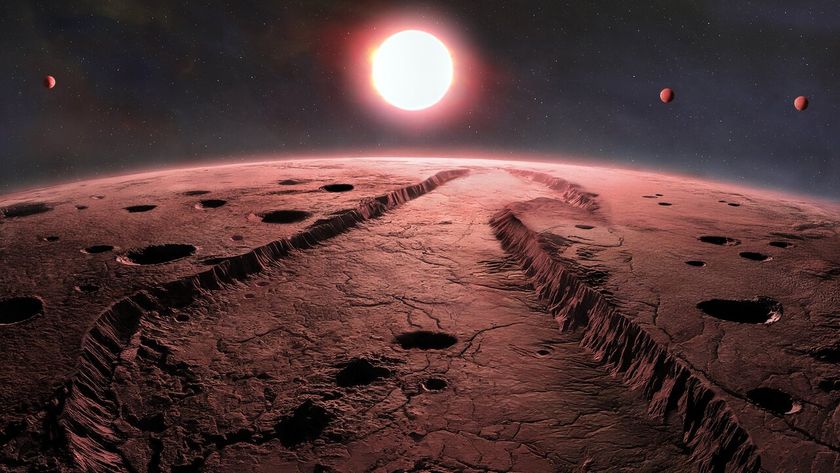

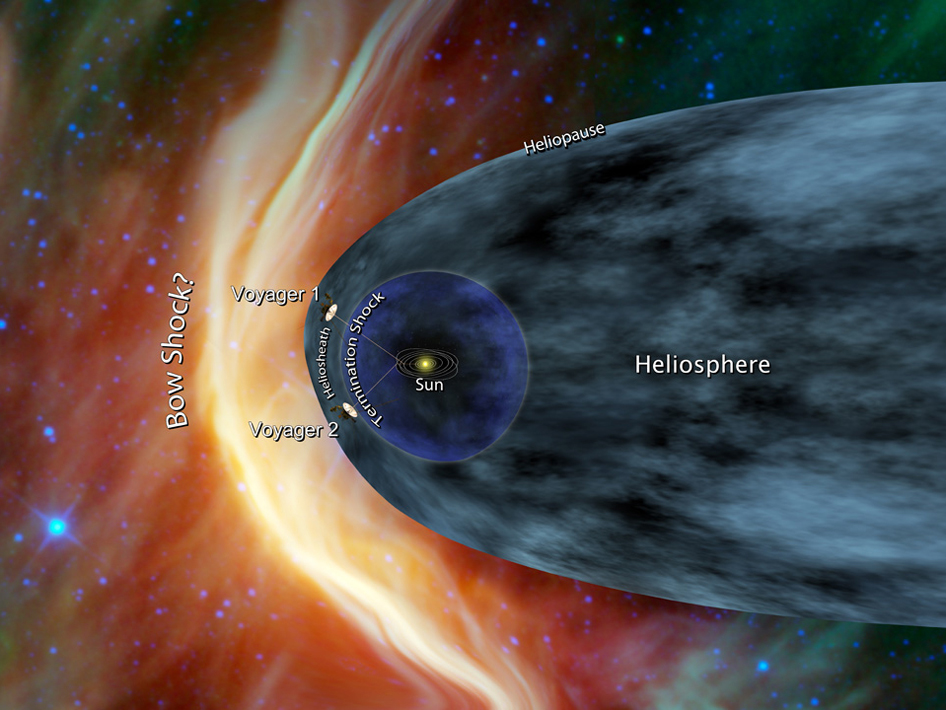

The solar system is bounded by the edge of the heliosphere, the giant magnetic bubble formed by the sun's magnetic field carried into space by charged particles called the solar wind. Outside this bubble is interstellar space.

One sign that Voyager 1 is nearing the edge of the heliosphere is that this bubble has stopped shielding the spacecraft as well as it has from cosmic rays — incoming high-energy particles accelerated through space from distant black holes and supernova explosions. The heliosphere blocks the majority of these from entering the solar system, but Voyager has been encountering more and more cosmic rays as it travels farther, suggesting it is nearing the end of the heliosphere's protection.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"From January 2009 to January 2012, there had been a gradual increase of about 25 percent in the amount of galactic cosmic rays Voyager was encountering," Stone said. "More recently, however, we have seen a very rapid escalation in that part of the energy spectrum. Beginning on May 7, 2012, the cosmic ray hits have increased five percent in a week and nine percent in a month."

This sharp increase in the number of cosmic rays hitting Voyager 1 could mean the probe is nearing the end of the solar system. However, when it does finally cross over, scientists expect a few other signals to herald the moment.

For example, Voyager 1 should notice a lack of the energetic solar particles that filled the heliosphere. The probe should also measure a change in the direction of the magnetic field around it, marking the transition from the sun-directed magnetic field to a new one permeating interstellar space.

Neither of these milestones has yet been seen, but researchers suspect they are not far off.

Follow Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.